David Cameron has promised to hold a referendum on Britain’s EU membership in 2017. Costas Milas argues that talk of an exit from the EU has been a hugely unnecessary distraction that has led to economic uncertainty and higher borrowing costs. He shows this by plotting the 10-year UK yield together with the Google trends search queries index for “Brexit”. Policymakers in favour of continuing EU membership need to be vocal about why an exit would be harmful and the Bank of England should monitor Brexit talk in order to counteract its impact.

David Cameron has promised to hold a referendum on Britain’s EU membership in 2017. Costas Milas argues that talk of an exit from the EU has been a hugely unnecessary distraction that has led to economic uncertainty and higher borrowing costs. He shows this by plotting the 10-year UK yield together with the Google trends search queries index for “Brexit”. Policymakers in favour of continuing EU membership need to be vocal about why an exit would be harmful and the Bank of England should monitor Brexit talk in order to counteract its impact.

The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has just noted that the recent rise in sterling borrowing costs is not justified by developments in the domestic economy. In fact, a number of commentators relate the recent rise in the 10-year UK yield to Fed’s talk about reversing its economic stimulus (also known as Quantitative Easing).

In our view, this is partly true as it ignores the possible effects of the so-called Brexit talk on the domestic economy. Prime Minister David Cameron promised in January 2013 to try to renegotiate Britain’s membership of the EU and to hold an in/out referendum on the issue if he wins the next national election in 2015. Since then, Britain’s policymakers have done almost nothing in spelling out the possible economic benefits of an EU exit. Instead, Brexit is a big and unnecessary distraction which adds to economic uncertainty and already impacts negatively on the economy through higher borrowing costs.

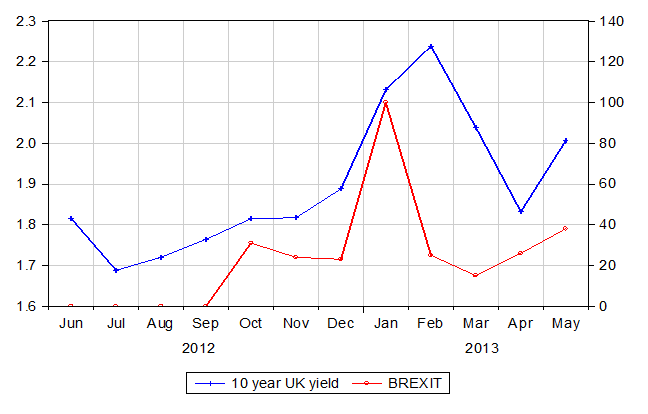

To see this, Figure 1 plots the 10-year UK yield together with a Brexit talk index. The latter refers to the Google trends search queries index for “Brexit” (this is freely available here). The index, which peaked in January 2013 (at the very time of David Cameron’s referendum announcement), is highly correlated with the UK yield (the correlation is equal to 0.67).

Figure 1: UK 10-year yield (Left Hand Side) and Brexit talk (Right Hand Side, based on Google trends), 2012-2013 (monthly data)

Noting that (high) correlation does not necessarily imply causation, we pursue the issue further by running a Granger causality test (named after Clive Granger, the 2003 Nobel Prize Winner in Economics) which suggests that Brexit does indeed cause movements in the 10-year yield (the null hypothesis of lack of causality is rejected at the conventional 5% level of statistical significance). Obviously, the statistical test result needs to be treated with some caution because of the short sample. Nevertheless, the policy implications of our analysis are the following:

- With the UK economy still in a fragile state, Brexit puts upward pressure on UK borrowing costs and undermines the prospects of an early and meaningful recovery. To counteract this, those UK policymakers truly in favour of EU membership need to step up their engagement with the public in spelling out in a clear and concise manner why an EU exit will be harmful.

- The Brexit talk also poses a huge challenge to monetary policymakers. Indeed, Bank of England new governor Mark Carney and the MPC need to keep a close eye on developments in the Brexit front. Although Brexit is beyond the Bank’s control, it should definitely become an input in future monetary policy decisions. To the extent that the Brexit talk puts upward pressure on interest rates, monetary policymakers should be prepared to counteract this by supporting the economy through additional Quantitative Easing, a decision they would have not necessarily taken otherwise.

This article first appeared at the LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/12Su5Az

_________________________________

Costas Milas – University of Liverpool

Costas Milas – University of Liverpool

Costas Milas is Professor of Finance at the Management School, University of Liverpool. He is an expert on Monetary Policy issues such as interest rate setting behaviour and debt policies pursued by the Eurozone peripheral economies (Greece, Italy, Ireland, Spain and Portugal).

Why does this analysis work for “Brexit” but not for “Brixit”, which is what the Economist calls it?

The Economist was the only place I saw “Brixit”. But a quick Google shows 150,000 Brixits and 200,000 “Brexits”. So how we will agree anything about the UK’s relationship to the EU I’ve no idea.

Yes, but why is Brexit talk supposedly hurting the economy, but Brixit talk isn’t?

The mere proposing of a EU membership referendum causes uncertainty. And this has its implications.

Suppose you’re a university graduate. Are you going to apply for a job as a EU public servant if, five years from now, the UK might well no longer be an EU member? No. The UK withdrawing from the EU would leave you stranded in Brussels.

As a university graduate from the UK surely you would seek employment to return the investment your country has put in your education? As a public servant in the EU, based upon several decades of precedent, you would be working for the destruction of the nation of your birth, thereby would perhaps deserve to end up stranded in what was once the capital of Belgium