Britain currently uses a closed-list system for the European Parliament elections, allowing voters only to express support for a parties as a whole. An open-list system would allow a voter to choose a candidate from one of the mainstream political parties, whilst still expressing her preferences on the European issue through the selection of a party. Since their exists substantial intra-party diversity. Jack Blumenau, Andy Eggers, Dominik Hangartner and Simon Hix ask whether voters behave differently if they were able to vote for individual candidates, rather than political parties as a whole? Through a new survey experiment, they show that if an open-list system were to be used (as it is in most European countries), then a significant portion of UKIP votes would end up switching to the Conservative party.

Britain currently uses a closed-list system for the European Parliament elections, allowing voters only to express support for a parties as a whole. An open-list system would allow a voter to choose a candidate from one of the mainstream political parties, whilst still expressing her preferences on the European issue through the selection of a party. Since their exists substantial intra-party diversity. Jack Blumenau, Andy Eggers, Dominik Hangartner and Simon Hix ask whether voters behave differently if they were able to vote for individual candidates, rather than political parties as a whole? Through a new survey experiment, they show that if an open-list system were to be used (as it is in most European countries), then a significant portion of UKIP votes would end up switching to the Conservative party.

In the 2013 local elections, the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) had its best national performance to date. UKIP won 26 per cent of the vote in the areas where they competed, thus gaining 139 council seats. It has been widely suggested in the media that UKIP’s growing support stems from Eurosceptic voters who have traditionally voted Conservative, but have become disillusioned with the party’s stance on the EU. Many commentators have predicted that UKIP may go on to win the 2014 European Parliament elections, and early polls have painted a similar picture (for example, see here and here).

(Credit: Euro Realist Newsletter)

However, a new survey experiment that we’ve conducted shows that a change in the electoral system could cause significant differences in party vote shares in the 2014 election. Specifically, we demonstrate that if the electoral system allowed voters to express preferences for individual candidates, and not simply for political parties (as is the case now), UKIP’s vote share would decrease markedly, and the Conservative share would increase. Furthermore, we also show that this effect is driven by Eurosceptic voters opting to vote for Conservative candidates, rather than UKIP ones.

The results of this survey experiment are interesting not only in relation to the forthcoming European elections, but also more broadly for our understanding of the impact of electoral rules on voting behaviour.

Context

In European elections, each EU member state is able to select its own electoral system, so long as the system is a form of proportional representation (PR). There are two main variants used across Europe. The first is ‘closed-list’ PR, where parties order their candidates on a list, and voters choose between competing parties. Parties are awarded seats on the basis of how many votes they receive. If a party is awarded one seat, the first candidate listed for that party wins a seat; if the party is awarded two seats, the first two candidates listed win seats, and so on. An example of this type ballot is given below.

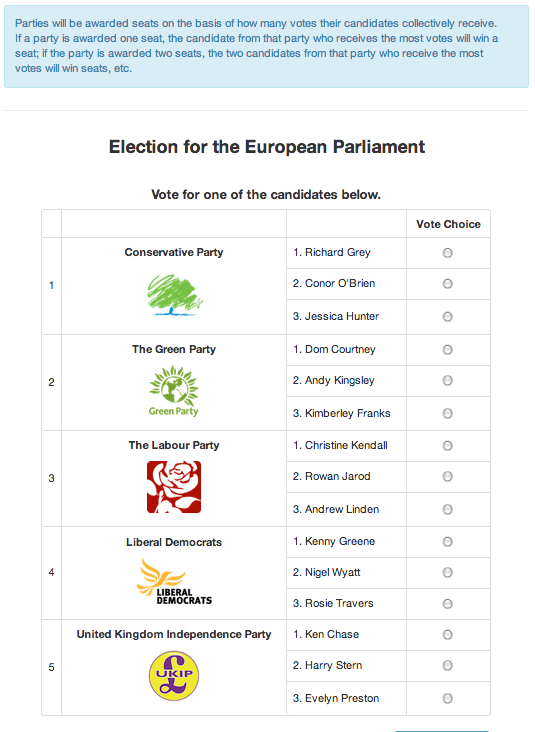

The second is ‘open-list’ PR, where voters choose between parties and candidates. Parties in this system are awarded seats on the basis of how many votes their candidates collectively receive. If a party is awarded one seat, the candidate from that party who receives the most votes will win a seat; if the party is awarded two seats, the two candidates from that party who receive the most votes will win seats, and so on. The open-list system, therefore, allows voters to cast their votes for specific candidates, and not just the party as a whole. This system is used in a majority of EU countries for European Parliament elections. An example of an open-list ballot is shown below.

