Southern European countries have been hardest hit economically by the Eurozone crisis. Using Eurobarometer data, Sonia Alonso notes that this economic disparity has also had a significant effect on public attitudes. Citizens in Southern European countries now have substantially less trust in government, trust in political parties, and satisfaction with democracy than those in the North. She argues that allied with shifting political attitudes, this breach is likely to lead to increasingly polarised views, creating a new economic and territorial cleavage between north and south.

Southern European countries have been hardest hit economically by the Eurozone crisis. Using Eurobarometer data, Sonia Alonso notes that this economic disparity has also had a significant effect on public attitudes. Citizens in Southern European countries now have substantially less trust in government, trust in political parties, and satisfaction with democracy than those in the North. She argues that allied with shifting political attitudes, this breach is likely to lead to increasingly polarised views, creating a new economic and territorial cleavage between north and south.

Some weeks ago Lluis Orriols wrote an interesting article about the emerging “ideological divorce” in Europe between the so-called PIIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain) and the rest of the EU countries. While the former are increasingly moving to the left, the rest of Europe is gradually moving to the right.

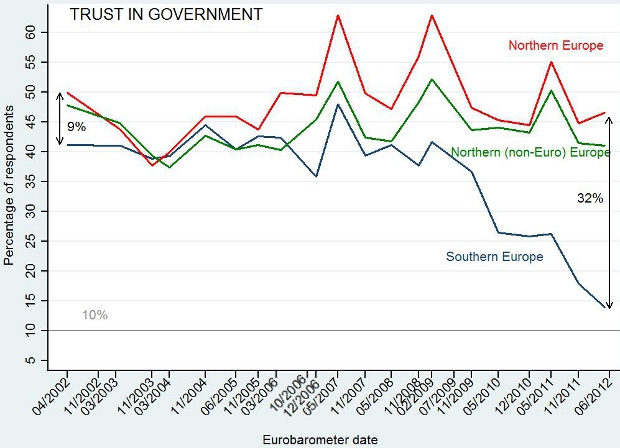

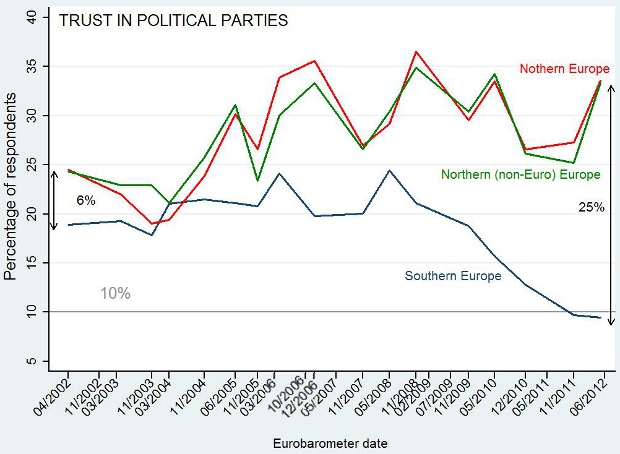

This divorce is not just ideological; it extends to the levels of trust in, and satisfaction with, the representative institutions of European democracies. In order to see this, let us look at Eurobarometer data between 2002 and 2012. I have grouped EU countries into three non-exhaustive categories: Southern Europe (Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain), pro-austerity Northern Europe (Germany and its allies, Finland, Netherlands and Austria) and Northern EU countries outside the euro (Denmark, Sweden and UK). Charts 1 and 2 show the evolution of trust in government and political parties for these groups of countries during the last ten years: five years before the crisis and four years after.

Chart 1: Evolution of trust in government (2002-2012)

Source: Eurobarometer 2002-2012

Source: Eurobarometer 2002-2012

Chart 2: Evolution of trust in political parties (2002-2012)

Source: Eurobarometer 2002-2012

Source: Eurobarometer 2002-2012

The high and low peaks of the charts indicate that levels of trust in government and political parties are highly affected by context. Proximity to elections, political scandals, and economic and international crises are factors that have a direct positive or negative effect on the levels of trust. Despite this “bumpy” trajectory, however, the graph clearly shows the emergence of a gap in European public opinion between the North and the South since the outbreak of the economic crisis. Let us start with the North.

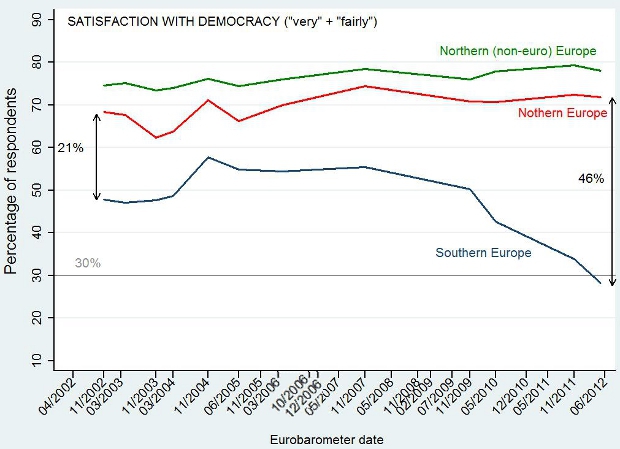

In Northern EU countries, political trust has remained above its 2002 levels since Lehman brothers filed for bankruptcy in September 2008 (with similar values for the countries inside and outside the euro). Both trust in government and in political parties peaked between September 2008 and February 2009, when European governments and governmental parties were united in implementing anti-cyclical reforms, and when European politicians were talking about the need to re-invent capitalism and to increase the levels of regulation of financial markets, while simultaneously blaming the US and its “free-market-above-all attitude” for what had happened. After this peak in trust, levels went down in 2010 and 2011, the years of the Southern European bailouts, but grew again in 2012, particularly trust in political parties, which jumped from 25 per cent in November 2011 to nearly 35 per cent in June 2012, at a time when austerity policies were well entrenched among EU institutions and Northern European chancelleries. Satisfaction with democracy in Northern EU countries has evolved in a similar way. It is less “bumpy” than political trust, for it is less dependent on contextual factors, but the upward tendency is clear even if modest, as shown in Chart 3.

