The EU has warned Russia that it could face stronger sanctions over the Ukraine crisis. Ruben Zaiotti writes on the role that visas could play in EU sanctions. He notes that applications from Russia make up the largest share of all Schengen visas issued and that Russia has one of the lowest visa refusal rates in Schengen states. He argues that taking a harder line on visa applications from Russia could therefore offer a natural route to exert pressure over Ukraine, however such a policy would also carry a significant cost for EU countries.

The EU has warned Russia that it could face stronger sanctions over the Ukraine crisis. Ruben Zaiotti writes on the role that visas could play in EU sanctions. He notes that applications from Russia make up the largest share of all Schengen visas issued and that Russia has one of the lowest visa refusal rates in Schengen states. He argues that taking a harder line on visa applications from Russia could therefore offer a natural route to exert pressure over Ukraine, however such a policy would also carry a significant cost for EU countries.

It would be a bit of an understatement to say that relations between Russia and European governments have recently turned rather frosty. Indeed, we now typically hear references to a new ‘Cold War’, with Ukraine acting as battleground in this revamped East-West rivalry. Despite the militaristic undertones that characterise their relationship, the growing tensions between the two sides have not led to open conflict. Both, after all, would have a lot to lose from this confrontation. This state of affairs, however, does not mean that another type of war, one not involving tanks and missiles, is being waged. It is a war over mobility of people, fought through an unlikely weapon of mass disruption, namely visas.

European governments have in fact created a ‘black list’ of Russian public officials who are deemed personae non gratae and banned from entering the EU. European officials present this move as an initial warning shot before harsher measures (i.e. economic sanctions) are introduced as a means to put pressure on their Russian counterparts. Whether these threats of escalation will materialise is a matter of debate. It is no secret that Europeans are divided on what to do with Russia, and it is unlikely that they would irreparably antagonise their bilateral relations with Moscow. There is a good chance then that visas will remain Europe’s sole offensive instrument deployed in this conflict. Europe’s mighty arsenal may therefore largely consist of nothing more than a piece of paper.

Still, we should be careful not to underestimate the power of this ‘soft’ weapon. For the Russian elites (be they tycoons or well-connected public officials) access to Europe is a sensitive issue, given their enduring fascination and extensive (and often murky) economic dealings with the Old Continent. Europeans are well aware of this soft spot, and it is therefore not surprising that they are trying to take advantage of it as much they can.

There is another aspect of this conflict that often goes unnoticed, however. The visa issue is not a matter of concern only for Russian elites. The most recent statistics published by Frontex, the EU border agency, are revealing in this regard. As shown in Chart 1 below, by far the largest percentage of short-term uniform visas issued for Schengen countries are for individuals who are based in Russia, at 41.7 per cent of the total in 2012. The country with the next largest percentage of visas issued is Ukraine, at only 9 per cent of the total.

Chart 1: Percentage of short-term uniform visas issued for Schengen countries by country of issue/application (2012)

Source: European Commission Directorate-General Home Affairs

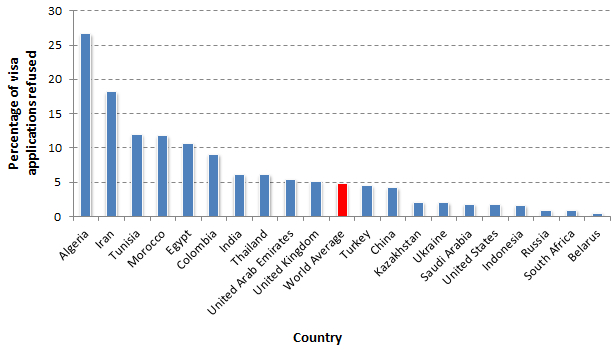

In turn, as Chart 2 shows, the rejection rate for Russian applicants is among the smallest of the top 20 countries where visas are issued. Of those applications for a Schengen visa made in Russia in 2012, only 0.9 per cent were refused. For comparison, the country with the largest refusal rate, Algeria, had 26.7 per cent of applications being refused.

Chart 2: Visa refusal rate for top 20 countries where Schengen visas were issued in 2012

Source: European Commission Directorate-General Home Affairs

This being the case, a cynic might argue that an appealing alternative avenue to intensify the pressure on the Kremlin could well be making it harder for ordinary Russians to obtain the sought-after pass to Europe. And yet banning a rich source of income for a continent still recovering from a devastating crisis does not seem be such a smart move. The potential for such a move to backfire is undoubtedly high.

This route should not be completely dismissed, however. European officials could use the visa issue as a bargaining chip in their dealings with Russia. Indeed, something along these lines is already happening. One example of this is that the EU has refused to allow residents of Crimea to apply for visas via Russian institutions and instead will only provide visas to these citizens if they apply in Ukraine – despite the annexation of the peninsula by Russia. The Commission has justified this by stating that it will issue visas via Ukraine because “Crimea is a part of this country”.

European officials could also include in the mix a possible revival of the longstanding discussion over the lifting of visa requirements for Russian nationals, which even before the latest events in Ukraine had hit some road blocks. The EU suspended negotiations over a visa-free arrangement with Russia in March, after the Crimean crisis began. All things considered, the story of the EU-Russian visa war may just be getting under way.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Feature image credit: Will Bakker (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1kAeVgF

_________________________________

Ruben Zaiotti – Dalhousie University

Ruben Zaiotti – Dalhousie University

Ruben Zaiotti is the Director of the European Union Centre of Excellence and Assistant professor in Political Science at Dalhousie University. He holds a PhD from the University of Toronto, a Master degree from the University of Oxford and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Bologna. He is the author of ‘Cultures of Border Control: Schengen and the Evolution of European frontiers’ (University of Chicago Press, 2011). He also writes on Europe and border control at Schengenalia.

I agree with Ruben that we should not under-estimate the power of visa, namely that of denial or issuance. Neither, however, should we over-estimate it. In this respect, I am referring mainly to the political will of EU leadership. The US visa ban list is far more advanced than that of the EU, where so many members of the Russian elite hold assets – which is my next point: visa denial at inidividual or group level only works when used in concert with other tools, mainly economic. EU visa bans were not followed by mass asset freezes. A Few Russians will be disappointed this year not to make use of their jet ski on the Cote d’Azures, but the acgual status of their wealth, the real reason why they travel to Europe, will be unaffected.

I would like to conclude with a question: is suspending talks on visa free regimes f8r ordinary Russians not counter-productive? If we cannot talk to the Kremlin, why not at least let ordinary Russians soak up Europe. They are hardly in the posoition to put pressure on the government, so why not work on fostering relationships with the leaders of tomorrow through travels, cultural and education exchanges?