Marine Le Pen, of the Front National, and Geert Wilders, of the Netherlands’ Party for Freedom, have announced their intention to form an alliance with several parties across Europe after the European Parliament elections. But how should such an alliance be structured? Zoe Lefkofridi presents an analysis of the coherence of potential members of a new nationalist bloc on three different issues: European integration, immigration, and left/right issues. She finds that the greatest level of coherence is shown between these parties on left/right issues. Framing the alliance around this dimension would therefore make for a more effective force in the Parliament.

Marine Le Pen, of the Front National, and Geert Wilders, of the Netherlands’ Party for Freedom, have announced their intention to form an alliance with several parties across Europe after the European Parliament elections. But how should such an alliance be structured? Zoe Lefkofridi presents an analysis of the coherence of potential members of a new nationalist bloc on three different issues: European integration, immigration, and left/right issues. She finds that the greatest level of coherence is shown between these parties on left/right issues. Framing the alliance around this dimension would therefore make for a more effective force in the Parliament.

We are now at the key event in the political life of the European Union: the pan-European elections to the European Parliament (EP) on 22-25 May. They are anticipated to be the most interesting and critical contests in the history of the Union. Why? What is different this time?

The most obvious answer is the economic crisis and the social deprivation it has caused, especially in Southern Europe. The management of this crisis has seriously challenged the functioning of democracy at both EU and domestic levels. As Brigid Laffan, the Director of the RSCAS, noted in her State of the Union address, during the crisis the EU policy-making system proved resilient, and the euro was ‘saved’; but the Union’s legal framework, governance structures, relations among the member states, and its ability to respond to pressing societal needs have all been challenged since 2009.

There is an effort to personalise EU politics so as to increase interest in EU affairs, and consequently also, turnout at the EP ballot, while the EU’s political mainstream is under pressure to defend integration at times of increasing scepticism. Even worse, the nationalist far-right now attempts to mobilise across borders against further integration. To what extent do these developments matter for citizen representation at the EU level? Can the far-right form a coherent political group in the elected EP?

Europe’s politicisation

The economic and political crisis brought to light the thus far hidden inter-relationship of European and domestic policy. Europe managed to infiltrate national debates; moreover, electoral outcomes in one state were increasingly recognised as affecting the governing coalitions’ vulnerability in other members and the EU as a whole. Thus, EU concerns penetrated deeply (and for the first time) into the conduct and results of recent French Presidential and Greek and Dutch parliamentary elections.

The European question has until now been stuck at ‘in/out’; however, in a globalised world where EU members can hardly act unilaterally, and in a polity as advanced as the Union, the real issue is “which Europe we want”. Compared to all previous crises in the history of European integration, this one attracted unprecedented public attention. Europe’s politicisation is here to stay.

National party organisations across Europe feel quite uneasy with this development because they had long opted for keeping Europe on their organisational and ideological periphery. They treated the single direct transnational election – a key event in the Union’s political life – as unimportant; at best they used it as a barometer of popularity in the national arena. Campaigns focused on domestic issues and the “wrong” EU issues, e.g. constitutional design.

This behaviour, however, not only rendered EP elections tedious affairs, but also discouraged citizens’ engagement with European policies and legislative processes at the supranational level. Up until now, national parties got away with eluding Europe’s politicisation. But the crisis revealed forcefully that EU competences have become too many to ignore and that member states cannot go it alone neither when dealing with financial crisis within the Union, nor when they need to respond to political crises in the Union’s neighbourhood, such as Ukraine.

And while Europe stands at the crossroads, there are those who think in ‘national’ and those who think in ‘European’ terms – at both elite and mass levels. To quote the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs Federica Mogherini, the current crisis revealed the necessity to think as “proper Europeans”. Although on average, European citizens trust their national government much less than they trust the EU, some perceive integration as an opportunity – even a necessary part of the solution, while others see it as the source of all evils.

