Recent opinion polls in the Netherlands have shown strong support among Dutch voters for Geert Wilders’ radical right Freedom Party (PVV). Ahead of the European Parliament elections in May, Stijn van Kessel assesses what a victory for the PVV would mean for the Netherlands’ EU membership. He argues that although current polls suggest the PVV will gain the largest number of seats in the country, this does not necessarily signal that Dutch voters support leaving the EU.

Recent opinion polls in the Netherlands have shown strong support among Dutch voters for Geert Wilders’ radical right Freedom Party (PVV). Ahead of the European Parliament elections in May, Stijn van Kessel assesses what a victory for the PVV would mean for the Netherlands’ EU membership. He argues that although current polls suggest the PVV will gain the largest number of seats in the country, this does not necessarily signal that Dutch voters support leaving the EU.

As in 2009, when it won 17 per cent of the vote, the populist radical right Freedom Party (Partij voor de Vrijheid, PVV) of Geert Wilders is expected to perform well in the upcoming European Parliament (EP) elections in May. Even though the electorate’s pessimism concerning the effects of the Eurocrisis and wariness about deeper European integration probably contribute to the PVV’s electoral performance, the results should in all likelihood be analysed primarily as outcomes of a ‘second order’ election. It is questionable, furthermore, whether Geert Wilders’ unequivocal pleas to end Dutch EU-membership will ever bear much electoral fruit.

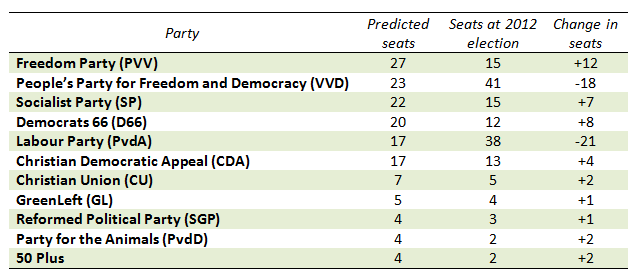

Unlike various other Dutch right-wing populist contenders in the past, Geert Wilders’ Freedom party has proven to be very resilient. Despite a loss in the Dutch parliamentary election of 2012 (in which it received 10.1 per cent of the vote, compared with 15.5 per cent in 2010) and intra-party conflicts leading to the dismissal or defection of several MPs, the PVV tops recent opinion polls. As the Table below shows, if a national election were to be held today the PVV would be predicted to gain 12 seats on its showing in the 2012 elections, and be the largest party in the Dutch parliament.

Table: Seat projections for Dutch House of Representatives based on opinion poll average (February 2014)

Note: Elections to the House of Representatives use a national party list form of proportional representation. It is therefore common for opinion polls to articulate results as seat projections rather than vote shares. The figures in the table stem from De Peilingwijzer of political scientist Tom Louwerse, who calculates an average of the four political polls that are held regularly in the Netherlands: TNS NIPO, Peil.nl (Maurice de Hond), de Politieke Barometer (Ipsos Synovate) and De Stemming (EenVandaag). Source: Nederlandse Omroep Stichting.

Wilders will be the most vocal opponent of European integration in the upcoming EP election, as was the case in the past campaigns for both European and national elections. The difference with five years ago is that Wilders has sharpened his opposition to ‘Europe’ and now favours a Dutch withdrawal from the EU. His EU-related discourse radicalised in the run up to the 2012 parliamentary election, and European integration also became a more prominent issue for the Freedom Party. In its manifesto from 2012 (titled ‘Their Brussels, our Netherlands’), the party railed against the ‘unelected multi-culti Eurocrats’, and highlighted the socio-cultural and socio-economic threats of the sovereignty-undermining ‘holy Great-European project’. At the same time, Dutch politicians were blamed for slavishly complying with the ‘diktats from Brussels’ and handing out money to untrustworthy countries such as Greece and Romania.

