Austria goes to the polls on 15 October, with the centre-right ÖVP, led by 31-year-old Sebastian Kurz, currently ahead in the polls. Jakob-Moritz Eberl, Eva Zeglovits and Hubert Sickinger provide a comprehensive preview of the vote, writing that although polling is consistent with the idea the ÖVP and Kurz are the probable election winners, a noteworthy number of voters are still undecided. Kurz becoming the next chancellor is thus not as set in stone as Angela Merkel’s win in Germany was.

Austria goes to the polls on 15 October, with the centre-right ÖVP, led by 31-year-old Sebastian Kurz, currently ahead in the polls. Jakob-Moritz Eberl, Eva Zeglovits and Hubert Sickinger provide a comprehensive preview of the vote, writing that although polling is consistent with the idea the ÖVP and Kurz are the probable election winners, a noteworthy number of voters are still undecided. Kurz becoming the next chancellor is thus not as set in stone as Angela Merkel’s win in Germany was.

Credit: Michael Tholen (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Austria’s last parliamentary election in September 2013 resulted in two new parties gaining parliamentary representation, the populist Team Stronach (founded by billionaire Frank Stronach) and the liberal NEOS, while the BZÖ, Jörg Haider’s party which was in government between 2002 and 2006, failed to pass the threshold for parliamentary representation. The governing parties, the Social Democrats (SPÖ) and the People’s Party (ÖVP), recorded all-time lows in support, but still formed a coalition after the election. Team Stronach, however, deteriorated into insignificance very soon afterwards.

Since then, however, Austrian voters have become increasingly dissatisfied with the performance of the SPÖ-ÖVP government. Eventually, the so-called refugee crisis in 2015 led to the right-wing populist FPÖ surging into first place in the polls. Soon after, in 2016, both government parties suffered a heavy defeat in the presidential elections, when their candidates gained only around 10% of the vote each, and failed to participate in the second, decisive round of the contest. This second round took place after an election annulment, a postponement and a campaign that spanned nearly a year. Finally, Alexander van der Bellen, a former Green politician, was elected president, while many Austrians were still left in doubt over the integrity or at least the efficiency of their electoral institutions.

Partly due to the embarrassing defeat in the presidential election, discontent with the leadership within the SPÖ rose to such a point that in May 2016 the party’s leader and chancellor Werner Faymann stepped down. A week later, Christian Kern, CEO of the Austrian Federal Railways (ÖBB), was introduced as his successor.

With a new and popular SPÖ leader radiating change, the ÖVP was increasingly put under pressure, eventually disrupting the political climate within the coalition. After strongly criticising his own party’s unwillingness to continue their cooperation with the Social Democrats, vice chancellor and ÖVP leader Reinhold Mitterlehner ultimately resigned in May 2017. Soon after, Sebastian Kurz, the then 30-year old charismatic foreign minister and rising star of the party, took over the ÖVP and called snap elections. In doing so, Kurz put the SPÖ before a fait accompli, demonstrating his strength as a political actor and giving the impression the he was in command of the government.

The early campaign phase – new parties and faces

The ÖVP launched a highly personalised election campaign, with clear populist features. The party decided to focus their communication strategy on the persona of Kurz, with little room for policy statements. Even their party name, which is now formally “Liste Sebastian Kurz – die neue Volkspartei”, reflects this personalisation. In the spirit of emphasising the radical transformation of the party, they also chose a new party-colour (turquoise) and new faces have been placed prominently on the candidate lists; among them former athletes, scientists, celebrities and a high-ranking leader within the police force. Judging by the party’s immediate surge in the polls, shown below, their strategy has clearly worked.

