Austria went to the polls on 29 September after a major political scandal led to the fall of the previous government. The centre-right ÖVP, led by Sebastian Kurz, won the election and further increased their vote share. Jakob-Moritz Eberl, Eva Zeglovits and Hubert Sickinger write that despite securing a clear victory, the election saw the ÖVP’s campaign engine stutter for the first time since Kurz took over the party leadership. In the end, however, none of the country’s opposition parties could generate enough momentum to mount a serious challenge.

Austria’s last parliamentary election in October 2017 resulted in a clear shift rightward with the centre-right People’s Party (ÖVP) and the far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ) forming a coalition for the third time in Austria’s history. The ÖVP’s election win was foremost attributed to the new leadership of Sebastian Kurz. In addition, the 2017 election was the first parliamentary election after the refugee movements of 2015. Both the ÖVP and the FPÖ managed to profit from immigration being the most salient political issue as they had focused their campaigns on stricter asylum and migration policies.

It wasn’t long before FPÖ politicians began to make headlines with a series of actions and statements, dubbed radical right ‘Einzelfälle’ (isolated incidents), that at least lacked distance from the National Socialist past of the party and country. International concern was furthermore aroused when Minister of the Interior, Herbert Kickl, illegally ordered a police raid on Austria’s own intelligence service, which is, among other things, charged with monitoring and countering right-wing extremism.

Sebastian Kurz rarely commented on these incidents. Mastering the technique of message control, the strategy was actually quite simple: Kurz did not want to see his image tainted by the controversies and thus disassociated himself from his coalition partners whenever necessary.

Prelude to the campaign: The Ibiza scandal and the fall of a Chancellor

On 17 May, the release of a seven-minute long video clip triggered one of the biggest political scandals in Austria’s recent history and marked the beginning of the end of Sebastian Kurz’s first chancellorship. Filmed in July 2017, before the last parliamentary elections, it showed the now Vice-Chancellor and leader of the FPÖ, Heinz-Christian Strache, at a luxury estate on the Spanish island of Ibiza casually trying to convince a woman purporting to be the niece of a Russian oligarch to buy Austria’s largest-circulation newspaper. Benevolent reporting during upcoming election campaigns would then be rewarded with lucrative public contracts once the FPÖ entered government. Internationally, the incident was seen as proof for why centre-right parties should never form a coalition with the far right. Nationally, it created a chain reaction that would bring down the government.

The very next day after the publication of the video clip, Strache resigned and Kurz called snap elections. The latter saw an opportunity to get rid of the FPÖ minister who had attracted the most negative attention in the months leading up to the incident, Herbert Kickl. Blindsided by this move, the resignation of nearly all of the FPÖ’s ministers and the official end of the coalition quickly followed.

Grasping for one last straw, on 22 May, Kurz requested that President Van der Bellen swear-in a group of technocratic experts, carefully selected by him personally, to replace the former FPÖ ministers and form an interim ÖVP minority government. The relief was brief, as merely five days later, the Social Democrats (SPÖ), the FPÖ and the green splinter party JETZT (formerly List Pilz) succeeded with a vote of no confidence. This had never happened before in Austria, and left the public astonished. ÖVP officials were outraged, while the opposition parties (with the exception of the liberal NEOS) stated that they were not going to back a minority government when the ÖVP had not even made an attempt to find an agreement with them.

Calmly following the guidelines spelled out in the Austrian constitution, the President (a former leader of the Green party) did not miss the chance to inaugurate the first female Chancellor and thus named Brigitte Bierlein, a judge at the Constitutional Court, the leader of Austria’s first expert government with no partisan affiliation.

Stuttering engines and helpless spectators

While this also meant that Sebastian Kurz had formerly lost his ‘incumbency bonus’, this didn’t keep his campaign from having billboards with the words ‘Austria needs its Chancellor’. However, expectations about Kurz’s capacity to oversee a highly professional election campaign were quickly dampened and it became clear that the 2019 campaign would not run as smoothly as in the previous election.

The weekly news magazine Falter uncovered that a member of Kurz’s team had five hard drives from the Chancellery destroyed and did so under a false name, false address and without paying the bill to the specialist company that carried out the work. The same media outlet also uncovered that a number of millionaires had been donating money to the party, but slicing their donations in such a way that the public wouldn’t immediately find out about them. Yet another set of documents, published only a few weeks before the election, suggested that the ÖVP had intentionally planned to overspend during the 2017 election campaign (the party exceeded the campaign cost limit in 2017 by almost twice the legal amount). They also showed that the ÖVP had major and non-transparent expenditures over the last few years, leading the party into high levels of debt while at the same time it was publicly advocating for austerity.

When it came to the campaign itself, either by coincidence or on purpose, the ÖVP and the FPÖ ended up with quite similar campaign slogans. They both used a variation of ‘one who speaks our language’, a slogan that former Austrian far-right leader Jörg Haider had already been using in the 1990s. Most notably, the main policy focus of the ÖVP’s re-election campaign was once again on immigration. Perhaps surprisingly given the international and domestic criticism received, Kurz consistently stressed that he wanted to ‘continue the path’ of the previous government, and in contrast to other parties, he did not rule out another coalition with the FPÖ.