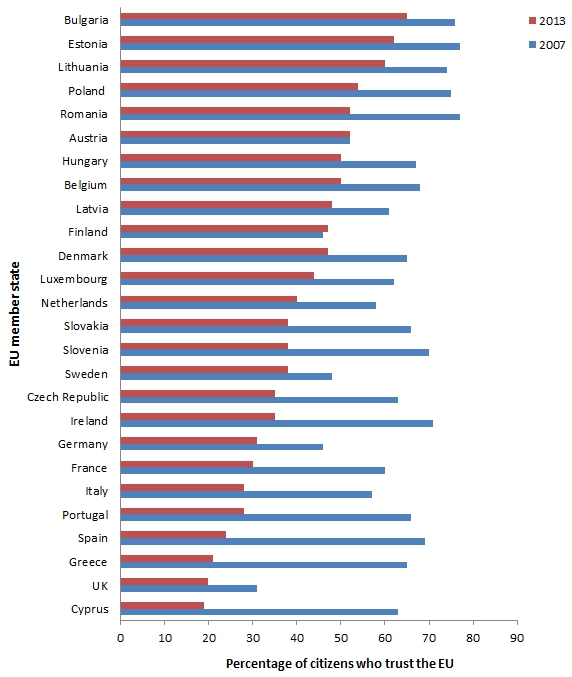

As Chart 1 below shows, with the exception of Finland and Austria, European citizens’ trust in the EU has been significantly shaken. This holds especially in the case of the countries damaged most by the crisis, Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Spain, as well as Eastern European countries. This negative picture comes as no surprise given the EU’s failure to deliver in key areas such as employment, immigration management or a dynamic presence in the global arena.

Chart 1: Percentage of citizens in EU countries who trust the EU (2007 and 2013)

Source: Eurobarometer

Source: Eurobarometer

These somewhat disenchanted European citizens are now called to select the members of a much stronger EP compared to those of the past. Following the latest revision of the Union’s constitutional foundation, the Lisbon Treaty, most areas of EU-level policy are now decided on jointly between the Parliament and national governments in the Council of the European Union. So the composition of the new Parliament will have an important impact on EU legislation.

This election to the EP constitutes a unique instrument for Europeans to express their preferences over a great range of European policies and to be represented in EU policy-making. Precisely for this reason, it is important for European citizens to know where parties stand on various issues and choose those ones with views similar to their own. To make their choices, citizens need information about parties’ stances on key policy issues. For policy representation to work in the EP, which is a multilevel transnational chamber, two conditions must be met.

First, voters should chose “correctly” in that they should select national parties with positions closest to their own on key policy issues. Fortunately, voters across the Union can find this out very easily through euandi – a pan-European online voting advice application that reveals an individual’s congruence on key policy issues with competing parties in all 28 party systems. Knowledge about political offers, both within an individual’s own country and across the EU, is important: thanks to the free movement of people and services, some Europeans live and work in members states other than their country of origin, and can thus choose to vote in any of the two countries.

Second, as no national party can make policy in the EP by acting unilaterally, similarly minded national parties must join forces. Inside the Parliament national parties’ elected deputies form political groups, with which they align when voting on European legislation. National parties need to elect at least 25 MEPs and at least one-quarter of the Member States (i.e. seven countries) must be represented within the group.

In sum, for EP representation to work, two types of “matching” are key: between a voter and their national party, as well as between a national party and national parties from other countries that join together to form a political group. In a recently published piece, we argue and empirically show that when both of these conditions are satisfied, the multilevel channel works quite well, especially on the left-right dimension.

However, Europe’s intense politicisation may challenge existing patterns of policy congruence between the represented and their representatives. The crisis has generated a bitter North-South/creditors-debtors divide, which may affect voting patterns and/or may prove hard to accommodate in the creation of political groups in the EP – both of which are largely determined by ideological congruence on the left-right dimension.

The increasing salience of Europe in times of economic hardship and weak policy performance seems beneficial to the Eurosceptic left and right. Yet, opposition and criticism are healthy elements of any democratic system, which constantly needs to evaluate itself and change towards improvement. One such innovation is the attempt to personalise EU politics, which may also impact on party behaviour (e.g. affiliation strategies; political group formation and cohesion) as well as on voters’ turnout and party choices. But it can also lead to inter-institutional tensions (between the EP and the Council of the European Union).

Personalisation in a multilevel chamber

For the very first time in the Union’s electoral history, candidates for the President of the European Commission have been nominated by European political parties in advance of the elections. The nomination of top candidates constitutes a first attempt to personalise EU-level politics – an experiment to increase turnout, which has traditionally been extremely low by European democratic standards.

