Using recent survey data, Michael Courtney illustrates that Irish MPs exhibit significantly higher levels of support for European integration than their voters, particularly those in the governing Fine Gael-Labour coalition. This may be due to the disproportionately low levels of female MPs, young MPs and those from lower social classes. However, despite this gap between the preferences of voters and MPs, Ireland’s use of direct democracy on questions of EU integration mitigates any potential democratic deficit.

Using recent survey data, Michael Courtney illustrates that Irish MPs exhibit significantly higher levels of support for European integration than their voters, particularly those in the governing Fine Gael-Labour coalition. This may be due to the disproportionately low levels of female MPs, young MPs and those from lower social classes. However, despite this gap between the preferences of voters and MPs, Ireland’s use of direct democracy on questions of EU integration mitigates any potential democratic deficit.

Irish voters and MPs are in favour of further EU integration, but MPs are much more strongly in favour. How can we explain the attitudinal distance between Irish voters and MPs, and how do attitudes vary within parties at the national level?

Thinking of parliaments in terms of their representative function rather than their legislative function would lead to the reasonable assumption that, in order for a parliament to truly reflect the diversity of opinions in society, the distribution of representatives’ preferences for any given issue should match the distribution of citizens’ preferences. With this in mind, and using data from national surveys in Ireland, I have examined whether there is a “democratic deficit” between voters and MPs when it comes to support for further EU integration, and whether any perceived incongruence is driven by the social elitism of parliament.

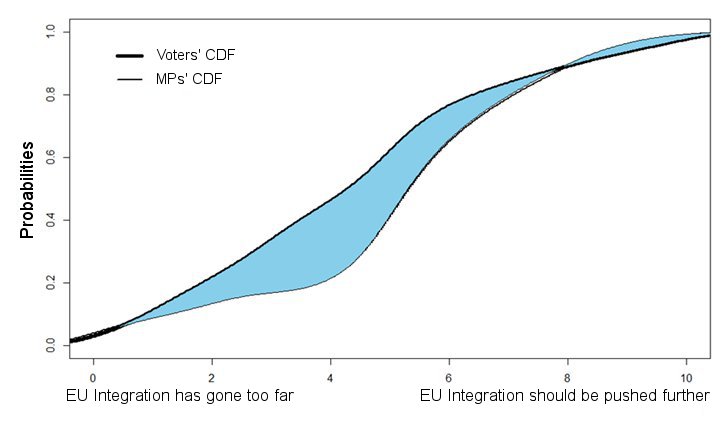

The figure below displays the cumulative distribution functions for Irish voters’ and MPs’ responses to a survey question with a 0-10 response scale measuring support for further EU integration. The surveys were the Irish National Election Study 2011 and the Comparative Candidate Survey (Ireland 2011) (CCS). Those defined as MPs in the CCS are respondents who won a seat in the general election, as opposed to outgoing MPs or other losing candidates.

Probability functions for Irish Voters and MPs’ attitudes to European integration

Looking at the figure, we can see that on the whole, Irish voters and MPs are in favour of further EU integration. But MPs are much more strongly in favour! The probability that a voter will choose a score on the “EU Integration has gone too far” end of the scale is much higher than for that of MPs. The probability of thinking EU integration has gone slightly too far (4 on the scale) is 45 per cent for a random voter, while a MPs’ probability of doing so is merely 18 per cent. The totality of this divergence is represented by the shaded blue area.

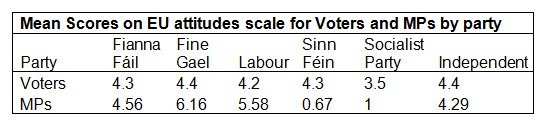

The first step in explaining this divergence of opinion between the groups is to look at the institutional relationship in terms of party affiliation. The table below shows the mean scores for voters and MPs by party affiliation. This concept is defined for voters by the party they gave their first preference to in the 2011 general election.

