When 16-year-old orphan Sarah Downes ran away from home in search of a better life, she moved around the country before finding working as a maid at a farmhouse. Here, she was mistreated and starved giving her no option but to leave and turn to sex work to survive.

When 24-year-old Ann Mountain’s husband and children died, instead of facing the harrowing conditions of the workhouse where she had been sent as a child, she started a relationship with a tailor but it wasn’t long before she contracted ‘venereal disease’ from him and he left her destitute, fighting to make ends meet.

When 25-year-old Ruth Plym visited a doctor’s surgery with a hand injury, she was ‘seduced’ by the assistant and left pregnant. Distraught and alone, Ruth planned to drown herself in Hyde Park but attracted the attention of a passer-by who feigned concern before raping her and giving her syphilis.

Struggling with lives of famine and destitution, Sarah, Ann and Ruth all became inmates at the London Lock Asylum – a charity established in 1787 to house and ‘reform’ female patients who had been “cured” of venereal disease at the nearby Lock Hospital. Founded by a group of evangelical philanthropists and clergy, the Asylum offered women a refuge when the alternative was often sex work.

A key finding

The stories of these women and thousands like them had been lost to time. Too marginalised and maligned to be remembered by the history books. Their stories too tragic but also deemed too unexceptional to be given significance.

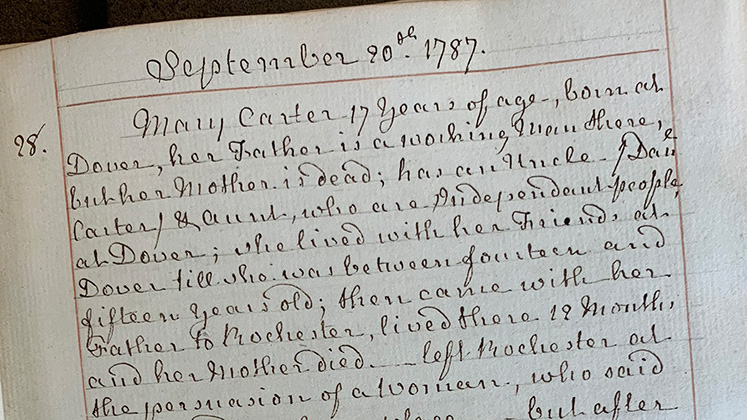

That is, until summer 2019 when Professor Patrick Wallis – while searching the London Metropolitan archive for a historical source he could work on with students – stumbled across a handwritten register describing the lives of over 200 patients at the Lock Asylum during the 1780s and 1790s.

Due to the way it had been catalogued, the document had never been discovered by a historical researcher before. Patrick had found an original source that would take his students to the very heart of historical research and finally bring the lives of these forgotten and neglected women to light.

“The register is a novel way to learn about women in the late eighteenth century who were living very marginalised lives. Many had experienced abuse and worked as prostitutes,” says Patrick. “It’s a population you don’t hear about even though as historians there’s been a long tradition of trying to recover the voices and lives of people who are too marginal to leave their own words.”

Unlocking history

For Patrick, many of the accounts in the register are heart-wrenching but it’s the sheer volume and repetition of them he finds astounding. “For me it’s the layering of this. There’s story after story, girl after girl who has been abused and turned to prostitution. When looking at the register with students, we ask them to think about the shared experiences that link these women so they can see the patterns of pressure and risk they must have been under.”

The register is being used as a teaching tool by Patrick and his colleagues in the Economic History department at LSE and while most students are fascinated by the project, a handful have been surprised by the source – it’s certainly not your standard economic text.

However, Patrick believes the type of social and cultural history the register embodies is integral to learning about economic history. “We need students to think about the economic past in all its dimensions – the register is a way to think about questions of social mobility, inequality, irregular work, the black market and types of economic activity that standard sources don’t tell you about,” he says.

Students have been working as transcribers, deciphering the handwritten entries on the register and researching the women named.

Third year Economic History student Kiera Glendenning was introduced to the project last year. “Being able to work with primary sources that have never been studied so early on in my university career really helped me to understand what the process of historical research entails. While a lot of hours must be put into a research project such as this, when you come across something particularly exciting or interesting it makes the whole process worth it. For example, when I managed to locate the register of baptism for one of the women,” she says.

From page to stage

Kiera also took part in a workshop on the project run by playwrights Cara Jennings and Sophie Trott, where students learnt acting techniques and improvised scenes in the Asylum, using the register entries as prompts to bring the stories of the women to life.

Cara and Sophie will be holding more workshops on the project in December 2020, this time with members of the public.

“We’ve chosen ten women from the Asylum and have written character descriptions for them, reading between the lines of the ledger to decipher what they might have been like as individuals and the relationships between them. We’re really interested in how we can tell the stories of people whose histories have been completely wiped out” explains Cara.

Eventually, Sophie and Cara hope to write a play about the Asylum and believe we can learn from the women today. “There are lots of connections we can draw between the women’s experiences and modern life. For example, the notion of coming to London for a better life and what that might look like in reality,” says Sophie. “There’s also the fact these women were suffering with a disease that no-one understood!” adds Cara.

The voices of these marginalised and mistreated women may have been lost throughout time but Patrick’s serendipitous find – and the work of everyone involved in the project – means they can now finally be heard.

This post is a reblog of an article first posted by LSE News in November 2020. You can read the original article here: Unlocking the past: The LSE project shining a light on the lives of women forgotten by history