The Ukrainian Parliament has voted to remove the country’s president Viktor Yanukovych from office, with an arrest warrant also being issued over his role in the death of protesters last week. Javier Morales writes on the complexities of Ukrainian society, arguing that without acknowledging the country’s ethno-linguistic and cultural divisions we run the risk of underestimating the consequences of recent events. He writes that any new political leadership will need to take on board the interests of all citizens, including those in eastern and southern regions who have supported Yanukovych.

The Ukrainian Parliament has voted to remove the country’s president Viktor Yanukovych from office, with an arrest warrant also being issued over his role in the death of protesters last week. Javier Morales writes on the complexities of Ukrainian society, arguing that without acknowledging the country’s ethno-linguistic and cultural divisions we run the risk of underestimating the consequences of recent events. He writes that any new political leadership will need to take on board the interests of all citizens, including those in eastern and southern regions who have supported Yanukovych.

The images that we received from the protests in Ukraine, tragically marked by the high number of victims, do not properly reflect the complexity of the conflict. Although the overarching narrative is partly correct, we risk omitting other facts that present a much more contradictory reality – one that is far from the romanticism that is apparent to those who are looking toward the country for the first time.

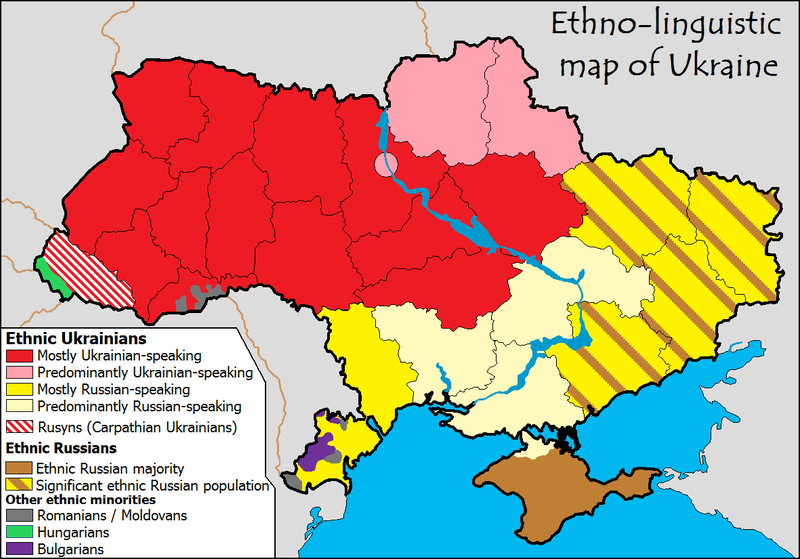

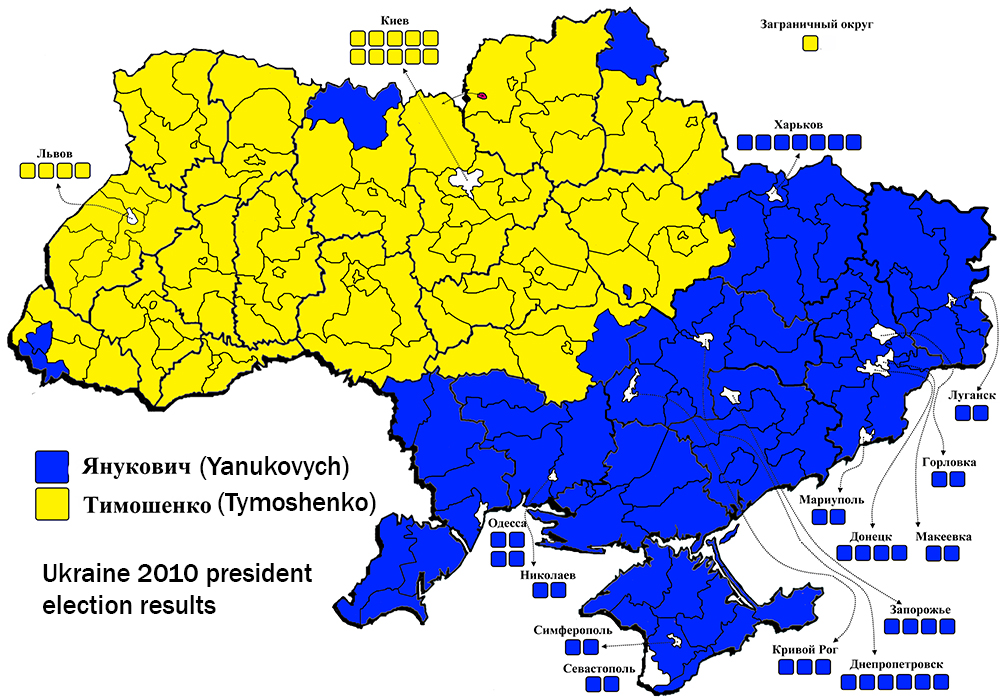

First, by focusing on the capital (the events at the Maidan square and the surrounding area) we obscure the substantial regional diversity in Ukraine, which is not represented in Kyiv. To summarise, we can describe the Ukrainian society as being divided between the western and central regions (including the capital), which identify the Ukrainian nation with the Ukrainian language and vote for the opposition parties leading the protests; and the eastern and southern regions, where the Russian-speaking population combine their Ukrainian identity with Russian culture, and most support President Yanukovych’s party. The geographic distribution of votes in the 2010 presidential election, shown in Figure 1, matches the ethno-linguistic divide in the country, shown in Figure 2, and is explained by it to a great extent.

Figure 1: Geographic distribution of votes in the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election

Source: Washington Post

Figure 2: Ethno-linguistic map of Ukraine

Source: Wikimedia Commons (Credit: Yerevanci; CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Source: Wikimedia Commons (Credit: Yerevanci; CC-BY-SA-3.0)

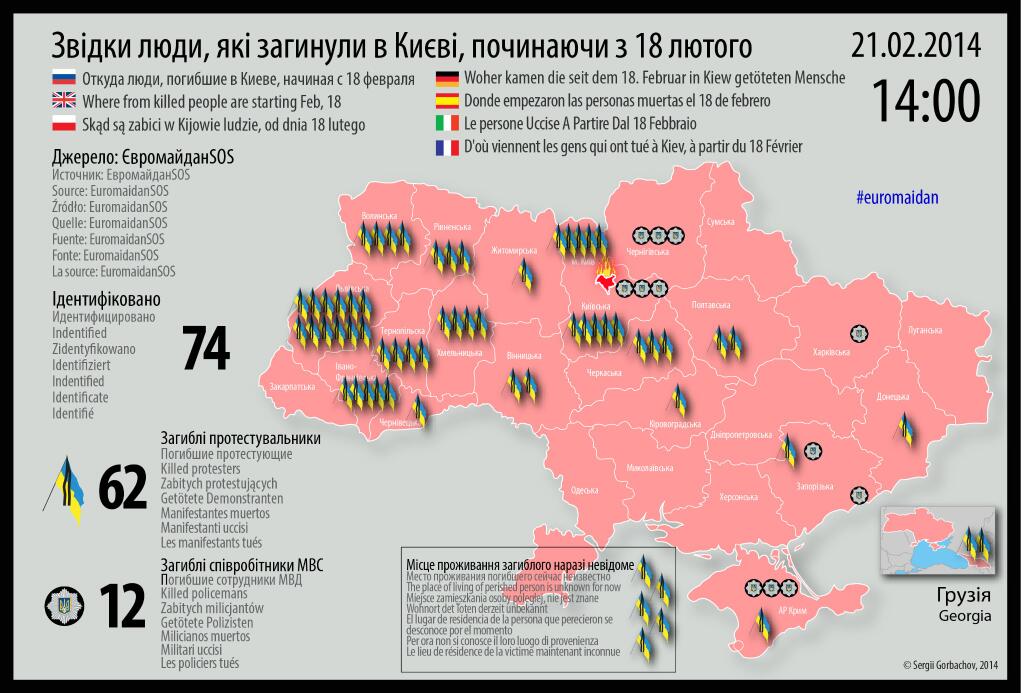

Although the protest movement has attracted demonstrators from outside Kyiv, and has also spread to other parts of Ukraine, the geographic divide remains. For example, the victims among the opposition (according to their own data, fig. 3) came from the western and central regions; while the police officers that were killed came from the centre and east.

