The Riga supermarket tragedy in November prompted the resignation of the Latvian prime minister and the fall of the country’s government. As Licia Cianetti writes, the resignation was largely rooted in party political and ethnic divisions within Latvia, rather than in the tragedy itself. She argues that the upcoming European Parliament and Latvian Parliament elections in 2014 will test whether Latvian politics will remain ethnically divided, or whether the country can make a transition into a stronger left-right political system.

The Riga supermarket tragedy in November prompted the resignation of the Latvian prime minister and the fall of the country’s government. As Licia Cianetti writes, the resignation was largely rooted in party political and ethnic divisions within Latvia, rather than in the tragedy itself. She argues that the upcoming European Parliament and Latvian Parliament elections in 2014 will test whether Latvian politics will remain ethnically divided, or whether the country can make a transition into a stronger left-right political system.

On Thursday 21 November 2013, the roof of a Maxima supermarket in the west Riga neighbourhood of Zolitūde collapsed, killing 54 people and injuring dozens more. The tragedy shook the entire country and, after Latvian Prime Minister Valdis Dombrovskis took political responsibility for it and resigned on 27 November, it created a political aftershock with repercussions that are still difficult to predict.

Dombrovskis’s resignation came one year ahead of the next parliamentary elections, scheduled for October 2014, and only a few months before the European Parliament elections in May 2014. Dombrovskis’ sudden decision to step down exposed the central tensions within Latvia’s complex political landscape. Two crucial (and interlinked) issues that have come to the forefront in the tragedy’s aftermath are the role of the Russophone party Harmony Centre in Latvian politics and the social price of Latvia’s ‘success story’ under Dombrovskis.

Dombrovskis had served as Latvia’s prime minister since 2009 and was confirmed to his post twice after early elections in 2010 and 2011. This makes him the longest-serving prime minister of post-Soviet Latvia. Following his resignation, Latvian President Andris Bērziņš will have to nominate a new prime minister who can secure a confidence vote within the current Saeima (the Latvian Parliament). This is by no means an easy task.

Political landscape

Dombrovskis’ 2011 government was based on a coalition of Unity (the right-wing party to which the resigning prime minister belongs), the nationalist National Alliance and the Reform Party. In the two years of this coalition government, relations among the coalition partners were far from smooth. According to widespread rumours, it was in fact President Bērziņš who pressured Dombrovskis to resign, following months of squabbles within the coalition.

Now, the most probable outcome of the inter-party consultations set off by the resignation seems to be a government based on the current coalition, with the added support of the Union of Greens and Farmers (ZZS). Several names have been put forward for the prime minister of such a coalition, including candidates from Unity (most notably the current Defence Minister Artis Pabriks) and from ZZS, as well as more ‘technical’ figures like the current European Commissioner for Development, Andris Piebalgs.

But this solution does not come without problems. The leading figure within ZZS, Aivars Lembergs, is one of the so-called Latvian ‘oligarchs’ who were ousted from power in 2011 after former President Valdis Zatlers initiated a popular referendum for the dissolution of a parliament that had been marred by corruption scandals. After 94 per cent of those who took part in the referendum voted for the dissolution of the parliament, Zatlers went on to found the Reform Party, which received an outstanding 20.8 per cent of the vote in the last general election on a largely anti-corruption and anti-oligarchs platform.

Not all members of the Reform Party will therefore be ready to go along with a coalition that includes ZZS, which would in all probability completely discredit their anti-corruption credentials. Reformist MP Daina Kazaka accused the president (himself a former member of ZZS) of cynically exploiting the tragedy to force Dombrovskis into resignation and facilitate ZZS’s “readmission” to government. Moreover, in the days following Dombrovskis’ resignation, a number of prominent members of the Reform Party have left the party, including the Minister for Environmental Protection and Regional Development, Edmunds Sprūdžs. They pointed to the party’s lack of internal democracy and its betrayal of their mandate to the electorate as their main reasons for leaving. The Reform Party’s embarrassingly low approval ratings after two years as part of the shaky governing coalition is probably also part of the explanation.