With more than three months to go to the EP election, Wilders has already started a new tirade against Brussels – for instance with short anti-EU videos distributed through his party’s online newsletter. On the 6th of February, Wilders attracted attention when results were presented of a PVV-initiated study by the British consultancy Capital Economics about the economic consequences of a Dutch withdrawal from the EU. Perhaps rather unsurprisingly in view of the consultancy’s reputation as a ‘leading voice for Eurozone break-up’, but to the delight of Wilders, the report argued that a ‘NExit’ was likely to benefit the Dutch economy.

Wilders has thus set the tone for the upcoming European election campaign – which is actually preceded by local elections in March – leaving his ‘Euroreject’ position unrivalled. The radical left Socialist Party has been wary of deeper integration and intra-EU labour migration, and criticised the presumed neo-liberal character of the EU. Yet the party also acknowledges the benefits of ‘Europe’ in terms of peace, security and prosperity, and supported stricter control over national budgets and the financial sector by the European Central Bank (ECB).

The traditionally (or previously) dominant pro-European mainstream parties – the Liberals (VVD), Labour (PvdA) and the Christian Democrats (CDA) – are likely to speak of the general benefits of EU membership, although they will probably do their best to avoid sounding too Europhile by criticising the alleged failures of the EU and conveying their reluctance to sacrifice national sovereignty. The most pro-European stance will be taken by the two culturally liberal parties GreenLeft (GL) and Democrats 66 (D66), the traditional antagonists of Wilders’ Freedom Party.

At first sight, the Eurorejection of the Freedom Party may seem a risky strategy; Eurobarometer surveys throughout recent decades have shown that a great majority of the Dutch have supported EU membership and considered it to be beneficial to the Netherlands. Even though these figures have declined since the second half of the 1990s, opinions toward EU membership remained relatively positive, certainly in comparison with traditionally Eurosceptic countries such as the UK, or crisis-struck countries such as Greece and Portugal, where support levels for EU membership have declined toward the end of the 2000s. Following the results of the Standard Eurobarometer from Spring 2013, 71 per cent of the Dutch disagreed with the statement that the Netherlands could better face the future outside the EU (compared with an average EU-wide figure of 56 per cent).

One should nevertheless be careful not to read too much into these figures. Even though most Dutch people remain convinced that the Netherlands is better off inside the EU, this does not mean that they are uncritical about the way it is designed or functioning. This was for instance shown by the popular rejection of the Constitutional Treaty in a referendum in 2005 (61.5 per cent of those who turned out voted against).

What is more, the Spring 2013 Eurobarometer results also showed that 58 per cent of the Dutch tended to distrust the EU (while only 37 per cent expressed trust), and that more people had a negative (34 per cent) than a positive (27 per cent) image of the EU – the latter figures denoting above average negativity compared with the EU27-mean. An October 2012 opinion poll conducted for the news show Eén Vandaag furthermore showed that only a quarter of the respondents desired shifting more responsibilities to the EU, while 55 per cent thought that giving the EU more influence over nation states’ budgets in response to the crisis was a bad idea (against 33 per cent who thought the opposite).

Judging from these figures, there is certainly room in Dutch politics for parties with an outspoken Eurosceptic message. Bearing in mind the suspicion among the population about the EU and further integration, it is also no surprise that most essentially pro-European parties want to downplay their enthusiasm for European cooperation and shy away from presenting a clear vision about the future of Europe. The EP election campaign will probably again revolve around a crude and abstract ‘more vs. less Brussels’ debate, with Wilders now at least providing a clear choice.

Yet a good result for Wilders in the EP election will reflect primarily the fortunes of his party as it stands in the national context, rather than the electorate’s rejection of EU membership. The results are likely to confirm the ‘second order’ character of European elections, where (smaller) opposition parties do well and governing parties – at the height of their unpopularity – are punished.