After the so-called Ibiza-gate and the resignation of their party leader, the FPÖ had to quickly reorganise and decided to opt for a double leadership. On the one hand, former presidential candidate Norbert Hofer was supposed to be the friendly face of the party. His aim was to appeal to voters that might have left for the ÖVP, either since Ibiza or since one of the several ‘Einzelfälle’. He also intended to make it clear that the party was open to another coalition with Kurz. Herbert Kickl, on the other hand, became the ‘bad cop’ of the duo. He openly attacked Kurz for removing him from the government and took a strong anti-immigration stance at campaign events. Similar to previous election campaigns, the FPÖ’s main message was ‘Austria first’. Former party leader Strache, however, continued to haunt the party: only a few days before the election, a new corruption scandal centred on his alleged misuse of party funds made the headlines.

During the eighteen months of the ÖVP-FPÖ government, the then opposition parties, the SPÖ, the liberal party Neos and JETZT, had experienced leadership changes, of which some were more structured than others. While the European elections, held just a few days after publication of the Ibiza video, should have been their moment in the spotlight, none of the parties were able to profit from the scandal nor from the collapse of the coalition later on. Even during the September election, they were mostly helpless spectators.

However, the extra-parliamentary opposition, foremost led by the Greens, who had not managed to achieve parliamentary representation during the last election for the first time in their history, experienced a revival. Among other factors, this was due to the increased public salience of the ‘climate crisis’. Continuously polling above 10% since July, the Greens ran an optimistic election campaign focusing on their ambition to re-enter parliament.

Clear election winners and new possibilities?

As the election grew closer, it became clear that all the aforementioned obstacles in Sebastian Kurz’s campaign for re-election would be largely irrelevant to his voters. In fact, every single poll since June had the ÖVP at least ten percentage points ahead of the second strongest party. The first election forecast on Sunday then confirmed that after being the first Chancellor to have ever been ousted in Austria’s post-war history, he would be the first one to rise back to power.

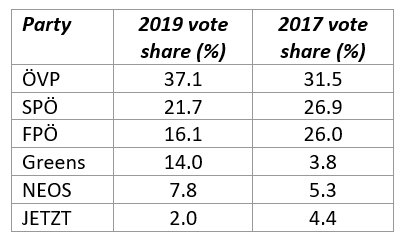

Table: Preliminary election result for the 2019 Austrian election (29 September)

Note: The figures shown in the table are preliminary results derived from a forecast based on 99.6% of the vote. This table will be updated once the final results including absentee ballots are calculated.

Kurz not only rose back to power, he outperformed the other parties by a clear margin. The SPÖ, in turn, will have to face up to the fact that they have not benefited from their role as opposition leader at all. In fact, they had their worst result ever. While at the European elections in May, it seemed as if their scandals would not hurt the FPÖ much, the party was the biggest loser of this election. Conversely, the second clear election winner ended up being the Greens who accomplished an impressive comeback with the best result in their party history. NEOS, while only making small gains, consolidated their status as a permanent addition to the Austrian party system, but this could not be said for the green splinter party JETZT, who lost much of their support.

Looking back, the ousting of the Chancellor may thus have empowered him only more, as not even a controversy riddled campaign gave the opposition parties enough momentum to break the ÖVP-FPÖ majority in parliament. In total the former governing parties have merely lost a combined 4.24 percentage points, which seems indicative of a trend Ruth Wodak previously called ‘shameless normalisation’, where anything goes as long as the main scapegoat still remains, namely the immigrant. Nevertheless, coalition bargaining may still become more complicated than initially expected, as the FPÖ’s electoral losses might dampen their wish for a continuation of a coalition with Kurz. Exit polls also suggest that voters do not show as clear a preference for an ÖVP-FPÖ coalition as they did in 2017.

The fact remains, however, that there is no coalition-option without Kurz as Chancellor and Social Democratic leader Rendi-Wagner has already said that she would be open for a renewal of the ‘Grand Coalition’. Most importantly, however, for the first time since 2003 and for the second time ever, even a coalition between the ÖVP and the Greens would be possible. The coming months will show whether the partially pronounced policy incongruence between the two parties will become an insurmountable coalition obstacle.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: ooevp-at (CC BY-ND 2.0)

Hi, quick question – is a minority government at all a possibility? I can’t think of an example in post-war Austrian history, but you’d think Kurz could negotiate temporary majorities for at least a while, and avoid a second election.

Or would he rather go to the polls again next year in hopes of absorbing more FPO votes?

Hi Ben,

So the last minority gov was by the SPÖ in the early 1970s for 18 months (with support of the FPÖ).

A Kurz minority gov is definitely possible – but unlikely. However, the next weeks are crucial. I would not rule out any option (with FPÖ or SPÖ or GR) at this point.