The Crimean parliament has voted in favour of the region seceding from Ukraine and joining the Russian Federation. If Russia agrees to this request, it is expected that a referendum will be held in Crimea on 16 March. Tatyana Malyarenko and Stefan Wolff assess opinion polling data in Crimea and write on the potential options for the region’s future. They argue that finding an interim solution which allows the situation to stabilise may be a useful way forward before making long-term decisions on Crimea’s status.

The Crimean parliament has voted in favour of the region seceding from Ukraine and joining the Russian Federation. If Russia agrees to this request, it is expected that a referendum will be held in Crimea on 16 March. Tatyana Malyarenko and Stefan Wolff assess opinion polling data in Crimea and write on the potential options for the region’s future. They argue that finding an interim solution which allows the situation to stabilise may be a useful way forward before making long-term decisions on Crimea’s status.

The situation in Ukraine is still highly volatile, especially in relation to Crimea and continuing uncertainty about Russia’s intentions. But there is a need to consider what a longer-term solution might look like in light of the different demands being made.

In Western capitals there has been a lot of talk, but less walk, about allowing the people of Ukraine to decide their future free from any outside interference. Western Europe in particular, it seems, is firmly focused on protecting its fragile economic recovery. Yet, not only is much of this talk informed by an assumption that Western promotion of democracy in Ukraine does not fall into the category of outside interference (while Russian actions, in contrast, do) but there is also very little in terms of hard facts to inform speculation about the motivation of people in Crimea and elsewhere in Ukraine.

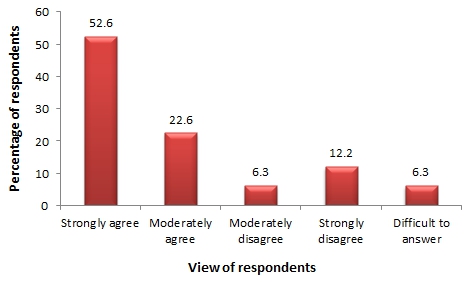

Opinion polls carried out over the years tell a very interesting story. According to data from the Razumkov Centre, the share of the population in Crimea that view themselves as patriots of Ukraine has been around 9 per cent, which is unsurprising given that, as shown in Chart 1 below, 75 per cent consider themselves to be subject to “Ukrainianisation”.

Chart 1: Responses in Crimea to the question: “Do you agree that the Crimean population has undergone ‘forced Ukrainisation’?”

Source: Razumkov Centre

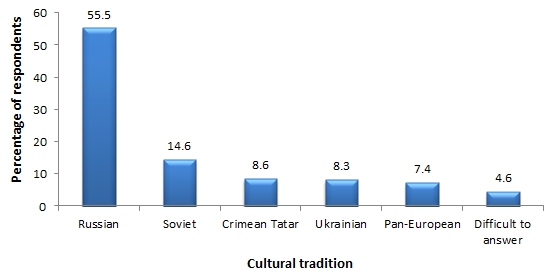

As shown in Chart 2, in an alternative poll conducted by the Razumkov Centre, 55.5 per cent of respondents stated that they associated themselves with the Russian ‘cultural tradition’, while 8.3 per cent associated themselves with the Ukrainian ‘cultural tradition’, and 7.4 per cent with a pan-European cultural tradition.

Chart 2: Responses in Crimea to the question: “With which cultural tradition do you associate yourself?”

Source: Razumkov Centre

Polls from the same organisation also indicate that some 79 per cent of people are in favour of a union with Russia and Belarus. A different poll carried out between 8 and 18 February, while allowing for a significant margin of error, finds 41 per cent of Crimea’s residents in favour of unification with Russia, compared to 33 per cent in Donetsk and 24 per cent in Lugansk (the other two major pro-Russian regions in Ukraine), and 24 per cent in Odessa, 6 per cent in Kiev, and virtually no support in the western regions.

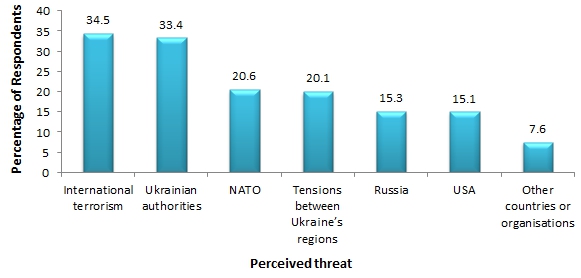

Data from 2011 also show that 51 per cent of Crimean residents viewed NATO as an important security threat to Ukraine, whereas the nationwide perception was much lower with 21 per cent, and even lower in central Ukraine (13.1 per cent) and western Ukraine (10 per cent). Interestingly, though, the perception of Russia as a threat was almost the same with 15 per cent of Ukrainians in general and 13 per cent of Crimean residents seeing Russia in this way. Finally, the view of the government in Kiev (at the time run by Mr Yanukovych) as a threat shows significant divergence of opinion: 33.4 per cent of Ukrainians in general against 13 per cent of Crimean residents. Chart 3 below shows the figures for Ukraine as a whole.