Chart 3: Evolution of satisfaction with democracy (2002-2012)

Source: Eurobarometer 2002-2012

Source: Eurobarometer 2002-2012

In Southern Europe, by contrast, trust in governments and parties has consistently declined since February 2009: a drop of 27 points for governments and 15 points for parties in just four years. In June 2012 only one in ten Southern European respondents trusted its government and its political parties. If we look at the last ten years, the gap in political trust between the North and the South of the EU has grown from 9 per cent to 32 per cent for governments, and from 6 per cent to 25 per cent for political parties. Satisfaction with democracy has also dropped quite dramatically. The gap in the last ten years has grown from 21 per cent (already a quite remarkable gap) to 46 per cent. This is what I call the “democratic breach”.

Until here, I have presented the facts (or, rather, the data). According to these data, European public opinion is increasingly divided along territorial lines. Democracies in the North have recovered and even surpassed the levels of political trust and satisfaction with the political system that they enjoyed ten years ago; democracies in the South suffer levels of political trust and satisfaction in free fall.

How can we interpret these data? This is the part in which I necessarily resort to (informed) speculation, given that I have not done a proper causal analysis of this democratic breach. Northern European citizens are increasingly content with their governments and parties and satisfied with their democracies, in relative terms. It is hard to see how Northern European citizens can be content, given the dramatic situation in the EU, plagued by economic stagnation, increasing levels of inequality, weakened welfare states, internal devaluations, powerless trade unions, feeble economic prospects, and so on. In my opinion, the reason why Northern European publics trust their representatives is, quite simply, that they feel represented, that they feel their interests taken into account.

Why is this so? Because Northern European Eurozone governments are pursuing an economic policy of austerity whose effects are most visible in the South, not in their own countries. Northern European citizens oppose further bailouts of Southern countries because they (wrongly) believe that these bailouts are a way of paying Southern European debts with Northern European taxes. Pro-austerity governments attract their voters with narratives about the need to impose austerity and fiscal discipline on Southern European profligate states and frame their actions as a way of saving their domestic tax-payers’ money while, at the same time, these very same governments cash in the intended (lending at market interest rates) and unintended (paying very little for their own debt) benefits for their state coffers from the Southern European debt crisis.

This is a classic example of overlapping territorial and economic cleavages. Creditors are in the North, debtors in the South, and the interests of creditors and debtors are totally at odds with each other. A process of internal colonialism seems to be emerging inside the EU. This process is compounded by the “ideological divorce” between North and South mentioned at the beginning. Historically, such overlaps between territory, economy and ideology have seldom been conducive to moderation in the settlement of political and economic conflicts. On the contrary, they reinforce each other in polarised directions. We seem to be heading towards a perfect storm.

This article was first published in Spanish by Agenda Pública

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/13vZqrC

_________________________________

Sonia Alonso – Social Science Research Center Berlin (WZB)

Sonia Alonso – Social Science Research Center Berlin (WZB)

Sonia Alonso is a Research Fellow at the Social Science Research Center Berlin (WZB).

But increasing tensions are not contained to the euro periphery alone. S&P has downgraded the growth prospects for the Netherlands and fears the Dutch economy will be weak for years to come. The economic troubles and euroscepticism have resulted in the populist, right-wing PVV of Geert Wilders to rise to the first place in the polls. The current governing coalition parties would lose big time.

In Finland the anti-euro and anti-immigrant True Finns are also doing very well in the polls. If elections were held today, the party would end in second place.

In France President Hollande is forced to deal with scandals within his cabinet, unruly unions, and the French weary of EU interference and austerity (although the French have barely started cutting the government). The latest setback for the President is that he felt he had to sack his Environment Minister Delphine Batho after she publicly criticized a 7% cut to her departmental budget as part of the French government’s plans to cut total public spending by €14bn next year.

Yes, austerity seems to make people blame others for any problems. And it destroys any solidarity feelings that may have been there in the past. Both between and inside countries. This is because austerity is sold with the argument that ‘there is no alternative’ .. so it seems that the choice for austerity is not a choice.

AUSTERITY is not only wrong. There is an alternative. British Senior Citizens Party have been spelling out the alternative for over two years.

Very interesting. Im making my thesis specifically on this same issue. I have been this very weekend in this international conference on the subject: http://uaces.org/events/calendar/event.php?id=814

precisely in Berlin!! 🙂

Part of the problem is the framing of the crisis (through cultural biases), the drift towards informal and intergubernamental decision making processes in the EU and, also, the existence of preexisting cleavages inside the decision making political institutions. All of this is loading this “”cleavage”” (i should say division).