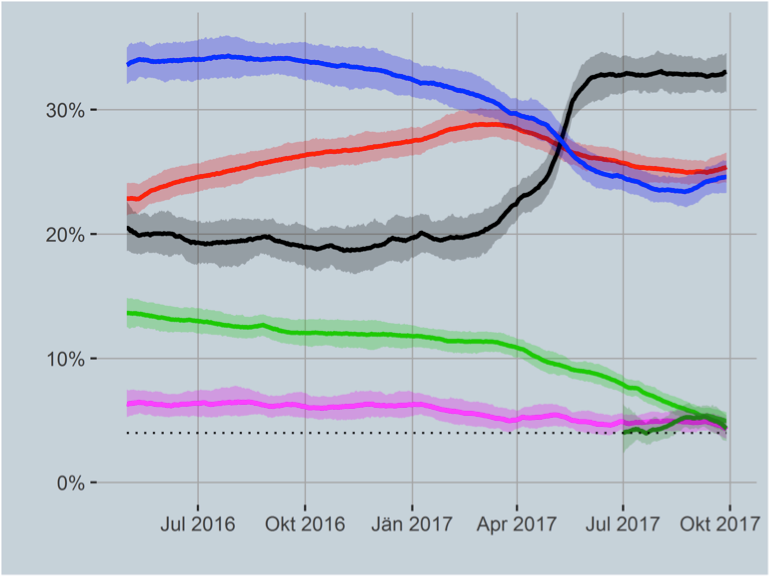

Chart: Aggregation of Austrian opinion polls published since May 2016

Note: Blue = FPÖ, Red = SPÖ, Black = ÖVP, Green = Light Greens, Pink = NEOS, Dark Green = Liste Pilz. Source: Laurenz Ennser-Jedenastik, University of Vienna

In June 2017, the Greens held their 38th party congress. Delegates elected a new party leader (Ingrid Felipe) and leading candidate (Ulrike Lunacek), since their former leader and candidate, Eva Glawischnig, had stepped down just a few weeks earlier. They also kicked-off their campaign and voted on their complete list of candidates for the upcoming election. Little did they know that these internal elections would come to have major consequences.

When Peter Pilz, a Green MP and founding member of the party, lost the contest to be assigned fourth place on the candidate list for the national election, he decided to leave the party altogether and formed his own electoral list, the Liste Peter Pilz. Eventually, other renegade members from the Greens and SPÖ, as well as activists and experts from a variety of fields joined this new list, forming what the media would soon come to call the first left-wing populist party in Austria. For the Greens, this was a major blow and changed their narrative insofar as political observers began to question whether they would be able to pass the electoral threshold of four per cent.

Elsewhere, NEOS, who gained parliamentary representation in 2013 and soon after surged in the polls above 10 per cent, have seen their support stagnate around five per cent during 2017. Only after Irmgard Griss, an independent candidate who made it to third place during the first round of the last presidential election, joined the party in July 2017, did the media and political commentators accept the party’s electoral viability, which until then had appeared in doubt. Meanwhile, the FPÖ was not a major presence in the early campaign, possibly due to their limited resources after a year of backing Norbert Hofer’s ultimately unsuccessful presidential campaign.

The main campaign – everyone against Kurz?

Electoral campaigns in Austria are characterised by a strong focus on posters and ads in newspapers and by a great variety of TV debates (there were 27 scheduled for the 2017 election). TV ads had not been an option for decades due to the monopoly of the public Austrian broadcasting company which lasted until 2000. Although there are several successful private TV stations now, TV ads are still an almost negligible feature of electoral campaigns in the country. However, all parties have finally incorporated social media into their campaigns, and Facebook and YouTube videos have now become a “must have” for all parties. While unofficially some may have prepared much sooner, most parties officially started their campaigns at the end of August or the beginning of September.

Despite their traditional focus on their leader, Heinz-Christian Strache, the FPÖ has also tried to make Norbert Hofer visible in their campaign, with Hofer even taking Strache’s place in one of the TV debates. As he gained many more votes in the presidential campaign than the FPÖ ever did in any previous election, it makes sense to use Hofer’s success to attract voters and in particular ÖVP voters who supported him in the presidential election. However, while the FPÖ may have wished for similar circumstances to the presidential election, it has now lost its unique selling point as the anti-immigrant and anti-establishment party and has instead attempted to make the claim that Kurz has simply stolen their policies and ideas.

Unaware of the upcoming snap elections, the SPÖ had already presented their detailed “Plan A” in January 2017, declaring their position on various policy issues. Most strikingly, the party decided to move toward the right on the issue of immigration as a reaction to increasing support for stricter immigration and asylum policies among the Austrian population and as a response to pressure from the ÖVP and FPÖ.

