While Southern European states have experienced intense economic problems since the start of the financial crisis, the German economy has generally been viewed as comparatively healthy. Mark Esposito argues that beyond positive figures such as the high rate of employment within the country, Germany is not the robust model of economic health which it has been portrayed as. He notes in particular that employment figures are inflated by a greater number of part-time jobs, and that the percentage of German citizens at risk of falling into poverty has continued to rise since the turn of the century.

While Southern European states have experienced intense economic problems since the start of the financial crisis, the German economy has generally been viewed as comparatively healthy. Mark Esposito argues that beyond positive figures such as the high rate of employment within the country, Germany is not the robust model of economic health which it has been portrayed as. He notes in particular that employment figures are inflated by a greater number of part-time jobs, and that the percentage of German citizens at risk of falling into poverty has continued to rise since the turn of the century.

The number of people at risk of poverty grows in Germany, although the number of employed has never before been so high, according to results published by the Federal Statistical Office (Destatis), in December 2013. The study, which takes a snapshot of German society from numerous surveys, shows that in 2012 the country had 41.5 million people employed, the highest in its history. However, the total working volume was at 1991 levels.

As explained in the report, produced in collaboration with the Federal Center for Political Education and the Center for Social Research in Berlin, this is because in the last twenty years the average hours worked per person have dropped continuously. This is due to the fact that since 1991, while a higher percentage of the population works, there has been a significant increase in volunteering and/or part time work as well.

Thus, the number of people without full-time contracts or temporary jobs grew to almost a quarter of the German population (22 per cent), with the worst affected groups including women (33 per cent), those aged 15 to 24 years (33 per cent) and those with no qualifications (37 per cent). This seems to suggest a route to a number of probable imbalances, precursors to problems countries such as Italy and France are experiencing today, causing higher insecurity in society and social pressure on the welfare system.

At the same time, the percentage of the German population at risk of falling into poverty has increased in recent years. Using those receiving less than 980 euros per month as a cut-off point, the report indicates that the percentage of individuals at risk of falling into poverty grew from 15.2 per cent in 2007 to 16.1 per cent in 2011.

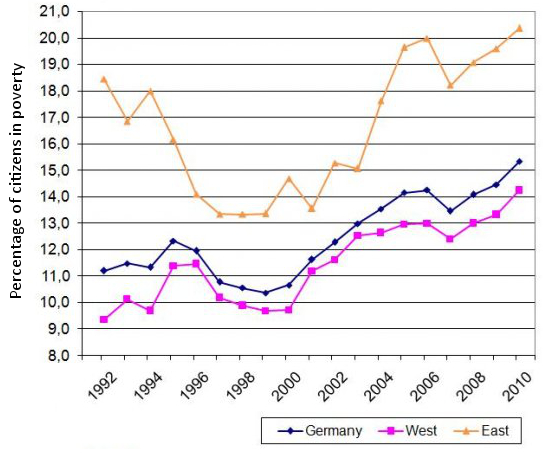

This increase was particularly acute among those aged between 55 and 64, in which the percentage went from 17.7 per cent in 2007 to 20.5 per cent in 2011. It was much less significant among individuals aged between 18 and 24: it grew from 20.2 per cent in 2007 to 20.7 per cent in 2011. These are signs of a “trans-generational deficit” and divide that may cause new financial troubles for the economy with inevitable discontent. As Chart 1 shows, the figures match the general trend of increasing rates of poverty in Germany, particularly in eastern parts of the country.

Chart 1: Poverty rate in Germany by region (east/west, using 60% threshold)

Source: SOEP

According to the study, the percentage of the population suffering “prolonged poverty” increased significantly: 40 per cent of people in 2011 were considered at risk of poverty and had suffered deficiencies in income during the previous five years. In addition, more and more people belonging to the group of those with “less income” judge their health status as “bad” or “worse” than in previous years. If perception is equally important as reality, this could lead to a fall in consumers’ confidence and apathy towards investments or sophisticated consumption (consumption of high-end products). Poverty, according to the report, also influences the life expectancy of the population: life expectancy is eleven years lower for men born in low-income areas than it is for those born in high income areas, whereas for women the difference is eight years.

Thinking ahead

The current German economy, its current excessive account surplus and the deflationary wave this is causing across Europe cannot be scapegoated so easily. It would not be healthy to do so because the European Union is so mendaciously entangled that a German imbalance would generate greater inefficiencies elsewhere. The last thing we would want to do is to distance those investors who have always believed in the strength of the German economy. Let us not repeat the mistakes experienced in Greece and Cyprus, who became passive and unfortunate spectators of a disruptive “finger pointing strategy” that led nowhere.

What we need is a strong integrated union, a political one, which could reinforce policy decisions and learn from respective failures, without “blame” games of this sort. The current situation in Germany invites everyone to play an important role and to discontinue this dependency on one country. Germany is not the centre of Europe and the sooner we understand it, the sooner Germany will be able to fix its own woes and alleviate itself from this burdensome role. Only by shifting our perception from a patchwork of member states, to an integrated system “United in diversity”, will Europe be given life of its own.

A version of this article originally appeared at the Huffington Post

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1iRij5x

_________________________________

Mark Esposito – Grenoble Graduate School of Business

Mark Esposito – Grenoble Graduate School of Business

Mark Esposito is an Associate Professor of Business & Economics at Grenoble Graduate School of Business in France, an Instructor at Harvard Extension School, and a Senior Associate at the University of Cambridge-CPSL in the UK. He serves as Institutes Council Co-Leader, at the Microeconomics of Competitiveness program (MOC) at the Institute of Strategy and Competitiveness, at Harvard Business School. He is also the Founding Director of the Lab-Center for Competitiveness. His full profile can be found at www.mark-esposito.com and he tweets as @Exp_Mark

1 Comments