John Doukas argues that Germany has been the only country in the European Union which benefitted from the introduction of the Euro. In countries such as Greece and Spain the adoption of the Euro only fuelled excessive debt-making due to lower interest rates on government bonds, he believes.

John Doukas argues that Germany has been the only country in the European Union which benefitted from the introduction of the Euro. In countries such as Greece and Spain the adoption of the Euro only fuelled excessive debt-making due to lower interest rates on government bonds, he believes.

The Euro zone crisis and the uncertainty about the fate of the Euro have been linked to the massive external debts of the EU’s peripheral member countries that, for many, have become unmanageable. However, we should acknowledge that the debt crisis in the Euro zone periphery is not uniform; it did not stem from the same causes. Specifically, while Greece and Portugal have been victims of multi-year government spending profligacy, the roots of the debt crises in Ireland and Spain, can be found in consumer over-spending and the housing bubble, thanks to reckless credit availability. In other words, the debt crisis in Ireland and Spain seems to be a close relative of the U.S debt crisis.

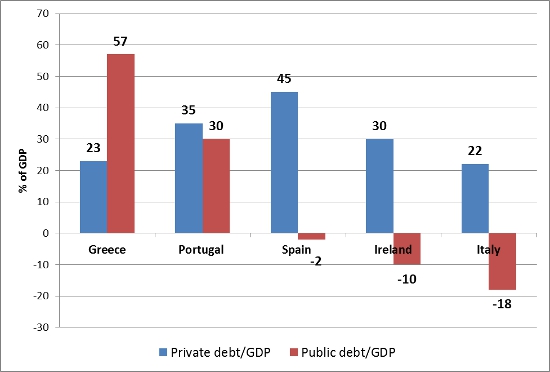

Figure 1 – GIIPS aggregate net borrowing by public vs. private sector: 1999-2007

As Figure 1 above illustrates, net borrowing by the Greek government (i.e., public sector) during the 1999-2007 period, before the crisis, was 57% of GDP, for Portugal 30% of GDP, while for Spain and Ireland the government net borrowing was -2% of GDP and -10% of GDP, respectively. Spain and Ireland were net creditors. Italy also was a net creditor with -18% of GDP net borrowing. By 2009, however, the net external debt of Greece and Portugal went through the roof. Net external debt for Greece reached 78.9% of GDP and for Portugal 77.4% of GDP. On the other hand, Spain and Italy in 2009 had a net external debt of 47.3% of GDP and 42.9% of GDP, respectively, similar to that of 48.5% of GDP for Germany. What is interesting here to note is that the public sector net external debt of countries like Spain and Italy, skyrocketed in a very short span of time (2007-2009). Similarly, the Irish public sector external debt during the 2007-2009 period increased from -10% of GDP to 70.6% of GDP. In other words, the bail out of banks led to a huge external public sector debts. To put it differently, the government (taxpayers) took over the role of the debtor.

If you add the public and private sectors’ net borrowing of a country you roughly end up with its current account balance. When we combine, then, the above numbers for the public sector with the net borrowing of the private sector of these Euro zone countries, we wind up with huge current account deficits, especially for countries like Greece and Portugal. The current account deficit for Greece, Italy, Ireland, Spain and Portugal (GIIPS), deteriorated from -2% to -8% over the 2002 to 2008 period while Germany (with a GDP roughly similar to that of GIIPS), for same period, ran up a 8% current account surplus, approximately offsetting the deficit of the GIIPS. The gap between Germany and GIIPS in 2000 was about 3%. Germany’s current account surplus in 2000 was only 1%. In other words Germany, which did not benefit from the drop of interest rates as much as the GIIPS did with the introduction of Euro (i.e., EU interest rate convergence), managed to increase its current account surplus considerably while the GIIPS experienced large current account deficits.

One can ask the question: how did it happen? A plausible explanation for this phenomenon is that Germany moved out of a hard currency, the German mark, to adopt a weaker currency, the Euro, which, in turn, led to an increased demand of its exports within the Euro zone and the rest of the world. In essence, the adoption of the Euro by Germany had the effects of a depreciating currency while for the GIIPS the effects of an appreciating currency. That is, Germany experienced a depreciating real exchange rate (the ratio of domestic to foreign prices), while the GIIPS countries experienced an appreciating real exchange rate by adopting the euro. This, in turn, induced a current account deficit for the GIIPS financed by capital inflows (net borrowing) which led to their external debt burden. Germany, on the other hand, with a rising current account surplus became a net creditor country. In brief, Germany is, perhaps, the only EU country that benefitted the most from the adoption of the Euro (i.e., a weaker currency relative to the German mark).