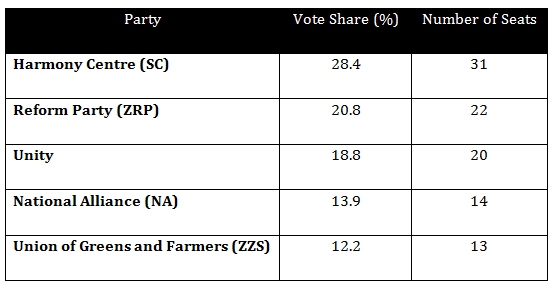

A crucial factor in the discussions on the formation of the next government is the absence of any reference to the largest party in parliament, Harmony Centre, as possible coalition member (let alone coalition leader). Harmony Centre is the party of reference for Latvia’s large Russian-speaking minority, and currently the only Russian-speakers’ party to be represented in parliament. The party came in first place in the last parliamentary elections with a remarkable 28.4 per cent (as shown in the Table below).

Table: Vote share and number of seats in the 2011 Latvian elections

Source: European Election Database

Harmony Centre has also governed the capital Riga since 2009 with the popular Russophone Mayor Nils Ušakovs (re-elected in June 2013 with 58 per cent of the vote). These percentages exceed the share of Russian-speakers in Latvia’s and Riga’s electorate and have been seen as an indication that an increasing portion of the Latvian-speaking electorate might be turning to the party.

Analysts have pointed to the fact that Harmony Centre is the only leftist party in Latvia’s right-wing-dominated political landscape as the likely explanation for this shift. However, Harmony Centre is still widely regarded as the ‘party of the Russians’, which has so far contributed to keeping it consistently out of government. The ethnic undertones of the current debate over Latvia’s post-Dombrovskis political future were made clear by Saeima Speaker Solvita Āboltiņa (Unity). She called for the (ethnic) Latvian parties to stay united at this difficult juncture, presumably to stave off the risk of the ‘Russians’ getting into power.

Although Harmony Centre’s participation in the creation of the new government has largely been blocked by all of the other parties, its main figure, Nils Ušakovs, is at the very centre of the current debate. Following Dombrovskis’ resignation, the pressure has been mounting for the mayor of Riga to resign as well. His political adversaries organised a demonstration in front of Riga City Council on Tuesday 3 December to call for the mayor to step down. However, far more people turned up for the simultaneous pro-Ušakovs demonstration.

While both demonstrations might reflect the opposing parties’ organisational capacities more than genuine popular mobilisation, the fact that the opponents of Ušakovs could not bring more than fifty people to the square is still a good indicator of the level of widespread support the ‘Russian mayor’ enjoys in the capital city. Ušakovs rebuffed pressure to resign from the very beginning, presenting himself as the only leader who is responding to the tragedy with actions rather than fleeing from responsibility (like Dombrovskis) or concentrating on playing party politics.

In a recent article printed in both the Latvian and Russian-language media, Ušakovs referred to the other parties’ discussions on government formation only days after the tragedy as “sickening bacchanalia”. Since the budget has already been approved and no changes can be made until the summer, Harmony Centre has asked the president to form a non-political, caretaker government, with the support of all the parties in parliament, which would administer the country until the next elections. At this stage, no other party has expressed support for such a solution, although this has not been dismissed outright by the president.

With Harmony Centre standing little chance of being included in any governing coalition, Ušakovs is clearly positioning himself and his party with a view to next year’s elections. It is reasonable to expect that Dombrovskis’ economic and social legacy is going to be at the centre of the political debate in both the elections to the European Parliament in May 2014 and the elections to the Saeima in October 2014. The Maxima supermarket tragedy will likely play a part in this debate and different interpretations of how it is linked to Dombrovskis’s economic policies are already being voiced.