Even though the campaign will largely be centered on the theme of European integration, and even if many voters will use the EP election to express their apprehension about European integration, it is questionable whether the results are very indicative of the intensity of Eurosceptic sentiments among the Dutch electorate and the salience of EU-related issues. It is telling that – though there were also other reasons for the party’s loss – the Freedom Party did not perform very well in the parliamentary election of 2012 after having placed so much emphasis on the EU theme. In first order national elections, which are (still) primarily about more salient domestic issues, a platform primarily built around an anti-EU appeal is not likely to attract a great number of voters.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1lq4kSV

_________________________________

Stijn van Kessel – Loughborough University

Stijn van Kessel – Loughborough University

Stijn van Kessel is Lecturer in Politics at Loughborough University and currently based at the Institut für Deutsches und Internationales Parteienrecht und Parteienforschung (PRuF) at the Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf. His postdoctoral fellowship at the PRuF is funded by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. His research interests include populism and political radicalism, party competition and elections, developments in European party systems and related questions of democratic legitimacy.

I can agree with most of the conclusions, however you seem to go way too easily over some not so convenient stuff.

-Wilders had a poll done at the same time as the report it isnot even mentioned. And I didnot see any indication that it was biased or the questions were leading to certain desired answers. The poll indicated that the Dutch would want to leave the EU (the EU not the Euro mind) IF it would get them extra jobs and that kind of stuff.

So a clear conditionality (of course exploited by your Geert by trying to portrait it as much as possible as unconditional) but nevertheless.

It also indicated that your people were in considerable majority fed up with certain parts (apparently essential ones seen the Swiss discussion) of EU policies. Looked like a clear indication of a further move/trend into the direction of Eurosceptism to me tbo.

The report itself clearly has some rubbish in it. However I have not seen any proper technical remark from anyone of the anti-Wildersfront (including yourself). Not on the weak points and not on the stronger ones as well.

Some of the points do really make sense.

And why try outflank Wilders by using populists tactics especially on what is supposed to be an academic blog. At least Wilders comes up with a report. Who is the populist here?

Simply looks like, on some of the topics, traditional politics is trying simply to avoid a proper discussion. Incl yourself again, not strictly politician of course, but clearly having an antipathy against Wilders (understandable btw from a personal pov, but hardly an academic approach).

I do btw fully agree that a Wilders victory will not jeopardize the Dutch EU membership. But things are clearly moving in the wrong direction (from an EU pov) and to be honest I donot see in the near future that trend being stopped. The reasons for it, are simply still present and very likely will remain present in the near and med long future at least.

Likely the Dutch discussion will go roughly in the same way as you write in your article, but that is politics (and Wilders will undoubtedly have some aces in his sleeves as well), this is however an academic blog.

2 points that would benefit from some more attention btw. Several other political parties are in degree Euro-sceptic/Euro-critical this is not clearly mentioned.

Hardly anybody else, may be with the exception of your Christian Taliban, will be pro-exit but policies might change even likley will be changed because of electoral pressure These parties plus Wilders are rapidly approaching the 50%.

Another point is that the political parties (traditional government parties, but mainly now the 2 government parties) that are attacked by Wilders, but also by the other Euro-critical parties look clearly to react on the positive poll results of these critical parties. By moving themselves into a more Euro-critical direction.

So exit hard to see, but more Euro-critical policies very likely.

To get back on my earlier remark.

Your sort of remarks is basically the standard response to Wilders. And to be honest one of the best I have seen of that sort.

However it is simply not working, the guy in the mean time has become the largest party in the polls. Trend Wilders positive certainly the longer term one. Add the rise of other Euro-critical parties and it is clear, to me at least, that the present Dutch EU-policies are simply unsustainable. Likely a combination of insufficient platform to start with, crap (and that is still positive) selling, and a self created general credibility crisis in politics. And simply nothing seems to improve even after a decade or so it is simply when Wilders shows up push the repeat button.

-New policies for which there is no real platform.

-Giving a lot of people the impression that it is pushed down their throats in the process;

-Spin on earlier policy disasters/failures that nobody buys;

-namecalling everybody that doesnot agree is a fascist or a racist (while that stopped working years ago as well);

-Remarks like here it is Wilders so it must be non sense (while it is clear that a lot of people are buying Wilders his message).

Just to name a few more important ones.

We are now at a stage where people like Wilders and LePen (see todays poll in France) can start wiping up the normal vote as this process just goes on and on and on. Fine job.

You simply need another approach and fast time is running out. We are now at Einstein’s Definition of Madness version 743.0 or so.