However, it remains to be seen how this attempt to establish transnational leadership will play out in the absence of strong supranational parties. Much depends upon national party behaviour and the extent to which they have endorsed and promoted their common candidates in their own country. Due to the North-South divide generated by the crisis it may prove difficult, for instance, to connect Greek and Spanish voters with a German candidate (Martin Schulz) from the Party of European Socialists, or a Luxembourgish candidate (Jean-Claude Juncker) from the European People’s Party. The personalisation experiment will definitely produce important lessons for EU democracy in the years to come.

The candidates have made an effort to connect to a diverse transnational electorate. With the exception of the radical left and right, the candidates from European political parties have held a series of formal debates. While the far right nationalists were absent from these presidential debates because they did not (manage to) field a top candidate, the nominee of the Party of the European Left, Alexis Tsipras, has repeatedly declined participation. In fact, Tsipras was in Italy on May 9 during one of the debates, but not in Florence debating his competitors; he was in Rome to celebrate the Party of the European Left’s 10th anniversary.

Tsipras has therefore both articulated a message in favour of European integration by putting himself forward as a candidate, and at the same time presented a sceptical message towards the institutional and policy status quo, as well as the mainstream parties that managed the crisis and have been in government during recent decades. Most parties located on the extreme left of the spectrum do not reject the idea of European integration per se, but rebuff economic policies pursued at the EU level. In other words, for radicals on the left the question is not “do we want Europe”, but rather about “which Europe we want”.

On the other extreme of the political spectrum, however, we find fanatic supporters of disintegration, and of ‘national sovereignty’; many observers fear the triumph of the far right that capitalises on opposition to European integration and immigration and scores well in domestic polls. Given citizens’ disenchantment with Europe, EU-bashing seems to be a promising electoral strategy. But the question that matters for citizens’ representation remains: even if they thrive electorally, will they be able to form a coherent political group in the transnational EP?

Europe’s far right: united in division?

Contrary to other types of national parties, such as Christian Democrats, Greens or Social Democrats, far right parties have failed to create a political group in the EP. This is partly because they oppose European integration and sitting under the umbrella of a ‘European party’ undermines the core of their ideology, while contradicting their nationalist perception of the world.

Yet, nationalist leaders’ efforts to create a novel political formation after the EP election are part of the strategy to destroy the EU “from within”. The “father” of European Integration studies, Ernst Haas, discussed the possibility of anti-integration parties cooperating across borders to promote short-term/long-term negative expectations vis-à-vis the European project as far back as 1968 but never before has this hypothesis come as close to materialising as it is in 2014.

Lacking a political a group, the “non-attached” far right parties can barely realise any of their policy goals. Under the supranational party umbrella, domestic parties get access to more resources (e.g. office space, funds for support staff or meetings) and more opportunities to influence policy outcomes in their preferred direction. Having realised all this, far-right leaders have been trying to organise across borders.

Aiming at a pan-European alliance of far right parties against the “Monster of Brussels”, Le Pen (FN) and Wilders (PVV) met and discussed with representatives from far-right parties such the Flemish Vlaams Belang (VB) and Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ). Thus far, they have avoided talks with more openly racist-fascist parties such as the Greek Golden Dawn and Hungarian Jobbik, although these parties are viewed as potential coalition partners by the leader of the British National Party (BNP).

Despite having failed to agree on a Commission candidate, hard-core nationalists continue their efforts to form a political group with like-minded parties within the new Parliament – what Wilders has called a “historical project”. This, in turn, begs the question of what such a project would look like. If we were to group these nationalist parties into a political group, would they be able to form a cohesive group that could perform the necessary functions in the EP, such as voting together and pushing legislation in their preferred direction (e.g. disintegration)?

One way to assess such a group’s potential for internal ideological cohesion and congruence with the voters it would claim to represent in the EP is to construct an imaginary political group composed of hard-core nationalist parties. Drawing on prior knowledge of how parties affiliate in the EP, we assume that the currently non-attached nationalist parties would join forces based on congruence on one or more issue dimensions. The question is which issue dimensions would serve as the basis for their alliance.

In the case of this type of party, the prime candidates for this purpose are opposition to immigration and European integration/exit from the EU, as these are their issue priorities in the campaign. It is also useful, however, to know how congruent they are on the general left-right dimension – as this constitutes the main dimension in EP politics. These parties generally want to shift focus away from the left-right dimension and organise contestation by capitalising on the perils of more regional integration and immigration.

