Last weekend’s election saw GERB continue as the largest party in Bulgaria’s parliament, a success for former Prime Minister Boyko Borisov. Antoaneta Dimitrova argues that while European commentators may see the election result as confirmation of the government’s good management of the country, the low turnout of 53 per cent suggests that Bulgarians have become disenchanted with GERB and the country’s political system. Recent protests over government corruption, and an electoral system that means 25 per cent of voters are not represented in parliament, may mean more troubled times are ahead in Bulgarian politics.

Last weekend’s election saw GERB continue as the largest party in Bulgaria’s parliament, a success for former Prime Minister Boyko Borisov. Antoaneta Dimitrova argues that while European commentators may see the election result as confirmation of the government’s good management of the country, the low turnout of 53 per cent suggests that Bulgarians have become disenchanted with GERB and the country’s political system. Recent protests over government corruption, and an electoral system that means 25 per cent of voters are not represented in parliament, may mean more troubled times are ahead in Bulgarian politics.

As so often happens with news from Bulgaria, the results from the recent Bulgarian elections look different from European and Bulgarian perspectives. The elections can barely be explained through existing political theoretical paradigms, for example of theories of democracy, and the gap between democratic theory and Bulgarian realities has never seemed so large. Leaving aside analysis of the concrete results and the difficulty of forming a government based on an almost perfectly split parliament, at present no single perspective can help us understand what the results tell us about the future of Bulgaria’s political system. This could be also the only good news from these elections.

From a European perspective one could say the elections were won by a right centrist party (GERB) supported by other European Christian Democrats, center right parties and the European People’s Party Group. As recently as 2011, Joseph Daul, the EPP group chairman, congratulated GERB leader and former Prime Minister Boyko Borisov for his government’s good financial management, progress achieved in improving key infrastructure and limiting unemployment.

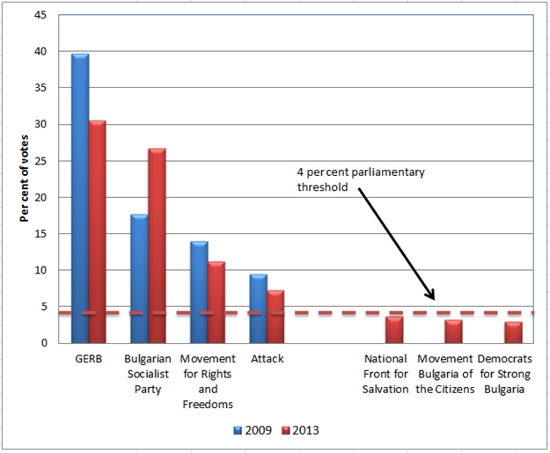

Figure One – Bulgaria election results 2009, 2012

With its small, but clear lead of 30 per cent of the votes or 98 seats, as shown in Figure One, GERB is now a second time winner of parliamentary elections, even third time if we count local elections. This could be interpreted as a sign of stability and satisfaction with Bulgaria’s current economic policy of balanced budgets. Bulgaria has been described by some as ‘a model of fiscal probity’, yet the current results are not really a reward by the electorate given continued policies of austerity and the lowest salaries and pensions in the EU.

The moment one looks closer, the picture of a country being led by a good member of Europe’s right centrist parties falls apart in blurry smudges like an impressionist painting. A closer look reveals continued economic hardship, the failure to raise living standards, increasing unemployment and above all, evidence of state capture by GERB politicians and associated businessmen, supported by a police and secret service apparatus that were meant to be strengthened as part of the fight against organized crime. Among last year’s revelations, which helped to seriously damage GERB’s image, systematic illegal wiretapping of the conversations of ministers, politicians and public figures by the secret service seemingly ordered by GERB’s minister of the interior was discovered.

In addition, there were favours for monopoly businesses with offshore registration led by figures linked to GERB structures, to ministries and parliament and to Borisov personally. There have also been systematic allegations of violations of proper procedure and rule of law in development and public procurement contracts, and the arbitrary appointments of personal favourites for key posts. These have been hastily withdrawn on occasion, as was the case for Bulgaria’s failed first nominee to the European Commission, former Foreign Minister Roumyana Zheleva in 2010. On the basis of their almost complete mandate, GERB have turned out to be much less good news for Bulgaria’s struggle with state capture and corruption than they have claimed. From this perspective, GERB’s second win seems more like a continued grip on power by somewhat authoritarian leaning right wingers than just rewards for good policy results.

Bulgaria’s elections and their outcome, and above all the lowest, at 53 per cent, turnout in the history of post communist democratic elections, represent a challenge for accepted tenets of democratization theory. Namely, that a democratic transition is complete when no major actor challenges the rules of the democratic game. Here, the challenge does not come from established parties that suddenly change the constitution, as has happened in Hungary, but from citizens themselves who no longer see the constitution as democratic enough to allow them sufficient participation. This was evident not only from the election’s turnout but from the protests of January to March this year – the largest since 1997.

Ostensibly the protests’ original cause was high electricity prices, but later they voiced chaotic and unarticulated, but persistent complaints against the existing electoral system and political parties, state capture, uncontrolled monopolies and the state assisted grip of certain groups of shady businesses on policy sectors and even whole towns like Varna. The number of seats in parliament, the parliamentary threshold of 4 per cent, which prevents many new formations from entering parliament, the proportional system of representation that does not allow preferential votes, the lack of real citizen consultation in policy making have all now been questioned by a sufficiently broad group of Bulgarians. One may now conclude that there are major actors who question Bulgaria’s constitution and institutions, but that these are not among the established political parties.

GERB’s tactical resignation in February this year, and call for early elections may have left them with enough support to win, but in combination with last summer’s environmental protests and the election results, voters have made it clear that they do not like the rules of the game as played in Bulgaria at the moment. Not only has this election been marred by low turnout, but the four parties that have made it into parliament represent only 75 per cent of the votes cast. There has been a considerable vote for small parties that did not make it above the 4 per cent barrier. Both of these facts suggest that those who think something is wrong with Bulgaria’s current political system comprise a sufficiently large part of the citizens of the country that we should all be worried not about stability, but about change.

Please read our comments policy before posting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/10HOR4M

________________________________________

About the author

Antoaneta Dimitrova – Leiden University

Antoaneta Dimitrova – Leiden University

Dr. Antoaneta L. Dimitrova is Associate Professor at the Institute of Public Administration, Leiden University.

2 Comments