The Eurozone crisis has raised doubts about the rationale which underpinned the creation of the single currency. Tal Sadeh writes that despite early difficulties in accurately quantifying the trade benefits brought about by the euro, recent research shows that it has more than doubled trade among its member states. Moreover, while the Eurozone crisis has created more substantial problems in Southern Europe, the trade benefits derived from the single currency have been disproportionately larger in Eurozone periphery states.

The Eurozone crisis has raised doubts about the rationale which underpinned the creation of the single currency. Tal Sadeh writes that despite early difficulties in accurately quantifying the trade benefits brought about by the euro, recent research shows that it has more than doubled trade among its member states. Moreover, while the Eurozone crisis has created more substantial problems in Southern Europe, the trade benefits derived from the single currency have been disproportionately larger in Eurozone periphery states.

With the sovereign debt of Eurozone member states having spiralled in recent years, and an increasing number of them having required bailouts, critics have pointed to the costs of the euro and raised doubts about the usefulness of a common currency in Europe. Many agree that the reasons for establishing Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) have always been mainly political. However, the economic cost-benefit analysis remains important because it helps shape the political debate by either putting a price tag on the project or showing that it pays for itself.

The benefits of a single currency are expected mainly from expanded trade, following the elimination of exchange rate fluctuations and currency conversion costs and the elimination of pricing mark-ups. Currency unions also reduce the fixed costs associated with international trade and allow smaller firms to participate, thus increasing variety-driven trade.

However, convincing evidence to support these solid theoretical arguments has long been scarce. It was only from the beginning of the 2000s that economists, armed with huge datasets and enhanced computing power, were able to show that a currency union, and by implication the euro, triples trade. This initial finding was met with great scepticism by many, who pointed to problems with the methods used.

First, the large estimates were based on data of many small very poor countries. Since rich countries tend to have diversified economies with long-established trade-supporting institutions and legislation, they are more inclined to trade than other countries. So when European countries are compared with low-trading countries, the euro’s effect on trade is conflated with their idiosyncratic tendency for greater trade. It is therefore important to compare the Eurozone Member States with countries that are as similar to them as possible, such as other OECD Member States, which did not adopt the euro.

Second, the euro’s effect on trade must account for the increase in trade that would have occurred without the euro because of the continued integration in the Single Market. Third, the large estimates were also based on data extending back to the 1950s. Back then, trade levels were lower than today, relative to overall economic activity, less based on variety, more hindered by transportation, communication and logistics costs, and production processes tended to be less globalised. When trade patterns in today’s Europe are compared with trade patterns of the 1950s, the euro’s effect on trade is conflated with globalisation.

Fourth, there were great inaccuracies and distortions in studies of the euro’s effect on trade because they did not properly account for changes in the purchasing power of importing economies and changes in the competitiveness of the exporting countries. As methods improved, successive studies brought down the estimate to no more than a 15 per cent increase, and perhaps even no increase.

However, studies arriving at such low estimates underestimated the euro’s effect on trade because of three other issues. First, few studies accounted for all of the above issues simultaneously, preferring instead to treat them one problem at a time. Second, they did not properly account for trade between members and non-members of the Eurozone. In doing so, they compared trade among Eurozone Member States not only to trade among non-members, but also to trade between members and non-members, which is also stimulated by the euro. In other words, the underestimation resulted from comparing one effect of the euro with another of its effects, rather than with the null case of no effect.

Third, economists so far have ignored the dynamic nature of the relationship between trade levels and the existence of the euro, typically looking for an average estimate across time and Member States. However, consumers and firms may take time to adapt and exploit the possibilities that a new currency can offer, and this adaptation is not necessarily a smooth process. For many, the adaptation only really began ahead of the issuance of the euro notes and coins in 2002.