Given that the EP party group position is typically very close to the weighted median position among its members, we assume that this would also hold for the hypothetical nationalist group. The closer members are to the ideological position of the median, the more ideologically coherent the group. The proximity of their own supporters to this median also matters for assessing how well the resulting political group could represent them in EP policy-making.

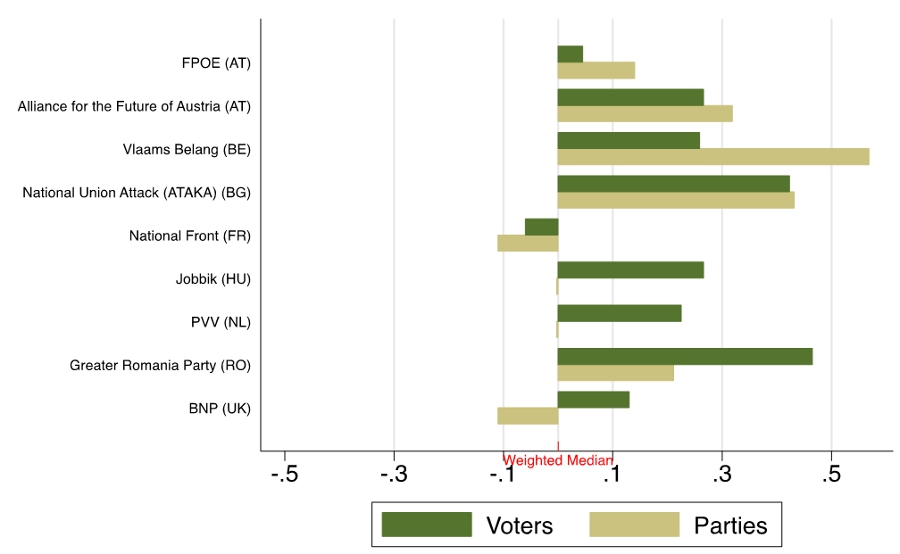

Charts 2-4 below portray the weighted median position (at point 0 in the middle) of non-attached nationalist parties (those for which we had data also on the mass level) on three issue dimensions: pro/anti-EU; pro-anti-immigration, and the general left-right dimension. The dark green bars represent the distance of a party from the median, whereas the light green bars represent the distance of this party’s supporters from the median. The closer parties are to the hypothetical median position, the more ideological coherence.

Chart 2: Distance of non-attached nationalist parties and their voters from the median position amongst these parties on the issue of European integration

Note: The Chart shows how far a party (light green) and its voters (dark green) are from the median position on European integration issues of these parties in a hypothetical European Parliament group. A positive figure shows that parties/voters are more Eurosceptic than the median position of these parties, while a negative figure shows they are less Eurosceptic. Sources: 2009 Voter Survey PIREDEU/EES (van Egmond et al. 2011) and 2009 EU Profiler data (Trechsel 2009).

Chart 2 illustrates that the majority of parties, and especially the Belgian Vlaams Belang and Bulgarian ATAKA (Attack) party, are more Eurosceptic than their weighted median. Moreover, with the exception of the two Austrian parties and the Front National, the distance between parties from their median, and the distance of their supporters from this median differs. Despite agreeing on opposition to Europe, when examining their exact positioning on the issue of integration we observe interesting variation at both party and voter level.