What the table clearly shows is that on a party basis, the incongruence observed in the graph is being driven by the deviation of Fine Gael and Labour MPs’ preferences for further EU integration from the more hesitant preferences of their own voters. The fact that these parties make up the governing coalition and between them hold 75 per cent of seats in the parliament makes this contrast particularly stark. Although there is also some significant deviation of Sinn Féin and Socialist party MPs from their voters, the percentage of seats they hold in parliament (8 per cent and 3 per cent respectively) is relatively small.

Why then are Fine Gael and Labour so incongruent with their own voters? My primary explanation for the observed incongruence is that the distribution of social characteristics among voters is much wider than that among MPs. This social elitism of parliamentarians is common across most countries. Irish MPs are more likely to be male, middle-class, middle aged and more highly educated than voters. So much so that none of the 20 Fianna Fáil MPs to survive the party’s 52-seat drop in 2011 were women. The general hypothesis is that MPs drawn from over-represented social groups will be in favour of more EU integration. Conversely we should see that female, young, lower class and less educated MPs should be less in favour of EU integration. The between-party and within-party variance was captured using a random-effects multilevel regression model.

The results show that across the parliament as a whole, those in the over-represented ‘AB’ social class are much more in favour of further European integration compared to those in the lower and less well-represented C1, C2 and D classes. While there is no fixed effect of gender across all MPs, female MPs in Fine Gael, the larger governing party with 46 per cent of the seats, are less enthusiastic about further integration than their male party colleagues. The same is true for younger MPs within this party. The implication of this finding is that if the distribution of social characteristics within the parliament better reflected the distribution of those characteristics among voters, it is more likely that there would be better congruence between voters and MPs attitudes. Consequently this would mean less parliamentary support for further European integration.

In terms of the core question, does this divergence of attitudes between voters and MPs constitute a democratic deficit of political representation? Are voters’ views insufficiently represented in the Irish political system due to the social elitism of parliament? Were this to be the case it would provide some justification for pro-active measures to diversify the social representativeness of the Irish parliament such as the recently adopted gender quotas for political parties.

Alas, the answer is no! The divergence between MPs and voters on the issue of EU integration, in isolation, is not a problem for representative democracy in Ireland. Voters must be given the opportunity to vote on any major changes to Ireland’s relationship with the EU through a referendum. As the voter will get the final say, an individual MP’s attitude to Europe is less likely to be an election issue. MPs are then held to account for issues in which the parliament makes final decisions, with EU policy relegated to an afterthought at election time. Contrast this with the UK where candidates’ EU attitudes are heavily scrutinised by the media, as general elections there are usually the only time that voters will get an opportunity to have their say on integration issues, thus incentivising parties to adopt stances that more accurately reflect voters’ opinions.

Should the deliberative democracy element ever be removed from the process of EU integration in Ireland, it would certainly be expected that candidates with a greater diversity of opinion on EU integration would be elected, or incumbents would indulge in a strategic re-evaluation of their attitudes to Europe.

Acknowledgments

This paper uses data from the 2011 Irish Election Study, directed by Michael Marsh (Trinity College Dublin). The article also uses data from the Irish Comparative Candidate Survey 2011, directed by Michael Marsh and Gail McElroy, and administered by Michael Courtney (all of Trinity College Dublin) as part of the Comparative Candidate Survey directed by Hermann Schmitt, MZES of the University of Mannheim, Germany. All data are used with permission of the study directors.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/MB4dAR

_________________________________________

Michael Courtney is an IRCHSS PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science, Trinity College Dublin. His research examines the impact of Irish MPs’ social backgrounds on their political attitudes. He has contributed to two books; How Ireland Voted 2011 edited by Michael Gallagher and Michael Marsh and published by Palgrave MacMillan and Next Generation Ireland edited by Ed Burke and Ronan Lyons and published by Blackhall. He holds a degree in Economics, Politics and Law from Dublin City University.

Michael Courtney is an IRCHSS PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science, Trinity College Dublin. His research examines the impact of Irish MPs’ social backgrounds on their political attitudes. He has contributed to two books; How Ireland Voted 2011 edited by Michael Gallagher and Michael Marsh and published by Palgrave MacMillan and Next Generation Ireland edited by Ed Burke and Ronan Lyons and published by Blackhall. He holds a degree in Economics, Politics and Law from Dublin City University.