Even if progress in adaptation would have been steady over time, the euro’s trade effect is sensitive to euro-induced recessions and booms. If Germany was in recession during the euro’s early years because of the common monetary policy, that must have weighed down on the euro’s overall effect on trade. As a result, many studies were simply pre-mature. The euro’s effect on trade cannot be seriously inferred from the experience of just a few years after its launch. New data from more recent years bear the euro’s effect more clearly.

Finally, although less relevant to problems of underestimation, social-political institutions as well as national heritage can cause variations in the euro’s effect in different Member States. If the euro mostly stimulates variety-driven trade, as some have suggested, then it should affect the trade of the different Member States according to the share that small firms make up their production. The Mediterranean economies are especially characterised by small businesses and thus can be expected to gain much from the introduction of the euro. Identifying the trade effects of the euro in the Member States that received bailouts is also interesting, in light of the great efforts to keep them in the Eurozone.

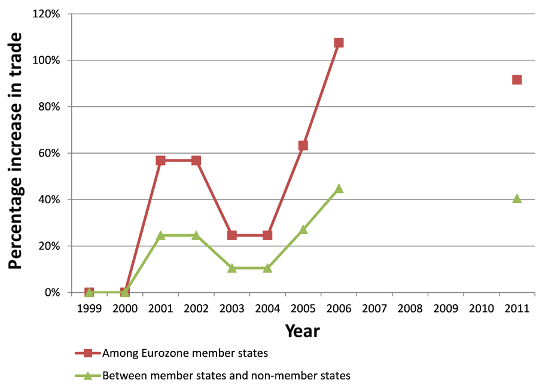

With all the above in mind, newly published research provides strong evidence that the euro indeed has more than doubled trade among its Member States. Chart 1 shows that the euro’s trade effect did not begin to kick in until 2001, but by 2006 it added up to more than 100 per cent among members of the Eurozone and more than 40 per cent between members of the Eurozone and non-members (whether members of the EU or not).

Chart 1: The development of the euro’s effect on trade

Note: See the author’s longer article for further calculations

This means that, all else being equal, in 2006 the trade volume between say, Britain and Germany, would have been roughly 40 per cent smaller had the euro not existed. Unfortunately, for technical reasons such a year-by-year analysis is unfeasible after 2006, but the 2011 values represent an average effect for the entire 1999-2011 period, and suggest that the upward trend of the mid-2000s continued at least until the euro crisis hit in 2010, and that whatever deterioration in the euro’s trade effect may have occurred in 2010-2011, it did not offset the gains made during the 2000s.

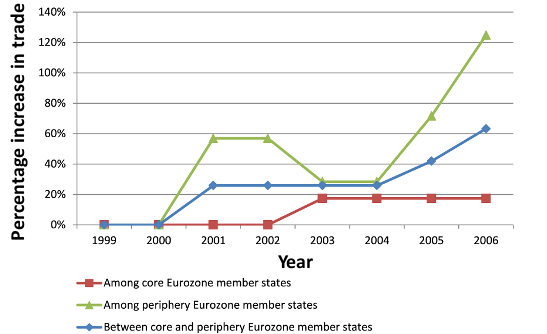

Chart 2 shows that during 1999-2006 the euro increased trade among the periphery countries of the Eurozone (Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Spain) more than among its core member states (Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany and the Netherlands).

Chart 2: The development of the euro’s effect on trade by type of Member State

Note: See the author’s longer article for further calculations

This delayed and fitful progression of the euro’s effect helps explain why it was difficult to detect until now, even with the sounder methods. Overall the evidence suggests that micro-economically the euro works in spite of its macro-economic difficulties, and that in the long run the euro is especially helpful to periphery countries. To the extent that the euro remains a politically desirable project, this evidence strengthens the case for saving it.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1eeVqSp

_________________________________

Tal Sadeh – Tel Aviv University

Tal Sadeh – Tel Aviv University

Tal Sadeh is Senior Lecturer at the Department of Political Science and Head of the Harold Hartog School of Government and Policy at Tel Aviv University. He is also Co-President of the Israeli Association for the Study of European Integration. His research interests include international political economy, the political economy of the EU (in particular the single currency and EU-Israeli relations) and international institutions and governance structures.