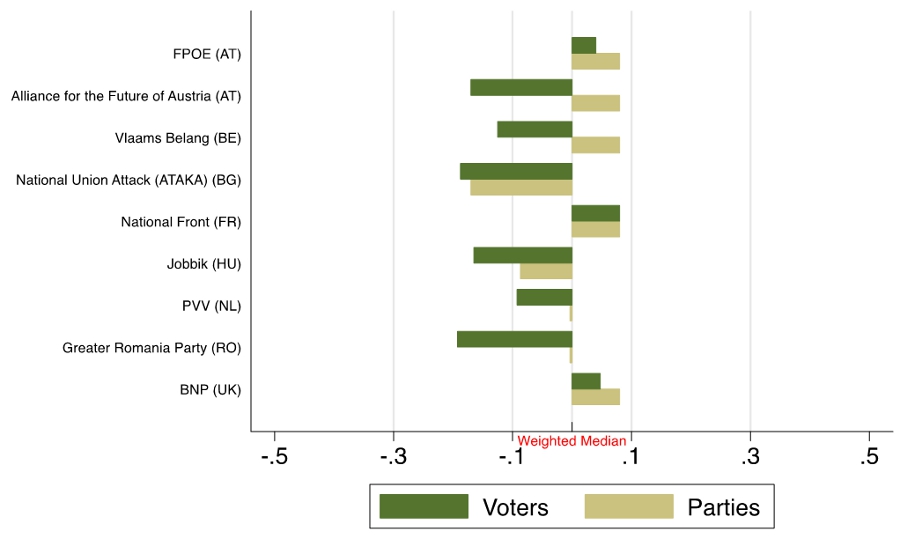

Chart 3: Distance of non-attached nationalist parties and their voters from the median position amongst these parties on the issue of immigration

Note: The Chart shows how far a party (light green) and its voters (dark green) are from the median position on immigration issues of these parties in a hypothetical European Parliament group. A positive figure shows that parties/voters are more strongly against immigration than the median position of these parties, while a negative figure shows they are more in favour of immigration.

Chart 3 shows that on the issue of immigration there is much less divergence compared to the pro/anti-EU dimension. The Bulgarian ‘Attack’ party, Jobbik in Hungary, the Front National; the British BNP; and the Austrian FPÖ seem to be very close to their voters on this dimension, but slightly distant from the median. Distances from the hypothetical median are smaller than on the pro/anti-EU dimension.

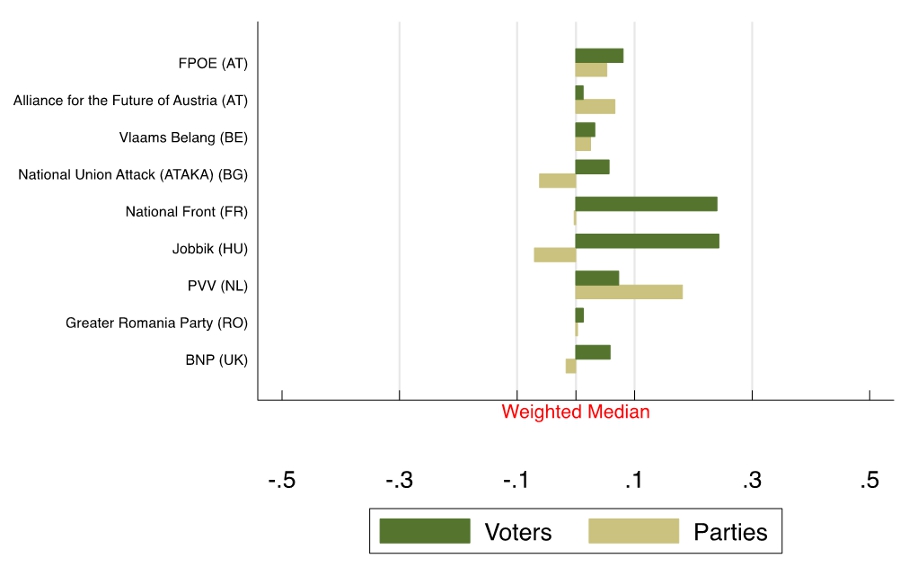

Chart 4: Distance of non-attached nationalist parties and their voters from the median position amongst these parties on left/right issues

Note: The Chart shows how far a party (light green) and its voters (dark green) are from the median position on left/right issues of these parties in a hypothetical European Parliament group. A positive figure shows that parties/voters are more to the right than the median position of these parties, while a negative figure shows they are more to the left, on average.

Finally, Chart 4 shows that the distances between parties and the median are smaller on left/right issues; only the PVV, the supporters of the Front National and Jobbik are located further to the right of the imaginary median.

The examination of the coherence of this hypothetical EU-level party of nationalists on three political dimensions shows that, similarly to other European parties, such as the European People’s Party and Party of European Socialists, the left-right dimension seems to be the obvious foundation for collaboration between the nationalist parties as well. On the left-right they are much closer to each other than on their two most salient issue dimensions (EU and immigration).

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1r0KCDr

_________________________________

Zoe Lefkofridi – European University Institute

Zoe Lefkofridi – European University Institute

Zoe Lefkofridi is Max Weber Fellow at the European University Institute.