Overall, the SPÖ campaign has not gone as smoothly as planned. The SPÖ was put on the back foot when their consultant Tal Silberstein was arrested on corruption charges in August. However, weeks after they had parted ways with Silberstein, a new problem arose. It was alleged that Silberstein’s former staff members continued to manage two Facebook groups that were publishing racist and antisemitic content while pretending to be ÖVP and FPÖ pages. Taking responsibility for what had happened while denying any involvement, campaign manager and SPÖ managing director Georg Niedermühlbichler stepped down on 30 September. Although Kern is the incumbent, all of the published polls have shown the SPÖ in second or even third place, which has led to the odd impression that the SPÖ and Kern are the ones who are challenging Kurz and his “new ÖVP”, and not the other way round.

Uncertain outcomes

While it is certain that – with 16 parties on the ballot – this election has the largest selection of competing parties since 1945, most of them will not gain a noteworthy number of votes. Still, we should expect large shifts in the electorate on 15 October.

For the first time, an overwhelming number of contending parties are no longer defining themselves as parties, but instead want to be called lists and movements (inspired by Macron’s campaign in France). Also, for the very first time, there is a real chance that a left-wing populist party, the Liste Peter Pilz, might make it into parliament, thus further diversifying the party-spectrum in Austria. At the same time, the Greens may very well face their biggest electoral defeat at a parliamentary election, just one year after having won the presidency.

Polls over the last few weeks have been consistent with the idea that the ÖVP and Sebastian Kurz are the probable election winners. However, a noteworthy number of voters are still undecided. Kurz becoming the next chancellor is thus not as set in stone as Merkel’s win in Germany was. Voters are anxiously awaiting the results of the SPÖ internal inquiry regarding the two Facebook pages. Kern has even started to suspect the ÖVP of involvement, accusing his political opponents of a false-false-flag operation. Regardless of who is ultimately identified as having pulled the strings, this election will have left an unpleasant aftertaste.

The biggest uncertainty lies, however, in something some may argue to be one of the most important objects of any electoral campaign in a multiparty system, namely, post-electoral government formation. While a right-wing coalition between the ÖVP and FPÖ is likely, both in terms of their predicted seats as well as their overlapping policy agendas, other coalitions are also still in the running. Although Kern has said that he will go into opposition should the SPÖ not secure first place, there is speculation and probably enough leeway for an ÖVP-SPÖ as well as an SPÖ-FPÖ coalition as well. However, a Jamaica-style coalition between the Conservatives, Liberals and Greens, as now envisaged in Germany, is rather unlikely.

Given the new and greater supply of parties and the perceived likelihood of a coalition other than a “grand coalition” emerging from the vote, one can expect a high turnout. With under two weeks to go, the campaign is as enthralling as ever.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Jakob-Moritz Eberl – University of Vienna

Jakob-Moritz Eberl – University of Vienna

Jakob-Moritz Eberl is a Research Fellow in the Department of Communication at the University of Vienna and member of the Austrian National Election Study (AUTNES). He is on Twitter @JaMoEberl

Eva Zeglovits – IFES

Eva Zeglovits – IFES

Eva Zeglovits is managing director of IFES, an opinion polling company in Vienna. She is on Twitter @EvaZeglovits

–

Hubert Sickinger – University of Vienna

Hubert Sickinger – University of Vienna

Hubert Sickinger is a Lecturer in Political Science at the University of Vienna. He is on Twitter @HubertSickinger

Pilz is left wing in economic questions, but he is also fighting against islamisation, something that he has in common with right wring parties.

As an outside observer of Austrian politics I think the piece is generally pretty good and insightful, however I disagree on the qualification of Liste Peter Pilz as “left-wing populist”. At the same time, I consider parts of the SPÖ and the Greens to be left-wing populist.

The key criterion to qualify a party as populist is, for me, giving simple answers to complex questions. Right-wing populism wants to solve all immigration and integration issues by closing the borders, not providing government transfers to migrants and celebrating national culture. Peter Pilz has differentiated takes on issues like humanitarian aid, migration and integration, so he’s not a populist.

Conversely, some parts of SPÖ, specifically in Vienna, as well as the Green Party, do give simple answers to complex questions. They think anyone who wants to live in Europe can come here, you just tax the rich or prevent tax fraud for dozens of billions per year to pay for all of it, and with some tolerance and a smile all integration issues will vanish in thin air.

The common denominator for the authors’ use of the term ‘populist’ seems to be skeptical views vis-à-vis Islam and migration. I think a more basic definition, that focuses less on content and more on rhetorical elements and complexity of policy proposals, or policy-oriented ideas, is more useful.