Figure 3: Place of origin of individuals killed during the Ukraine protests

Note: Fatalities on the side of the protesters are shown by the Ukrainian flags, while fatalities on the side of the police/security forces are shown with the round badge. Source: Euromaidan

Note: Fatalities on the side of the protesters are shown by the Ukrainian flags, while fatalities on the side of the police/security forces are shown with the round badge. Source: Euromaidan

This polarisation does not allow us to speak of a united nation against the government. A significant proportion of Ukrainian society opposes the Maidan’s demands, with 70 per cent in eastern regions and 80 per cent in southern regions against it, compared to only 20 per cent in the west. However, dissatisfaction with Yanukovych’s management of the crisis has also risen among his own supporters. Yanukovych is an undoubtedly corrupt politician with little inclination to dialogue – as a young man he was sent to Soviet prisons twice for theft and assault. Yet, in spite of his responsibility for the repression, he was still a democratically-elected president that obtained 49 per cent of the votes only four years ago, in an election that was deemed free and fair by international observers.

For people in the eastern part of the country, his Party of Regions represents the protection of their interest vis-à-vis those in the west – who, in their opinion, are discriminating against them because of their ethno-linguistic differences. Any political solution to the conflict should necessarily take the views of this part of Ukrainian society into account or accept the risk of fracturing the country for good.

Within the opposition that is now taking power, we find several actors with contradictory objectives. As we know, the protest, which renamed Kyiv’s Independence Square as the ‘Euromaidan’, was sparked by the president’s decision not to sign an Association Agreement with the EU. This was interpreted by many citizens as the end to their aspirations of prosperity as future EU members, although full EU membership had not been offered at any time by Brussels. The first mobilisation represented an indignant society against the rampant corruption of their government, allied with business oligarchs to exploit a country in serious economic crisis.

Even then, it was evident that the Maidan was a very heterogeneous movement: the political parties that led the demonstrations represented ideological views ranging from Fatherland or UDAR in the centre-right, to the ultranationalism of Freedom (Svoboda). While the leaders of the first two parties, Arseniy Yatsenyuk and former boxing champion Vitali Klitschko, could be seen by the US and Europe as a democratic alternative; Svoboda’s leader Oleh Tyahnybok was associated with a xenophobic discourse that clearly contradicted EU values.

The Maidan’s more recent turn to violence was the result of Yanukovych’s authoritarian decision to restrict the right to public protest, using new legislation that was later cancelled, but at the time convinced many demonstrators that there was no point in sticking to peaceful action. In this new climate, new groups started rising: the far-right Right Sector (Praviy Sektor) organised the Maidan’s paramilitary ‘self-defence’ unit, while its leaders gave interviews to Western journalists declaring that they were armed and planning to take power by force through a nationalist revolution that would eliminate all Russian influence in the country. Football hooligans, known as ultras, also joined the protest as protection against the titushki: the government-sponsored thugs that helped the police in the repression.

This ultranationalist minority negatively influenced the protest: urban guerrilla tactics like petrol bombs were widespread and a few demonstrators were seen using firearms. On the other side, indiscriminate killings by police snipers caused many civilian casualties and created an ideal setting for radicalisation, uniting the protesters in the face of tragedy and encouraging them to keep fighting. At the same time, the opposition parties’ influence in the Maidan decreased, as the movement started to follow its own dynamics rather than orders from above.

In the short term, the possible future scenarios are highly volatile. The agreement reached through the mediation of several European ministers became obsolete the day after it was signed: Yanukovych and other high-ranking officials fled the capital, while the opposition’s deputies started to pass new legislation in parliament. The greatest risk is that none of these actors – not even the EU or Russia, whose influence on the ground is limited – will manage to fully control the situation. Even if Klitschko, Yatsenyuk or the recently freed Yulia Tymoshenko, who is apparently returning to active politics despite her health problems, became the new leader of the country, this would not necessarily be accepted by all protesters. Many, including the far-right minority, do not feel represented by politicians who they also perceive as corrupt and distant from their fight in the streets.

With regard to the Russian-speaking regions in the east and south, if they feel marginalised from the decision-making process by the new authorities they could start their own protest movement, or even take steps towards their independence. A future of entrenched civil conflict would, unfortunately, be much closer to a tragedy for the whole country than to an epic victory for one side.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: Photo by Yehor Milohrodskyi on Unsplash. This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/NrmibN

_________________________________

Javier Morales – Universidad Europea, Madrid

Javier Morales – Universidad Europea, Madrid

Javier Morales is a Lecturer in International Relations at Universidad Europea (Madrid), researching international security and Russia’s foreign policy. He is a co-editor of the Eurasianet.es blog and collaborates with the foreign policy observatory at Fundación Alternativas. He tweets @jmoraleshdez

Excellent article, keep up the good work !