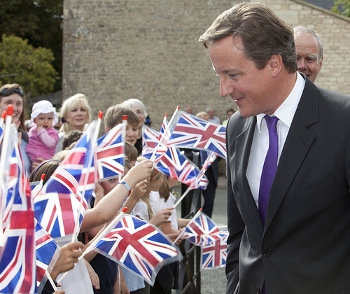

This week sees the annual Conservative Party Conference, the lead up to which has been characterised by strong language from leader and UK Prime Minister David Cameron on the UK’s relationship with the EU. Françoise Boucek argues that Cameron’s management of dissent within his party, by seeking compromise and appeasing opponents, is based on lessons learned from the Conservatives internal rows over Europe during the 1980 and 1990s.

This week sees the annual Conservative Party Conference, the lead up to which has been characterised by strong language from leader and UK Prime Minister David Cameron on the UK’s relationship with the EU. Françoise Boucek argues that Cameron’s management of dissent within his party, by seeking compromise and appeasing opponents, is based on lessons learned from the Conservatives internal rows over Europe during the 1980 and 1990s.

Europe has long been a problem for Britain’s Conservatives. David Cameron has learned the lessons of his predecessors and hopes his diplomatic skills will keep the peace in his party, in his coalition government and in a changing Europe until at least the 2015 general election. Cameron’s recent rhetoric on Europe reflects growing Conservative unease over Europe prompted by rising popularity for the UK Independence Party (UKIP), strains in the coalition government and policy headaches from renewed EU drives for supranational governance.

Going into the Conservatives’ 2012 annual conference, the talk has been about EU budget freezes, British opt-outs and opt-ins, a potential referendum on EU membership and a review of the balance of EU competences. It’s all reminiscent of the Thatcher-Major factional wars over Europe analysed in my forthcoming book Factional Politics: How Dominant Parties Implode or Stabilize (Palgrave).

Last July, Foreign Secretary William Hague launched the Review of the Balance of Competences in the EU described by J. Clive Matthews on this blog as ‘a waste of time’ due to the impossibility of conducting a proper costs/benefits analysis. I attended the audit’s initial workshop a week before the Conservative conference and it looked like this consultation exercise aims to defuse Conservative dissent while kicking the European issue into the long grass.

This workshop didn’t instil much faith in the government’s commitment to the exercise and had all the hallmarks of an internal conversation. Participants were almost all EU stakeholders from the public sector including representatives from EU member state embassies in London, consumer and environmental groups, a handful of academics and one or two from business organisations. Phillip Souta from Business for New Europe joined the four-member panel at the last minute. It certainly didn’t feel like the launch of a constructive Europe-wide debate about reforming the EU to enhance its democratic legitimacy and reconnect with its citizens as touted in the FCO’s Command Paper. Indeed, the FCO panellist left early and gave evasive answers about the audit’s structure, reporting methods and measurements.

Eurosceptic Conservatives have been buoyed with the promise of more ‘veto moments’ from Cameron like last December when he threatened to block a fiscal pact to stabilise the eurozone. In reality, though, it wasn’t a veto opportunity since no new EU-wide treaty was required and the UK isn’t a member of the eurozone anyway. Still, it allowed Cameron to toss a scrap of red meat to Conservative dissidents and a largely eurosceptic populace and to exaggerate his capacity for saying ‘no’. After all, he had just suffered a record post-war legislative rebellion when more than half his caucus supported a motion calling for a referendum on the UK’s EU membership. Cameron’s use of a heavy-handed three-line whip over a non-binding vote was an unnecessary reminder of Conservative divisions in John Major’s years.

These days, the capacity for any EU national government to veto EU policy is limited by treaty changes and EU enlargement. It’s also more difficult to mobilise support and build alliances in an EU of 27 member states than just the nine or 12 from Western Europe during the Thatcher-Major years. Moreover, the opportunities for the UK to strike special deals in the European Council, like the 1984 budget rebate, or the 1992 opt-out of the euro, have just about gone.

Cameron’s management of intra-party dissent is complicated by the constraints of coalition government, where he has to strike a delicate balance with the pro-EU Liberal Democrats led by Nick Clegg, a former MEP. The current audit of the EU’s existing competences was part of the coalition government programme agreed in 2010.

Cameron knows only too well the problems Europe causes for British Conservatives and told them himself upon becoming leader in 2005 that they had to ‘stop banging on about Europe’. In the 1980s, Thatcher polarised party opinion with her strident anti-Europe views and made enemies of former Chancellors of the Exchequer Geoffrey Howe and Nigel Lawson, her once neo-liberal comrades in the battle of ideas.

Thatcher’s successor John Major headed a deeply divided party during the tricky negotiations of the Maastricht Treaty creating monetary union. Against the odds, he won a fourth consecutive victory for the Conservatives in 1992 but with a reduced majority of 21 seats. This increased the leverage of eurosceptic MPs who demanded an EU referendum and their support was critical to the government’s survival as by-election defeats piled up. Major refused to compromise and threats of EU deadlocks and votes of confidence in the government failed to discipline the rebels who were eventually disowned but later readmitted. This mistrust and disunity contributed greatly to the Conservatives’ crushing loss to Tony Blair’s Labour in 1997.

Cameron thinks he’s learned from his predecessors and is comfortable striking compromises and appeasing opponents. Like Blair, he is adept at reframing divisive issues to defuse them. He recently stated that he doesn’t think it is in Britain’s interest to leave the EU but quickly added that British voters would have to give ‘fresh consent’ for any change in the UK’s relationship with the EU. He is also changing the context by focusing on the EU’s 2014-2020 budget negotiations and pushing for a freeze in EU spending in coalition with natural allies in northern Europe.

Françoise Boucek’s book Factional Politics: How Dominant Parties Implode or Stabilize (Palgrave Macmillan) is due out in November 2012.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened url for this post: http://bit.ly/VJpBfS

__________________________________

About the author

Françoise Boucek –School of Politics and International Relation, Queen Mary University of London

Françoise Boucek –School of Politics and International Relation, Queen Mary University of London

Françoise Boucek is a Teaching Fellow in European Politics in the School of Politics and International Relations at Queen Mary, University of London, a Visiting Professor at the University of Witten Herdecke (Germany) and an Associate of the LSE Public Policy Group. A political scientist, she gained her PhD from LSE and researches chiefly on party politics in advanced industrial countries. Her book Factional Politics: How Dominant Parties Implode or Stabilize (Palgrave Macmillan) is due out in November 2012. She is also co-editor (with Matthijs Bogaards) of Dominant Political Parties and Democracy: Concepts, Measures, Cases and Comparisons(London: Routledge, 2010).