Alongside the European Parliament elections in May, Belgium will also hold simultaneous federal and regional elections. Régis Dandoy assesses the role of the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA) in the elections. The N-VA, which advocates the independence of Flanders from Belgium, emerged as the largest Belgian party in the 2010 federal elections, but the country endured 20 months of negotiations before a government was finally formed. He notes that with the N-VA likely to receive similar levels of support in 2014, lessons from the 2010 crisis will need to be taken on board if the same impasse between Flemish and Francophone parties is to be avoided.

Alongside the European Parliament elections in May, Belgium will also hold simultaneous federal and regional elections. Régis Dandoy assesses the role of the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA) in the elections. The N-VA, which advocates the independence of Flanders from Belgium, emerged as the largest Belgian party in the 2010 federal elections, but the country endured 20 months of negotiations before a government was finally formed. He notes that with the N-VA likely to receive similar levels of support in 2014, lessons from the 2010 crisis will need to be taken on board if the same impasse between Flemish and Francophone parties is to be avoided.

On 25 May 2014, Belgian citizens will participate in the European, federal, regional and community elections. These simultaneous elections have been named “the mother of all elections” as Belgian voters tend not to split their ticket. In other words, the party that loses these elections will probably remain in the opposition at all these policy levels for the next five years. But the central attention in these elections turns – once again – on the linguistic issue and the electoral performance of the Flemish nationalist party New Flemish Alliance (N-VA).

The Belgian linguistic conflict – that mainly comprises Flemish (Dutch-speaking) and French-speaking parties – is particularly salient at election times. Broadly speaking, Flemish citizens cannot vote for French-speaking parties and French-speaking citizens cannot vote for Flemish parties. As a result, the electoral system favours the polarisation of the campaign on each side of the linguistic border: parties will not be sanctioned by the voters if they unfairly “attack” the parties from the other community. Media also contribute to the polarisation of the parties during the campaign, as articles on the linguistic conflict are obviously more appealing than news on the obscure debates regarding the financing of social security.

Elections are also the ideal moment for parties to present their vision for the future of the Belgian state. With the renewed federal assembly comes the possibility of revising the Constitution and therefore the possibility to change the institutions and the set of rules that govern the relations between the two communities (the so-called linguistic laws). In their manifestos and electoral discourses, parties emphasise these aspects and present their “recipes” for the governance and the sustainability of the country. By definition, the positions of the N-VA on these issues have an important impact on the campaign, on both sides of the linguistic border. Parties and media scrutinise the priorities and the content of the manifesto of the Flemish nationalists as they will largely set the pace for the electoral campaign.

The N-VA is clearly on the rise. The party decided in September 2008 to leave the electoral alliance signed with the Christian-democrat party CD&V and to participate in the elections on its own. The first opinion polls indicated that the 5 per cent threshold used in Belgian elections could be an issue for the N-VA; yet, in the regional elections of 2009, the Flemish nationalist party obtained over 13 per cent of the votes in Flanders, far above the threshold. Together with the CD&V and the Socialist Party (sp.a), the N-VA entered the Flemish government.

The 2010 federal elections led to a “political earthquake” in Flanders: the N-VA obtained just over 28 per cent of the votes in Flanders and became Belgium’s largest party. Consequently the N-VA was associated to the talks for the government formation and the reform of the state structure. After almost a year and a half of political crisis, a new federal government was formed, leaving the Flemish nationalists in the opposition. In 2012, the N-VA participated to the 2012 local and provincial elections. The party once again obtained over 28 per cent of the votes in the Flemish provinces and entered several local governments. The party leader Bart De Wever became mayor of Flanders’ largest city, Antwerp.

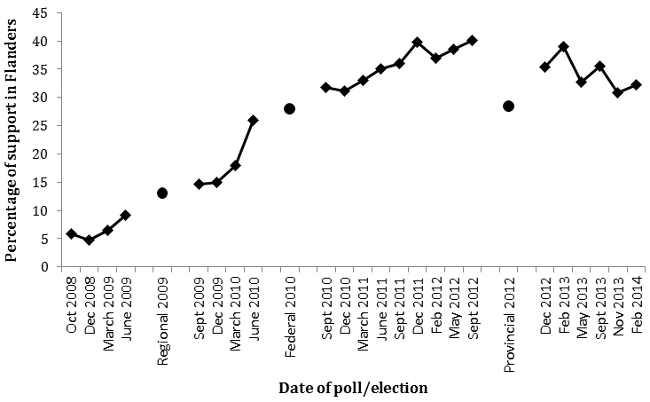

Yet, as the Chart below shows, the results of the party for the 2012 provincial elections do not match with opinion polls. Since September 2010, almost all opinion polls have given the N-VA over 30 per cent of vote intentions in Flanders, with the party even reaching 40 per cent in some polls. But all polling institutes confirm that the impressive and linear growth of the party’s popularity since 2008 has stopped and has even declined since the end of 2012. Most opinion polls now predict that in May 2014 the party will be likely to obtain electoral results very close to those obtained in 2010.

Chart: Vote share for N-VA in Flanders in opinion polls and elections since October 2008

Note: The chart combines results in opinion polls with the share of the votes received by the N-VA in regional, federal, and provincial elections. Opinion polls are from La Libre / RTBF.