These figures do not appear to be indexed against real inflation and the massive increase of money supply engineered by international financial shenanigans and national and EU subsidisation of almost every field of productive/commercial activity,not least through taxation law which makes it exceedingly easy to borrow and invest at little after-tax cost.Nor do they take into account any natural increase in trade which would have occurred regardless,nor does it include-subtract churning and fiddling of the books.It looks like the proverbial statistics.There is a huge amount of hidden artificial pump-priming involved in national and international consumer,finance,commercial and production activity.It is,from an economic point of view,a house of cards built to effect continuous artificial economic growth and an infinite expansion of money supply to enable the technocrats and their gravy train merchants,the high-finance operators and the multinational corporates to go on creaming off as much as possible.They will continue to do so until Europe is destroyed or the people of Europe regain control over their own affairs.

@Jacob Some of these comments are extremely wide of the mark. You’ve stated here that the estimate doesn’t “take into account any natural increase in trade which would have occurred regardless”, but almost every mainstream study of the effects of currency unions uses control groups to account for precisely this effect.

We can certainly argue about the correct way to account for it, but to accuse the author of ignoring the issue completely – when there’s actually a sizeable chunk of text dedicated to this subject in the paper he’s linked to – is oddly dismissive. I would suggest actually reading the full account of the methodology in his paper before launching into a lengthy comment about why it’s wrong.

Let us agree that I have a different perspective on this and related issues.I am indeed dismissive of academic methodology if it confirms research which is written to support a political project such as the EU.For the life of me,I cannot see that the control groups’ performance of trade with other countries has any bearing on my argument against the thrust of the blog and the statistics which back it up.Say,Switzerland is not one of the Eurozone countries.Would you argue it has suffered from not being in a currency union?

Methodology apart,I maintain international trade does not of itself constitute a benefit for the citizenry overall of the nation-states in question.There is no doubt,somewhere,a curve of increasing and decreasing benefits for a national economy associated with increasing/decreasing international trade.Obviously,a currency union would increase trade between the member countries in statistical terms.So,on that score I have been less than precise.However,I see no reason why trade within countries cannot grow naturally,or that countries cannot increase trade with countries outside the currency union they are member of.If international trade of the countries in the control group does not increase as much as that between those in a(newly formed?) currency union,why would that invalidate my arguments against the worth,to the people of the countries in question,of a statistical increase in inter-currency union countries’ trade?Did you not get my drift?

In fact,some questions could be dealt with by the experts to clear some possible confusion.If,say,Germany were to export cars to Spain,paid for by the Bundesbank,would that constitute intra-currency union countries trade for the purposes of the statistical analysis which we are here to believe because it was modeled on new,very complicated programs on uber-extra powerful computers?Then,there is Greece and the matter of imports and exports of goods,services and money.Countries outside of the Eurozone are likely to have had bonus trade as a consequence of the funny money goings on in Greece all these years.The luxury yacht builders and brokers,not to mention banking in taxhavens around the world,have done very well,one should think.Yet,someone is paying for this,will be paying for this.People on basic wages who have no say in the matter,whose savings are taxed and inflated out of existence,whose assets are taxed on inflated values again and again.Rates up,taxes up,prices up,extra charges left,right and centre,privatisation of community assets/essential services,wages stable or going down if we consider the erosion of working conditions and increasing hours,redundancies,going through the hoops to get unemployment benefits.

Of course,the people employed to sell the message to the public have to go on trying to make the system believable,their jobs and pensions depend on it.Increasingly,it is Kafkaesquery on stilts.The longer it goes on,the longer the stilts.When,not if,it falls over it will be quite a sight,but the technocrats and their henchmen will be cooling their heels in buckets of champagne,in Bermuda,the Cook Islands or somewhere other than where they cooked up this mess.