European elections in Britain are currently conducted under a closed-list system. UKIP has done particularly well in these elections, coming second in the popular vote in 2009 (the Conservative Party came first). There is little doubt that anti-European sentiment has been traditionally high in the UK – a fact that has contributed to UKIP’s success. For example, when we asked respondents to our survey about their views on the EU, 31% identified themselves as Eurosceptic, and only 18% as pro-EU. The main parties in the UK are generally weakly in favour of EU membership, meaning that UKIP has been able to stake out a position on a ‘European’ dimension of political conflict which cuts across the traditional the left-right divide.

However, there are significant divisions over Europe within the main parties. This is particularly noticeable for the Conservatives, where Eurosceptics and Europhobes represent important factions within the party. This intra-party diversity provokes an interesting question: would voters behave differently if they were able to vote for individual candidates, rather than political parties as a whole? An open-list system would allow a voter to choose a candidate from one of the mainstream political parties, whilst still expressing her preferences on the European issue. So, a Eurosceptic voter would be able to cast her vote for a Eurosceptic candidate, not simply a Eurosceptic party.

Design

To investigate whether voters would behave differently under an open-list system, we implemented a randomized survey experiment. We are mainly interested in the share of the vote received by each political party. The ‘treatment’ we administered to participants was the type of ballot they were asked to fill in – an open-list or a closed-list ballot. Additionally, for some respondents we also provided information about the European position of the candidates.

Information about candidates’ European views took the form of endorsements from two hypothetical campaign groups: Britain Out of Europe, which advocates a repatriation of powers to the UK; and Britain In Europe, which advocates full British involvement in a strong European Union. One candidate from the Conservatives, Labour, Lib Dems, and Greens was randomly endorsed by Britain Out of Europe while another candidate was randomly endorsed by Britain in Europe. All UKIP candidates were endorsed by Britain Out of Europe.

Participants were therefore presented with one of four hypothetical ballot papers for the forthcoming European Parliament elections:

- A closed-list ballot, with no additional information

- A closed-list ballot, with information

- An open-list ballot, with no additional information

- An open-list ballot, with information

A representative survey of more than 9,000 respondents cast votes across these ballots. The names on the ballot papers were hypothetical candidates and were randomly ordered for each separate respondent. By randomizing the assignment of participants across ballots, we are able to identify a causal effect between ballot-type and vote choice.

Party Level Effects

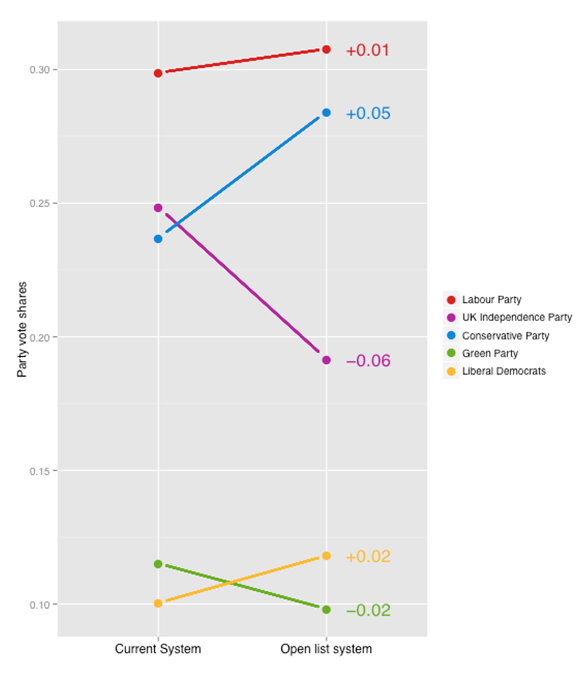

The main findings indicate that the effect of ballot type on party vote share is considerable. Figure 1 shows that under the current voting system – a closed-list system – Labour would win the election with 30% of the vote, UKIP would come second with 25%, the Conservatives third with 23%, Greens fourth with 12%, and the Lib Dems last with 10%.

However, if the election were to be held under an open-list system, and voters were informed about the European views of the candidates, party vote shares would look markedly different. Under this system, Labour would still win the election, but the Conservative party would be in second place with 28% of the vote – an increase of five percentage points when compared to the current system. UKIP’s share would drop by six percentage points to 19%. Although the vote shares of Labour, Lib Dems, and Greens all change slightly between ballot-types, none of these differences are statistically significant.