The N-VA and Flemish independence

Compared to 2010, the N-VA has officially changed its position regarding the future of Belgium. The N-VA still wants independence for Flanders in the long term (as clearly mentioned in its statutes), but this demand for independence is no longer a priority for the party. This objective is even absent from the first drafts of its manifesto for the 2014 elections. The focus is rather on an intermediary step: confederalism. The notion of confederalism was already present in the previous manifestos of the party, but was emphasised to a much lesser extent.

Remarkably, these demands for an evolution of the Belgian federal structure into a confederation were in 2010 shared by the CD&V and the liberal party Open VLD. Recently, the Open VLD decided to give up its demands for a confederal Belgium and focus on socio-economic issues. The CD&V still believes in the virtues of confederalism, but now defends a so-called “positive confederalism” that would aim at preventing the split of Belgium.

But why would the N-VA give up its objective of an independent Flanders? The answer is quite simple: the party wants to give the image of a moderate nationalist party. This strategy relies on a double aim. First, the party does not want to scare voters that might be put off by radical proposals on the future of Belgium. Research indicates that only 12 to 15 per cent of Flemish voters want an independent Flanders, and recent opinion polls indicate that the party needs to attract new voters if it wants to be considered as the winner of the 2014 elections.

Second, the party does not want to scare the other parties as this would damage its appeal as a negotiating partner in government formations. As the formations of the next regional and national governments are likely to be linked (i.e. the same parties will be in power at both levels), exclusion from the negotiations would mean being relegated to the opposition for five long years at both policy levels. In 2010, the N-VA could adopt a more radical profile as the party was part of the Flemish regional government after the 2009 regional elections.

The 2014 elections

Altogether, the next regional and federal elections of May 2014 will presumably be similar to the 2010 elections. After the electoral shock of 2010, one should observe a stabilisation of the Flemish party system. With the exception of the extreme-left party PVDA, which is likely to obtain a few seats, there are no new parties emerging in Flanders. Opinion polls do not indicate large differences in vote shares for all established parties and suggest that the N-VA will again obtain about 28 per cent of the votes.

Unsurprisingly, the electoral campaign will be dominated by the polarising linguistic conflict between Flemish and French-speaking parties. Party positions on this issue have not changed much since the last elections. All French-speaking parties still oppose any further state reform and decentralisation while, in Flanders, the two largest parties – N-VA and CD&V – clearly demand a new round of reforms, leading to more autonomy for Flanders. The strategic moderation of the position of the N-VA regarding the independence of Flanders is only a façade and many observers state that the confederalism advocated by the nationalist party is very close to genuine separatism. We have to trust decision-makers in their capacity to learn from the long political crisis that emerged from the 2010 elections. Otherwise, Belgians are probably condemned to go through the same events.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1gu4nJU

_________________________________

Régis Dandoy

Régis Dandoy

Régis Dandoy is a Belgian political scientist and currently Prometeo Researcher at the Department for Political Studies at the FLACSO (Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales – Ecuador). He is also Research associate at the University of Brussels (ULB – Belgium) and the University of Louvain (UCL – Belgium).

Good overview: not easy to make such complex issues… easy. I would have question marks as to the use of the ‘easy’ “linguistic issue” concept. I would have preferred focusing on the “identity issue” and the regional right/left trends

First of all, to describe the rise of the N-VA to purely linguistic demands is rather dishonest. One should at least mention the influence of the francophone Parti Socialiste on Belgian poltics, the divide between centre-left politics in Wallonia and centre-right politics in Flanders is a much better explanation.

Secondly, “Flemish citizens cannot vote for French-speaking parties and French-speaking citizens cannot vote for Flemish parties” is simply not true, ANY poltical party may present itself to ANY constituency throughout the country.

Thirdly, the N-VA has consistently said it is not a ‘revolutionary’ party but rather an ‘evolutionary’ one, meaning that confederalism has always been put forward by the N-VA.

They will never ask for a referendum on Flemish independance.

Only because CD&V, OpenVLD and SP.a (Flemish socialists) have recently obscured what they mean by confederalism has the N-VA provided more details on what confederalism means to them.

N-VA’s congress last year unveiled what De Wever’s party means when they say they want a “confederalist model” for Belgium – essentially, it just stops one small step away from a complete separation, hollowing the Belgian state of nearly all its competences and submitting Brussels to the control of Flanders and Wallonia.

Having said that, following the 500+ days of political crisis of 2010-2011, it’s unlikely the same situation will repeat itself. After the last elections, the N-VA was in a position where they could make all sorts of demands and still be praised by their electorate for refusing Francophone proposals (as well as the painstaking work done by Vande Lanotte during the talks) – the tactic was essentially making as much of a fuss as possible to show that Belgium does not work. Four years later, the electorate will expect more professionalism and the N-VA is not willing to spend more years in the opposition, which implies swallowing their pride and accept that if a party joins the Belgian government, their job is not to undermine the integrity of the Belgian state.

According to the Belgian constitution the Belgian state is comprised of the different Regions and Communities. You can’t hollow out the Belgian state by transferring competences between different government levels WITHIN that state.

As to the 500+ days of political crisis : you can hardly blame N-VA for that, just have a look at http://bit.ly/1crYgJe , this graph clearly shows that both socialist parties, the PS and the SP.a share the burden of this long period. When, on October 17th 2011, the N-VA presented a written proposal it took the francophone parties less than 24 hours to reject it thus sidelining the N-VA and it still took them till December 6th to get a new government….

Sorry, dates should be October 17th 2010 & December 6th 2011 respectively….