@Jacob Let’s be very clear about this, you’ve written a lengthy comment criticising the methodology of the study above when you clearly haven’t actually read the methodology in the first place. It doesn’t matter what your wider perspective about the EU is, you can’t dismiss studies on methodological grounds simply because you don’t like their conclusions. That’s a complete nonsense and has no place in an academic discussion.

As for the wider points being raised here, this isn’t a normative article about whether international trade benefits citizens or not. It’s a technical article about how you measure the effect of the euro on trade. On that count it’s an open debate – depending on how you construct control groups the result will vary. If you have any methodological insights here then I’m sure they’ll be very welcome.

Regardless of what our view is on that issue, however, we’re talking about percentages, not principles. Your second sentence here seems to imply that you’re dismissive of any piece of academic research which leads to a pro-EU conclusion – I seriously hope that isn’t what you actually mean.

Yes Gordon,I thought is was clear that my comments were not academic,even though I dare comment on academic methodology.My comments are,lets say,philosophical.I have no compunction whatever criticising or upbraiding academics philosophically for studies which are theoretical or,in this case,academic.This blog in question,of which you say I have not studied the methodology(No,I read the blog and took it from there),are studies and computer programs run to effect a certain outcome,or perhaps not.In this case I determined philosophically that the effect of publishing it would have a political repercussion to the extent of influencing people who support,for whatever reason,the kind of money-merry-go-round which we have seen published in the media in latter years,but which came to my notice decades ago.I think these studies have an influence on political decisions in many ways,even if the public does not get to read them.For ever and the day academic studies are referred to when pressure is put upon the voters to accept policies,economic or otherwise,which many people from experience know are frauds,rackets and scams.

As to not trusting studies which appear to have a result which I may object to,it all depends whether it makes sense to me or not.So we are talking percentages here.I have made it clear that I take umbrage at academic studies which give a certain impression which is not warranted.Not all trade is equal.You might say that the study was about the statistics,nothing else.The methodology has to save the day.The methodology must be examined and found wanting if anyone wishes to criticise this study academically.Else one is perhaps not qualified to comment,or comment critically.If I had said that I thought what a marvellous study it was it would have been fine.Well,Despite the fact that my knowledge of these and other matters is,and has been for decades,greatly augmented by studies,theses,articles and books published by academics,which I duly and wholeheartedly acknowledge and appreciate,fully aware of the hard work and dedication these people have offered in the service,I nevertheless have long come to the conclusion that the academic world has come to be increasingly corrupted.A lot of studies are academic fairy floss,in my opinion.A lot of people more knowledgeable than me happen to agree.Perhaps I read the wrong books for your liking.May I recommend a few.The Trillion Dollar Conspiracy,Babylon’s Banksters,The New Few.

You keep mentioning methodology.I think you are missing something in this our day and age in the West.I have been following what is going on for years.I have put two and two together.I think I can,sometimes,smell academic bull from ten miles away.This is one such occasion.I would hate to do without academics in our world altogether,but if the majority make a meal of it to the extent that thinking people stop trusting academics,the real world will beat academics any day.I hope you can see my point.

Everyone has a right to comment on academic work, but it’s not legitimate to rubbish a study on the basis of non-existent methodological flaws simply because it suits your wider worldview. Especially when you criticise it for ignoring something that is actually dealt with in depth. The outline of the methodology is linked to in the paragraph above the first chart. If you don’t have the necessary subscription I would be happy to send you a copy of this.

As for the philosophical approach, as far as I understand it what you’re implying here is that it’s permissible to write off a study like this not because it’s demonstrably wrong, but on the grounds that it might have some political ramifications you disapprove of. In other words, you are (presumably) anti-euro/anti-EU, this study is giving a somewhat pro-euro conclusion, so you’re entitled to attack it to prevent it doing any wider damage to people who might base a decision on it. This seemingly isn’t evidence based, but more of an instinctual ability to “smell academic bull from ten miles away”.