Consequently, it seems that if the voting system were changed to an open-list system, many voters would switch their support from UKIP to the Conservative party. Allowing for within-party competition decreases the support available for UKIP, and increase the overall vote share for the Conservatives. Indeed, the Conservatives could beat UKIP and be considerably closer to Labour if the voting system changed from closed- to open-list.

Individual level effects

We are also able to establish whether the change in aggregate party support does in fact stem from the behaviour of Eurosceptic voters. Before being presented with the different ballots, participants were asked to place themselves on a ten-point pro/anti-Europe opinion scale. This allows us to observe which type of voter changes their behaviour across the different ballots.

Figure 2 shows that when comparing the vote shares for three types of participants – those who are pro-EU, neutral and Eurosceptic – only the Eurosceptic voters change their voting behaviour significantly when presented with an open-list ballot. Moving from the current system to an open-list system results in 8% more Eurosceptic voters supporting the Conservatives, and 16% fewer Eurosceptic voters supporting UKIP. Thus, these findings show that many Eurosceptic voters would vote Conservative over UKIP if they were given the option of casting their vote for individual Eurosceptic candidates.

Conclusion

Our experiment shows that if the electoral system for the European elections in Britain allowed for within-party competition, support for UKIP would decrease, and the overall vote share for the Conservative party would increase. The magnitude of this effect is large, and would have real consequences for the distribution of British seats in the European Parliament.

Thinking more broadly, there are two reasons to expect voting behaviour to differ under different ballot types. First, open-ballots encourage candidates to compete for votes by increasing their constituency work, delivering infrastructure projects, and building a strong local profile. This is because candidates are aware that through these activities they can build their own ‘personal vote’ on the open-list, which improves their election prospects vis-à-vis their co-partisans. The incentives to do this are much lower in the closed-list system (where no personal vote is possible), and we should therefore expect different voting outcomes to the extent that candidates engage in such activities. This phenomenon has been widely studied in the political science literature.

Second, the experiment implemented here shows that the difference between open- and closed-lists also matters when one party takes an extreme position on an issue that divides other parties. Giving voters the opportunity to vote for their preferred candidate (not just their preferred party) allows them to vote for a mainstream party, whilst still enabling them to exercise their preferences on an issue that is orthogonal to the main dimension of political conflict. Our study therefore shows that preferential voting for candidates can matter not just for valence issues, but also when voters have information about the differential policy positions of candidates within political parties.

This article originally appeared at the LSE’s British Politics and Policy blog.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/139iQTA

_________________________________

Jack Blumenau – LSE Government

Jack Blumenau – LSE Government

Jack Blumenau is a PhD student in the Department of Government at the LSE. He completed an MPhil in European Politics and Society at the University of Oxford in 2012, having graduated from the LSE with a degree in Government in 2010. His research interests include legislative and party politics, particularly in relation to the European Union.

Andy Eggers – LSE Government

Andy Eggers – LSE Government

Andy Eggers is a Lecturer in Political Science in the Government Department at the LSE, having joined the school in 2011. He received his PhD from Harvard University in 2010, after which he spent a year at Yale University as a post-doctoral research fellow in the Leitner Program in International and Comparative Political Economy.

_

Dominik Hangartner –LSE Methodology Institute

Dominik Hangartner –LSE Methodology Institute

Dominik Hangartner is a Lecturer in Quantitative Research Methodology in the Methodology Institute at the London School of Economics. After pre-doctoral fellowships at Harvard University, Washington University in Saint Louis, and the University of California, Berkeley, he received his Ph.D. in Social Science from the University of Bern in 2011.

Simon Hix – LSE Government

Simon Hix – LSE Government

Simon Hix is Professor of European and Comparative Politics and Head of the LSE Department of Government. He is co-editor of the journal European Union Politics. He has held visiting appointments at UC Berkeley, Stanford, UC San Diego, Sciences-Po Paris, and the Hertie School of Governance in Berlin. He regular gives evidence to the committees in the European Parliament and the European affairs committees in the House of Lords and House of Commons. He has written several books on the EU and comparative politics, including most recently “What’s Wrong With the EU and How to Fix It” (Polity, 2008). Simon is also a Fellow of the British Academy.

What was the reason for the UK government/parliament/parties to opt for closed lists? It seems that they didn’t have a very high opinion of voters. Were the parties afraid of allowing voters the choice to influence the mix of MEPs that will end up in the EU parliament?

Make it simple… too much scheming…. we vote for Party and a candidate…..