Even after the sizable recent haircut of the Greek debt, the external debt of Greece today remains as high as 167% of GDP with an unemployment rate of more than 20%. However, if foreign capital flows had flown mainly into productivity-increasing investments in periphery countries of the Euro zone all these years, such as direct investment by German or other firms, they would have fuelled growth and act as a competitive stimulus which could have allowed these countries to service their capital inflows. The German austerity plan, however, that has been offered as medicine to heal the high external debt problems makes things worse as it deepens the state of economic distress and social cohesion in these countries. At the end, with continuing low economic activity and higher rates of unemployment across Europe, governments with heavy debt burdens may resort to their national currencies, viewed as an alternative structural policy, to undo the failures of the austerity policy adopted since 2008.

The above explanation for the current account imbalance between Germany and the GIIPS may have been amplified by the so-called “trickle-down consumption” phenomenon which seems to result from the desire of GIIPS countries (non-rich consumers) to keep up with Germany and other northern EU members (rich consumers). This argument requires that the GIIPS governments serve as a willing accomplice in the absence of growth strategies to enhance their international competitiveness, which is rather difficult to deny given the degree of political malfeasance in these countries. Politicians, under pressure to respond to chronic structural macroeconomic problems (unemployment, low foreign investment and stagnant wages) in GIIPS and unable to devise growth strategies to boost their citizens’ incomes welcomed the euro as a vehicle that would allow them to achieve economic prosperity through interest rate integration with the rest of Europe (much lower interest rates after to the introduction of the euro) which opened the flood of cheap credit and the purchase of foreign goods and services. In the absence of economic policies with high growth potential for the GIIPS this short-lived prosperity proved to be catastrophic for these economies something that neither governments nor EU policy-makers ever thought it could happen when they were signing the Stability and Growth Pact/Maastricht Treaty. In fact, the Maastricht Treaty focused exclusively on government debt and deficit ratios while they ignored the problem of excessive external debt ratios in the Euro zone that led to a crisis in the financial markets and macro-economy.

While policy-makers can be held responsible for the current account imbalances within the Euro zone, the most important question that has not been answered yet is why the ECB tolerated oversized current account deficits which financed the increasing public and private consumption or bad investments and real estate bubbles? Alternatively, why the ECB put up with excessive external debt ratios in the Euro zone? In other words, the ECB and other Euro zone institutions have done very little to address the rising current account imbalances. The inertia of ECB and other EU policy-makers suggests that they underestimated the dangers of current account imbalances within the EU currency union. This, in turn, facilitated the wage-price increases in GIIPS which further undermined their competitiveness before the crisis and made the improvement in their current account balances unattainable causing the external debt burden to rise to extremely high levels.

Disproportionate and long-lasting external deficits, however, are an existential threat to a currency union which is analogous to a fixed-exchange rate regime. The latter was abandoned by most western countries in 1971-1973 in favor of the floating exchange rate system and in recent years it has been strongly recommended to China to mitigate its current trade imbalances with the west and, particularly, the U.S. It is rather difficult to believe that the EU monetary authorities were unaware of what led to the abandoning of the Bretton Woods (i.e., fixed-exchange rate) system. It seems that the ECB and other EU policy-makers thought that the interest rate convergence after the introduction of the euro would automatically reduce the economic disparities among member countries and produce greater economic prosperity in the Euro zone. Quite the opposite, the Euro zone has failed to carry out policies to secure (i) economic integration and (ii) high levels of economic prosperity. The economic disparities among country members remain more diverse today than ever to the point that they threaten the existence of the euro and the integration prospects of the Euro zone.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/K7ZFnW

_________________________________________

John Doukas – Old Dominion University, Virginia

John Doukas – Old Dominion University, Virginia

John Doukas is the founding and managing editor of European Financial Management (EFM), the leading journal in European finance. He is also the founder of the European Financial Management Association (EFMA). He is the William B. Spong Jr. Chair in Finance and Eminent Scholar at Old Dominion University, Virginia (United States). He is also an Associate of the Judge Business School at the University of Cambridge (United Kingdom). He earned his Ph.D. in Financial Economics at Stern School of Business, New York University.