Chart 3: Percentage of Ukrainian citizens who identify actors/scenarios as ‘threats’ (2011)

Note: The figures show the percentage of Ukrainian citizens that viewed each actor/scenario as a threat. Each threat is treated individually so it was possible for the same respondent to indicate that they thought several or all of the topics listed were threats. Source: Razumkov Centre

Two interesting aspects emerge from this data. First, despite long-standing high support in Crimea for a union with Russia, up until very recently this has not translated into a mass movement actively seeking Crimea’s separation from Ukraine. Second, while triggered by the competition between the EU and Russia over influence in and on Ukraine, anti-Russian sentiment in Ukraine as a whole has not so far been a decisive political rallying cry, rather protests in the Maidan since last year were initially primarily directed against the government of President Yanukovych and as much about corruption and a lack of human rights and the rule of law than about his allegiance to Russia.

Three major factors account for stability in Crimea and in relations between Simferopol and Kiev and Moscow and Kiev, respectively: the status of Crimea’s autonomy in Ukraine; the status of the Russian language in Crimea (where it is common to all residents) and Ukraine; and the security of Russia’s navy base, which is strategically important to Russia, and seen as a “guarantee” for the peninsula’s status, as well as a major economic factor. A threat to any, let alone all, of these factors cannot but seriously destabilise the situation within Crimea, Ukraine, and between Russia and Ukraine.

The Euromaidan revolution in 2013/14, similar to the Orange revolution almost a decade earlier, created a strong sense of insecurity in Crimea, in particular, regarding the status of autonomy and the Russian language. This was not unfounded as the new majority in the Ukrainian parliament annulled the law that gave a number of privileges to the Russian language (as co-equal to Ukrainian) and made statements to the effect that Crimea’s status as an autonomous republic in Ukraine may be abolished.

The pro-Russian Crimean political elites, in response to these events, took steps which they saw as logical for preserving the status quo and protecting the Republic’s interests. The Crimean parliament passed a resolution announcing their intention to restore the 1992 constitution, subsequently abolished by the Ukrainian parliament, according to which Crimea and Ukraine were a confederation and to hold a referendum on this issue in Crimea.

Russia, clearly fearful of being challenged by the new Ukrainian government over its navy base and feeling humiliated by the prospect of ‘losing’ Ukraine to the EU after all, took these threats as a welcome pretext to come to the “rescue” of its co-ethnics and compatriots in Crimea. Moreover, the apparent weakness of the Ukrainian state created a relatively low-cost opportunity for Russia to strengthen its position in the region relative to both the West and Ukraine.

This, in turn, internationalised the political and constitutional dispute in Ukraine and led to the escalation we have witnessed over the past week with Russia conducting a low-intensity operation that has strengthened its grip on Crimea and has widespread support among one faction of local residents. Yet, it also has drawn the ire of pro-Ukrainian forces in Crimea, increased anti-Russian sentiment on mainland Ukraine, and caused a serious rift in relations between Russia and the West.

While we cannot understand the developments in Crimea outside the Ukrainian, Ukrainian-Russian, and Russian-Western contexts, it is equally clear that Crimea has evolved into the centrepiece of this complex and multi-layered conflict. No sustainable de-escalation and stabilisation will be possible without finding a way forward on the Crimean issue that addresses the different needs and demands of the parties involved: the different political forces in Crimea, as well as the governments of Ukraine and Russia.

The first step, of course, is to create a process of engagement between them. This may require some additional confidence-building measures, which could include a restoration in some form of the 21 February Agreement. A necessary second step will involve considering the substance of any potential arrangements that could satisfy different parties’ interests to such a degree that they would commit to a deal that would offer them greater returns than any alternative confrontational course.

Given the precarious legal and constitutional framework on which the current status of Crimea has been built since the Soviet period, a purely legal “solution” taking recourse to past institutional arrangements is unlikely to be possible or even desirable. What is required is first and foremost a political decision and a commitment to put it on a sound legal and constitutionally as well as internationally agreed basis.

While arrangements that protect the different communities in Crimea, the peninsula’s status within Ukraine, and the Russian navy base are not too difficult to imagine, the current intensity of tensions, high levels of mutual recrimination, and the need of all sides to save face will require a sensitive and incremental approach to resolving this conflict.

One approach that has been adopted in similarly complex conflicts elsewhere is to find an interim settlement that creates the space for stability and security to take hold and for cooler heads to consider a long-term solution. Arguably, such approaches have a mixed track record. In Croatia, in the second half of the 1990s, a UN-administered interim accord facilitated the eventual reintegration of Serb-majority parts of the country, whereas in Sudan and Kosovo, the creation of new states was the result.

Arguably, the Northern Ireland Agreement and the Papua-New Guinea – Bougainville Agreement also have the option of future constitutional change built in. The Saarland, a territory historically disputed between France and Germany, before and after the Second World War voted for a return to Germany rather than the option of becoming part of France or remaining as an internationally administered territory.

In the current situation, focusing on confidence-building and any such interim solution first and then giving considered thought to a long-term settlement is the only way to avoid the instability and volatility that is a hallmark of so many protracted conflicts.![]()

A version of this article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1f3Xcuu

_________________________________

Tatyana Malyarenko – Donetsk State Management University

Tatyana Malyarenko – Donetsk State Management University

Tatyana Malyarenko is a professor in public administration at Donetsk State University. She previously studied at the National University of Economics and Trade and Donetsk National Technical University. She has published work on competing self-determination movements in Crimea.

Stefan Wolff – University of Birmingham

Stefan Wolff – University of Birmingham

Stefan Wolff is Professor of International Security at the University of Birmingham. A political scientist by background, he specialises in the management of contemporary security challenges, especially in the prevention and settlement of ethnic conflicts and civil wars, and in post-conflict reconstruction, peace-building and state-building in deeply divided and war-torn societies.

1 Comments