Have humans always waged war? Is warring an ancient evolutionary adaptation or a relatively recent behaviour? In this book, editor Douglas P. Fry brings together leading experts in evolutionary biology, archaeology, anthropology, and primatology to find answers to fundamental questions about peace, conflict, and human nature in an evolutionary context. Anthony Oruna-Goriaïnoff finds it a comforting thought that our ancestors, at their most primitive, and for a long time after, were happier living in peace and avoided war even though the preconditions for war have been part of humanity from the start.

Have humans always waged war? Is warring an ancient evolutionary adaptation or a relatively recent behaviour? In this book, editor Douglas P. Fry brings together leading experts in evolutionary biology, archaeology, anthropology, and primatology to find answers to fundamental questions about peace, conflict, and human nature in an evolutionary context. Anthony Oruna-Goriaïnoff finds it a comforting thought that our ancestors, at their most primitive, and for a long time after, were happier living in peace and avoided war even though the preconditions for war have been part of humanity from the start.

War, Peace, and Human Nature: The Convergence of Evolutionary and Cultural Views. Douglas P. Fry. Oxford University Press. April 2013.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that war is as old as human civilization. Certainly that seems to be the view of many scholars and politicians. That war is as old as we are; that, given the latest examples of human behaviour when at war, it will be with us until we are no longer around. Although that second posit is not one which can be entertained here, the first one certainly can be challenged, and forms the focus of War, Peace, and Human Nature, edited by Douglas P. Fry. This hefty and fascinating book presents readers with 27 chapters devoted to challenging the idea that humans have always been attuned to war.

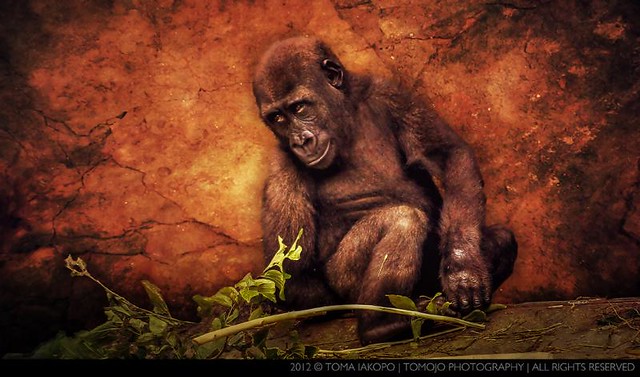

And how best to understand human behaviour than by studying the behaviour of species most closely related to us? In the chapter ‘Chimpanzees, Warfare and the Invention of Peace’, Michael Wilson asks if warfare is an invention or an adaptation, and adds to the dialectic started by Hobbes, who spoke of “Warre” as being the natural state of humans with strong institutions (the “Leviathan”) and Rousseau, who argued that “people were basically peaceful and cooperative”, unless institutions got in the way. Wilson sides with Rousseau, using archaeology, ethnography, as well as animal behaviour, to argue his point. Naturally, our cousins are aggressive and capable of killing their own. But Fry argues that their use of aggressive behaviour is selective, “escalating to damaging fights only when the stakes are high”. The reasons for intraspecific aggression, which seems to be a widespread trait of chimpanzees and not the result of circumstances peculiar to a few study sites, range from territorial defence to availability of resources. Nonetheless, the territorial aspect of the species may play a larger part than has been thought before, since there is now a growing body of evidence supporting the idea that “male chimpanzees seek to defend and expand a feeding territory for themselves, their mates and offspring.”

So how is their behaviour co-relatable to that of humans? According to the author, long-term data makes it clear that chimpanzees “regularly live under circumstances that Hobbes would describe as Warre.” He further argues that warlike behaviour in chimpanzees appears to be “adaptive in that participation leads to inclusive fitness benefits.” Their behaviour has been cited as evidence against arguments (Mead, 1940) that warfare is an invention. Nevertheless, according to Wilson, “the special features thought to be needed for humans to become warlike”, such as weapons, agriculture, ideology, states etc are “not present in chimpanzees” and yet they suffer “rates of intergroup killing comparable to human societies with endemic warfare.”

The difference the author stresses is that, unlike chimpanzees, human societies see a benefit in cooperation, trade etc. So if we seem to be predisposed to conflict, shouldn’t human history be laden with examples and clear evidence of war?

According to R. Brian Ferguson, author of the chapter ‘The Prehistory of War and Peace in Europe and the Middle East’, instances of war in early human history are rare. Ferguson argues that whenever there is war, it leaves a trace, so to think that war somehow could have occurred and not left a trace, though not impossible, would certainly be rare. Ferguson writes that during the Mesolithic period (about 10,000 to 5000 BCE), evidence of war in Europe is inconsistent, and that in the comparable Epipaleolithic period in the Near East, war is just absent, pointing out the fact that it seems to have been absent in that area for at least half a millennium! So the data appears to support the idea that humans have not been at war from the start. In fact, until a certain point in time, data suggest much the opposite.

It is soothing to think that our ancestors, at their most primitive, and for a long time after, were happier living in peace and avoided war (though that is not to say they avoided aggression or violence) even though, as the author points out, the preconditions for war have been part of humanity from the start. That is to say, even though these conditions were there for extended periods of time, there is no evidence of war up until a certain point in time in the case of the southern Levant. And when the signs do appear, they do so very quickly. Towns become fortified in less than 100 years, and signs of war go from 0 to 100% in about the same time period. The author puts this down to the creation of a “tribal zone” in the area, which was a direct cause of the rise of imperial Egypt as the area’s hegemon.

This leads Ferguson to ponder the reasons why people who are at peace most of the time would decide to go to war, especially since, as he argues, it would be extremely difficult to get a people who have no history of collective attacks to start doing just that.

So, what makes humans so predisposed to kill one another in war? In chapter 25, ‘The Challenge of Getting Men to Kill: A view from military science’, Richard J. Hughbank and Dave Grossman waste no time in pointing out the obvious: we are not suited to kill each other. They base their argument on the need to train the midbrain, “or mammalian brain” to trust in military training, “equipment and fellow warrior” in “the chaos known as combat.” Both authors point out that in ancient warfare, and indeed all the way to the present day, when in battle, most of the killing took place when one army managed to make the other one flee. It is much easier to deny the humanity of a fleeing victim with his back turned since you don’t have to look that person in the eyes. Opposition soldiers turn into prey when they run away, so our brains make the transition from ‘killing’ to ‘hunting’, thus enabling humans to kill their own, argue the authors.

Hughbank and Grossman discuss that the best way to get men to kill is to divide the psychological responsibility of killing by distancing the soldier from it as much as possible. This ‘distance’ enables men to get away from the emotional resistance to killing and it has been achieved by getting archers to be driven from a chariot, by putting men together inside a battleship, or two or more crewmen inside a bomber, or by the use of the crew-served machine gun, which they refer to as “the key killer on the close-range battlefield.” So killing other humans is something which must be taught, since there is a natural animadversion to killing our own, and therein lies much of current military thinking.

This book is as fascinating as it is long. The subject matter, as distasteful as it is, is certainly presented in a well thought-out and straightforward manner. If war and peace studies are your target then this book will serve you well. And if they are not, you may be surprised at what you can learn.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1fMkHH1

_________________________________

Anthony Oruna-Goriaïnoff

Anthony Oruna-Goriaïnoff

Anthony Oruna-Goriaïnoff is an LSE alumnus, having studied for an MSc in International Relations. He worked in television and media for several years, and also has a Masters in Journalism. He is currently working at a PR firm as Accounts Executive, and as a freelance journalist. You can follow him on twitter: @GUADALBERRY

1 Comments