Austerity and the impact agenda have led to a rise in campaign groups and think tanks in support of public universities and the social sciences in both the UK and Europe. Anne Corbett examines three recent efforts in this direction, finding a worrying level of insularity in the UK’s organisations. She writes that there is space for a Campaign for European Universities which could strengthen the impact of the bodies involved in academic research.

Austerity and the impact agenda have led to a rise in campaign groups and think tanks in support of public universities and the social sciences in both the UK and Europe. Anne Corbett examines three recent efforts in this direction, finding a worrying level of insularity in the UK’s organisations. She writes that there is space for a Campaign for European Universities which could strengthen the impact of the bodies involved in academic research.

It is the London bus story all over again. You don’t see one for ages, then three come along. Recent weeks have produced three documents which tell us a great deal about the attitudes of universities to Europe and why ‘Europe’ in some form wants them to be more fully engaged.

Craig Calhoun, well known for wide-ranging work on big questions of the social sciences (and, of course, LSE’s new director), chose at least five alluring words for the title of his inaugural lecture: Knowledge Matters: the public mission of research universities. The content on the strategic possibilities for a research intensive institution like LSE was alluring too, especially given its commitment to public policy and high level social sciences. But for a Europeanist it was surprising that his scenario for a leading European university makes no mention of the Europe dimension. Yet the Bologna Process is out there gradually constructing a European Area of Higher Education, and the EU research strategy and ‘knowledge triangle’ of Europe2020 has big implications for institutions. The Calhoun bus however appears to be heading direct to the stop labelled Global.

Then there is the recently launched Council for the Defence of British Universities (CDBU). It has been mocked in the blogs for its pride in claiming its Council includes 16 peers. And blogging registrars complain the CDBU treats them as a servant class and forgets that the 21st century has arrived. Despite these critiques, the CDBU’s strength is that it has been created essentially by public intellectuals and not the usual suspects of organised higher education, which gives it immediate political weight. More fundamentally, the founders are right to proclaim that there has been a vacuum where there should be an arena, for working out how the essential values of the university can be maintained when the political rhetoric is so geared to the economic values of efficiency and productivity.

However, and once again from a European perspective, why should we be so insular? UK Ltd is a limited destination. And above all there is a vacuum on exactly these issues at the European level. Responses to the CDBU from concerned academics and intellectuals from elsewhere in Europe suggest that some will set up parallel organisations. That would have great potential in terms of Europe supporting university values since there is already a political space in which they could act to modify policy agendas.

The Bologna Process has already achieved some breakthroughs in embedding its action lines in principles due to its university and student leadership stakeholders. But principles and values have to struggle in a forum in which there are many different governmental and technocratic players. Now, there is a space for an advocacy Campaign for European Universities which in turn could strengthen the impact of the bodies involved in academic research and scholarship such as the University Association for Contemporary European Studies (UACES).

The third document, released on 4 December, was masterminded by one of Europe’s most charismatic politicians, Jo Ritzen, former Dutch minister of education, recent President of Maastricht University, and creator of the think tank EmpowerEU (EEU) and, maybe, future MEP. The think tank has just launched an ambitious study, The State of University Policy for Progress in Europe. The project has developed indicators which are claimed to empower European universities to contribute better to the European economy – in other words policies which provide universities with appropriate resources and regulatory environments to contribute better to economic innovation. The political punch of the report is that the results are starkly presented in terms of systems (e.g. UK generally high scoring along with small countries, France almost invariably low scoring; and the other large European countries in the middle).

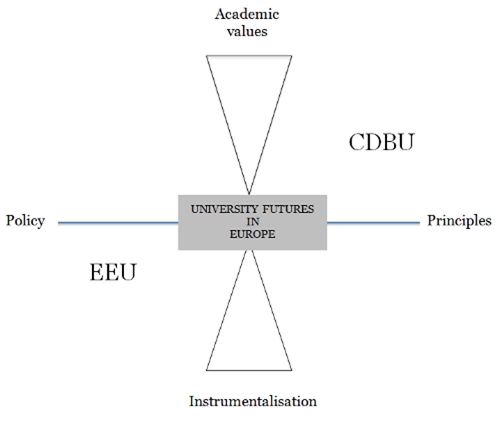

Figure 1 – Campaigns and values

The EEU report needs further study and evaluation. But in terms of university values, the main concern here is whether the EEU’s efforts are at the antipodes of CDBU concerns, as indicated in Figure 1. It is unequivocally instrumentalising the economic contribution of universities and arguing for the reforms of organisation and funding which would enable universities to be more effective in contributing to research and innovation. Yet it shows some understanding of how successful universities work in taking a strong stand against playing national political games with universities.

From a political science perspective I’d say that the differences between these three rather different contributions might be less important than the fact that universities are at the centre of their concerns. The present crisis, with economies in disarray, offers opportunities to make it clear why universities are important to European life.

Anne Corbett has recently had published ‘Principles, problems, politics: what does the historical record of EU cooperation in higher education tell the EHEA generation?’ In: Curaj, Adrian and Scott, Peter and Vlasceanu, Lazăr and Wilson, Lesley, (eds.) European Higher Education at the Crossroads: Between the Bologna process and national reforms. Springer, Dordrecht.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/EUuniv

________________________________________

About the Author

Anne Corbett – LSE European Institute

Anne Corbett – LSE European Institute

Dr Anne Corbett is a Visiting Fellow in the European Institute of the London School of Economics and Political Science. She is the author of Universities and the Europe of Knowledge: Ideas, Institutions and Policy Entrepreneurship in European Union Higher Education, 1955-2005, Basingstoke, Palgrave (2005); and a former journalist.