Austerity and the Zolitūde tragedy

Dombrovskis’ years in office were focused on managing the economic crisis that had severely hit Latvia’s banking system in 2008 and had left the country with an unemployment rate of 20 per cent. Dombrovskis’ cabinets followed the austerity measures steadfastly, and the resigning prime minister has been widely acclaimed for having saved Latvia from economic disaster. Latvia’s GDP growth rate is now solidly above the EU average, unemployment has been reduced, and the country will be introducing the euro in January 2014. Dombrovskis celebrated his success as a model for other countries in a book he published in 2011 with Swedish economist Anders Åslund, entitled How Latvia came through the financial crisis.

Critics, however, argue that this ‘success story’ came at an excessive social price, and that the entrance to the Eurozone has been paid for with high levels of poverty and inequality, and worrying emigration figures (Eurostat data confirm these negative trends). The Maxima supermarket tragedy brought these issues to the fore and along with it a dramatic reengagement of the debate on the costs of austerity.

The extremely poor labour conditions of Maxima’s employees made the front pages of both Latvian-language and Russian-language newspapers, raising questions about the role of workers’ rights in Latvia’s economic growth model. Similarly, news about the poor pay received by firefighters and the fact that the state does not provide them with adequate health insurance caused widespread public opprobrium, especially since three firefighters died during the rescue mission.

Harmony Centre, the only major party in Latvian politics that positions itself on the political left, did not miss the opportunity to link the tragedy to the government’s austerity policies. In public statements following the tragedy, Ušakovs and others in his party presented the roof collapse as the direct consequence of the government’s decision in 2009 to disband the State Building Inspection Office, privatise the system of building certifications and pass all supervisory responsibility to the local administration without allocating appropriate resources. Harmony Centre accuses the government of having ceded too much to lobbying by developers and international investors and, in so doing, of having put its policy of ‘consolidation’ – that is, privatisation and reduction of state expenditures – before its own citizens’ lives. It remains to be seen whether these arguments will gain traction with large segments of the public.

With a year of elections ahead, the Zolitūde tragedy is likely to become not only a central focus of political campaigning (especially concerning the direct and political responsibility for the deaths), but also a potential catalyst for discussion of Dombrovskis’ legacy and the social price of Latvia’s economic ‘success story’. All the parties will have to position themselves within this debate. In this scenario, Harmony Centre will have to negotiate its position between being the biggest party which represents Latvia’s Russophone minority, and its role as a non-ethnic leftist party. If it does this successfully (which is extremely difficult, but not completely out of the picture), Latvia’s party system will be structured less rigidly along ethno-linguistic lines and its left-right dimension will increase in importance.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1gjzU5c

_________________________________

Licia Cianetti – University College London

Licia Cianetti – University College London

Licia Cianetti is a PhD student in the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at University College London. Her primary research interests are in minorities, democratic representation and power. Her PhD research concerns the political representation of Russian-speaking minorities in Latvia and Estonia and their access to the policy making process.

Very similiar to what we are seeing in the south of Europe, an artificial recovery based on social cuts and extreme austerity. It’s normal that people turn towards the ‘old regimes’ in which the state took care of the majority’s welfare. In eastern Europe that smells mostly of socialism and in the south of fascist or, at least, ‘non-democratically elected’ regimes.

For more information on president Andris Bērziņš’ efforts to form a new government see this post: http://presidential-power.com/?p=468

It wasn’t mentioned in the article that Harmony Centre has strong political ties with Russia (Putin’s Edinstvo and Russia Embassy in Riga), is pushing for different interpretation of well-known history, and challenging Latvian culture and values. While the care for the large Russian minority is admirable, at the same time it’s obvious this party (just like pro-Latvian National Alliance) is consciously encouraging national segregation as a tool of building its political capital. Even more so, they play both sides, by giving differing statements to the Russian and Latvian press.

Also, while Nils Ushakovs enjoys large popularity as Mayor of Riga, it is clear that the biggest supporters are Russians who are not shy to admit their national preference. For the rest, the extremely sophisticated PR is working well — the publicity for each step the Mayor takes is carefully planned from the get go, in fact quite probably it’s the basis of most of the actions undertaken.

If you research influence of Russians in Latvian politics, you don’t have to look at HC exclusively — there have been quite some Russians in high posts coming from different, not necessarily ethnically oriented parties — but I guess you know that.