The reliance of European states on Russian gas exports has been one of the key underlying factors in the Ukraine crisis. Marco Siddi writes on the role played by the Nord Stream gas pipeline in shaping Germany’s policy toward Russia. He notes that the existence of the pipeline, which runs from Russia to Germany under the Baltic Sea, has freed Germany’s hand to pursue a stronger line over Ukraine. However, the fact that other countries in Central and Eastern Europe are more vulnerable from a suspension of Russian gas exports through Ukraine has ensured that the main costs for a strong German policy would potentially be borne by its eastern allies.

The reliance of European states on Russian gas exports has been one of the key underlying factors in the Ukraine crisis. Marco Siddi writes on the role played by the Nord Stream gas pipeline in shaping Germany’s policy toward Russia. He notes that the existence of the pipeline, which runs from Russia to Germany under the Baltic Sea, has freed Germany’s hand to pursue a stronger line over Ukraine. However, the fact that other countries in Central and Eastern Europe are more vulnerable from a suspension of Russian gas exports through Ukraine has ensured that the main costs for a strong German policy would potentially be borne by its eastern allies.

Eight years ago, shortly after German and Russian leaders agreed on the construction of the Nord Stream gas pipeline, then Polish defence minister Radoslaw Sikorski called it “the Molotov-Ribbentrop pipeline” – a reference to the 1939 pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which partitioned Central and Eastern Europe. According to him, Berlin had sacrificed solidarity with its eastern EU neighbours in order to pursue national interests. Nord Stream, he argued, would allow Russia to keep the flow of gas to Germany unaltered while it simultaneously turned off the tap and blackmailed governments in Central and Eastern Europe. In fact, during the current crisis in Ukraine, the very existence of the pipeline has allowed Germany to take a tougher stance toward Russia than many EU member states in Eastern Europe.

Inaugurated in 2011, Nord Stream provides a direct link (via the Baltic Sea) for Russian gas exports to Germany. Berlin’s reliance on transit countries – notably Belarus and Ukraine – has decreased enormously. According to International Energy Agency data, in 2010 Germany imported 86 per cent of its natural gas demand, which totalled around 90 billion cubic meters (bcm) a year. Russia supplied 39 per cent of German imports. According to the official export statistics of Russian energy giant Gazprom, in 2013 this figure corresponded to around 40 bcm. Also in 2013, Nord Stream transported 23.5 bcm to Germany, but its yearly transport capacity is much higher, at 55 bcm. This means that German gas imports from Russia would be guaranteed even in the case of a complete blockage of imports via Ukraine.

Germany would only face problems at securing imports of Russian gas if tensions escalated further and Russia decided to put an embargo on exports to Berlin via Nord Stream. However, this is highly unlikely. Exports of Russian gas to Germany started in the 1970s and continued uninterrupted during the worst Cold War crises of the early 1980s – those following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the downing of the Korean Airlines flight 007 near Sakhalin and the 1983 nuclear war scare. Furthermore, today revenues from gas sales to Germany (the biggest importer of Russian gas) are an important source for the Russian federal budget. Blocking this flow of energy and cash would seriously undermine vital German and Russian interests, hence it is a step that neither Merkel nor Putin would contemplate under the current circumstances.

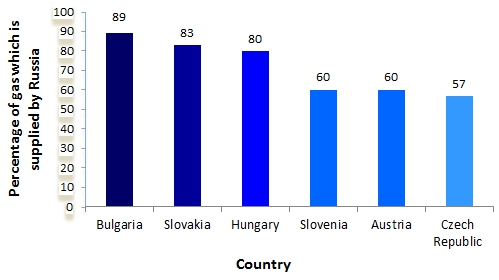

While Russian gas exports to Germany are highly unlikely to face serious disruptions, as the Chart below shows, the same cannot be said of supplies to several Central and Eastern European and Balkan countries. These are the states that rely most on the transit of Russian gas via Ukraine – which, with an estimated capacity of 155 bcm, remains the largest corridor for the westward flow of Russian gas. What is more, these countries are much more dependent on Russian gas supplies than Germany. In Slovakia and Bulgaria, more than 80 per cent of total gas imports come from Russia. The figures for Hungary, Slovenia, Austria and the Czech Republic are between 55 and 80 per cent.

Chart: Percentage of gas supplied by Russia in selected European countries (2012)

Source: The Economist/Eurogas

Other non-EU countries such as Serbia, Macedonia, Moldova and Bosnia are also heavily reliant on Russian gas and on the Ukrainian corridor, while some have limited storage capacity to face potential crises.In January 2009, a Russian-Ukrainian gas price dispute resulted in the interruption of gas supplies to these countries, which paralysed their economies and heating facilities in the middle of the winter.

This helps to explain why the leaders of several Central and East European countries have been critical of EU sanctions against Russia. The prime ministers of Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic have recently stated that sanctions are meaningless and risk hurting the EU more than Russia. Outside the Union, Serbia has refused to align itself with Brussels, despite its EU membership ambitions. On 16 October, Serbian president Tomislav Nikolic hosted Vladimir Putin as guest of honour at a parade celebrating the seventieth anniversary of the country’s liberation from Nazi occupation and told him that Belgrade would not impose sanctions on Russia.

While scepticism toward EU sanctions has increased in Central and Eastern Europe, Germany reiterated its tough negotiating position vis-à-vis Russia at the Europe-Asia summit in Milan, on 16-17 October. Angela Merkel argued that the German and Russian stances on the crisis in Ukraine are very different and implied that her country would continue to back the current, intransigent EU line on Russia, including selected economic sanctions. The German Chancellor may be right about confronting Putin and being suspicious of his true intentions in Ukraine. However, her position appears inconsistent with Germany’s flourishing energy trade with Russia via Nord Stream.

Under these conditions, the main economic risks that Germany is taking by confronting Russia are actually borne by other EU member states – those that would suffer the most if the transit of Russian gas through Ukraine is interrupted. At the end of October, an agreement on Russian gas supplies to Ukraine was reached, with the EU as guarantor for Ukrainian payments. Nonetheless, senior European diplomats such as Václav Bartuška, Czech ambassador for energy security, fear that Russian exports via Ukraine will be disrupted this winter. In order to be consistent, Merkel’s foreign policy towards Moscow would have to put Germany’s own interests at stake, either by using German gas imports via Nord Stream as a bargaining chip with Russia, or by making credible commitments to support exposed EU member states if confrontation leads to the interruption of their gas supplies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image: Nord Stream pipeline, Credit: (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1vm3WwU

_________________________________

Marco Siddi

Marco Siddi

Marco Siddi obtained a PhD in Politics at the University of Edinburgh in September 2014 and is currently research associate at the CRENoS institute in Cagliari. His research focuses on EU-Russia relations.