I completely appreciate that it’s difficult for ordinary citizens to critique academic studies. That’s the nature of complex subjects and blogs like this are presumably a way to try and bring some of that research to a general audience in an accessible way. That doesn’t mean, however, that we can simply dismiss detailed studies on the basis of our own political persuasion.

Thanks Gordon.I will not refuse to start reading the methodology which you insist I should read in order to be credible,but more about that later.You claim I criticised the study on methodology.I would have rubbished the study on non-existent methodological flaws-your interpretation.I said what I said.I reread my first comment.I have also explained my philosophical position to a certain extent,already.You have indeed read the methodology,I trust.Instead of insisting that I too read it,you could have given me some specific examples to say where I was wrong specifically in relation the the methodology in question.Say,exports from Germany to Spain paid for by the Bundesbank.You ignored that.Financial shenanigans,is that part of the trade included in the statistics in question?You could have said straight off that that was excluded or accounted for in the methodology.No,you insist I must read the methodology.Well,I have been around for forty years as an adult,in Europe and Australasia(Oz-NZ).I have read a methodology for forty years,covering the whole wide world,although my life and travels and travails have been in the West-A methodology of which you seem to have a scant inkling.Maybe I am not so ordinary a citizen as we think,who knows?

However,I liken the academic world in the West to the Roman Catholic priesthood of,say,about the mid-sixteenth century.Those in theoretical economics,statistical studies,mainstream economics,academic economists and the like I deem on a par with what we know would say are the Jesuits.Not all bad fellows,sure.I have a very good friend who teaches financial analytical mathematics at uni,which is not unrelated to the subject under discussion.Now,I don’t consider myself a Luther,not quite.I have been somewhat critical of the Roman Catholic Church at times.Yet,I can’t read Latin,Old Greek and Hebrew.Aramaic is even more foreign to me.Yet I dare criticise Western priests,popes even,prelates certainly,without being forced to read up on the Bible.Back to today’s academicians.

You may be an academic.You are certainly obsessed with methodology,academic methodology.Rather than tell me where I went wrong specifically in relation to the methodology which I had/have as yet not read,you keep on insisting I must read it because I have rubbishing the study on the basis of the methodology which I have not read.I made comments in general and specific which you have ignored,by and large,because you had determined for yourself,from the evidence,of course,being methodical,that I had not read the methodology.Hence,rather than debate the issue on the level of an ordinary citizen,you insist I must read the methodology.Before I belabour this point some more,an inter alia.I think academics of a specific and more general nature in the West will find,in the near future or somewhat later,that ordinary citizens take into account and are familiar with a methodology which most academics have no interest in as yet.There are forces between heaven and earth which constitute a methodology of vast superior finesse than that of method-obsessed academics doing studies with complicated computer programs and very,very powerful computers.Are you supposing I should also study the methodology of the computer programming in question and the computer system itself that were used in the study in question.If not,why not?The programming and the computers are essential,and,indeed,deemed very important.Otherwise,why would it be stressed that very powerful computers were used.Come on,Gordon.the academic world in the increasingly decadent and corrupt West has come,in many instances,to be like a bunch of carpet-baggers selling academic spin.If we don’t believe it,just read the methodology.Which brings me back to intuition which you have no truck with.Unfortunately,as I mentioned,as you passed by,the methodology of all academics taken together is known by its fruit,the which we have been experiencing over the years.Can you understand that ordinary citizens get sceptical,dismissive even,when academics try to pull the wool over people’s eyes collectively?There are other point I made which you did not pick up.Perhaps I was not specific enough.Trade as far as statistics is concerned is neither here nor there.It will advantage some and disadvantage others.We are led to believe that without the currency union trade would have been less.Read the methodology,you say.I am referring to an economy not dominated by federalising technocrats.I am imagining trade within nation-states and between nation-states which may have different currencies.So,in fact,I would argue the point regardless the methodology you refer to-most unacademic,yes.Now,do send me the methodology in question.I will have a look at it.email:jacob@mystorium.com or via the lse moderator.