The European Parliament elections in May saw a number of populist, far-right and Eurosceptic parties gain representation. Alexandre Afonso writes that despite their success, the majority of these parties remain disconnected from other parties at the national and European levels. Presenting a network of European parties, he illustrates that those on the Eurosceptic-right and radical-left are still largely isolated from mainstream politics and the parties of government.

The European Parliament elections in May saw a number of populist, far-right and Eurosceptic parties gain representation. Alexandre Afonso writes that despite their success, the majority of these parties remain disconnected from other parties at the national and European levels. Presenting a network of European parties, he illustrates that those on the Eurosceptic-right and radical-left are still largely isolated from mainstream politics and the parties of government.

A new European Parliament has been sworn in on 1 July, with a greater number of populist Eurosceptic MEPs than ever before. Out of the 751 seats in the European Parliament, 48 are now held by the Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy group, essentially uniting Nigel Farage’s UKIP and Beppe Grillo’s Movimento Cinque Stelle, while 52 are held by non-affiliated parties such as the French Front national, the Dutch PVV or the Austrian FPÖ.

After the success of UKIP or the Front National, many media outlets have mentioned earthquakes, landslides and other geological metaphors to describe changing power relationships that would allegedly change the face of Europe. However, in a political system where alliances and cooperation across political parties at different levels are fundamental, the Eurosceptic populist right remains badly connected and deprived of access to power.

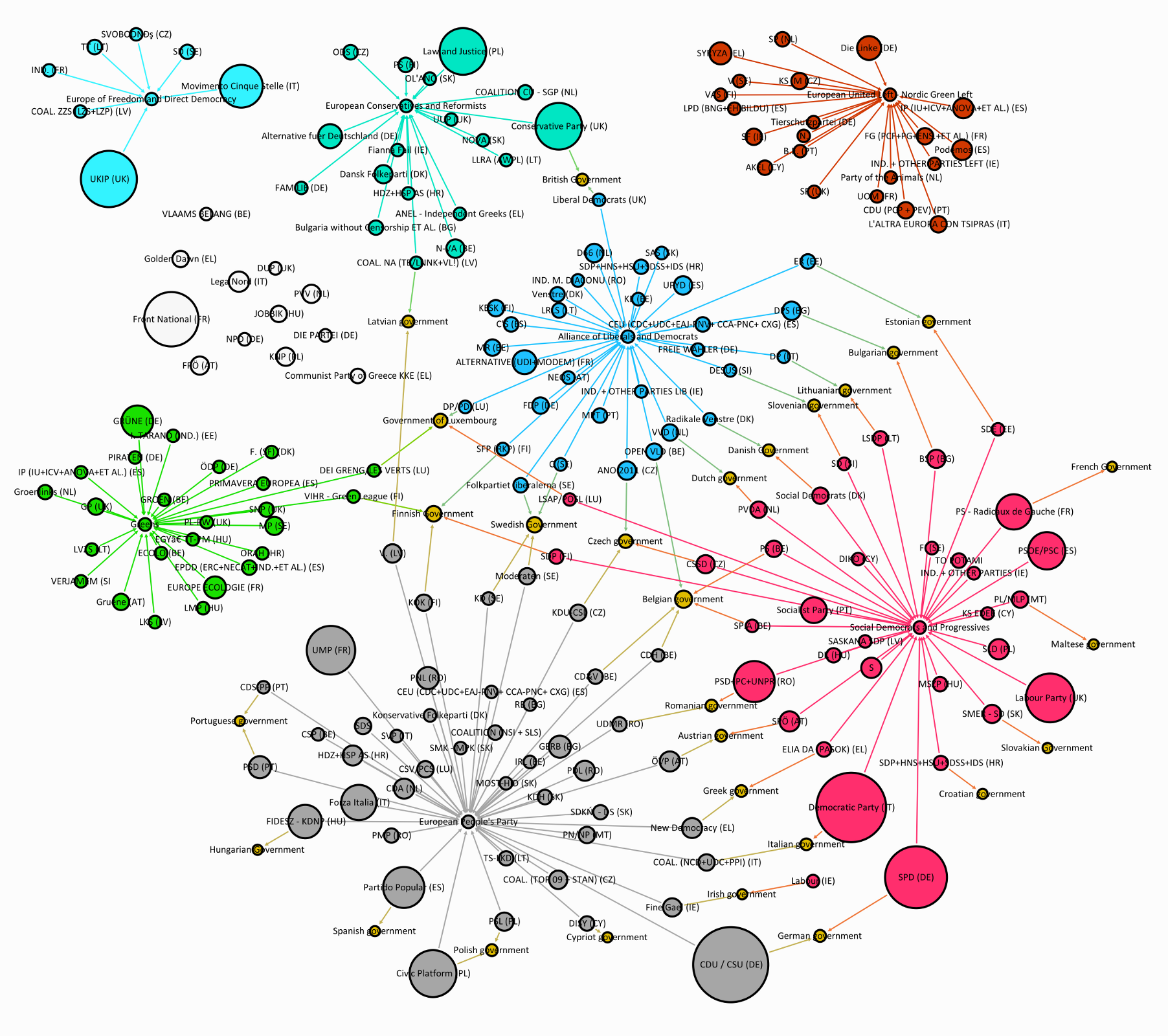

Figure: Network of European political parties (click to enlarge)

Note: For a high-resolution version of this image click here

In the picture above, I have represented the European political system as a network of political parties connected to each other both transnationally and domestically. The nodes in the network represent all political parties that obtained seats in the EP in the last European elections, and their size is proportional to their number of seats. Transnationally, they are connected via their membership in the European political party groups. These groups broadly correspond to the traditional party families: the Social-Democrats (Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats: Labour, German SPD, Italian Democratic party), the centre-right (European People’s Party: the German CDU/CSU, the Spanish PP, the French UMP, Forza Italia), the Liberals (Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe: Liberal Democrats), the Greens, the Radical Left (GUE-NGL: Syriza, Podemos), the Conservatives, and Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (UKIP and Movimento Cinque Stelle).

Many of these parties that co-operate transnationally with like-minded parties are also engaged in government coalitions with other parties at the domestic level. For instance, the German SPD, which is a member of the social-democratic political group, is in a coalition with the CDU, which is a member of the European people’s party. The British Conservatives, who belong to the European Conservatives and Reformists, are in a domestic coalition with the Liberal Democrats, who are a member of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe. Knowing who is connected with whom is interesting because it can play a role in co-ordinating domestic and European policies. In the case of the CDU and SPD, the fact that two of the largest parties in the European Parliament are in a coalition together at the domestic level can provide a strong basis to promote policies.

Unsurprisingly, social-democrats and the European People’s party are well connected via a number of domestic government coalitions. Such “red-grey” coalitions are in place in Romania, Germany, Austria, Greece and Italy. What is perhaps more surprising is the prevalence of liberal/social democratic coalitions, making the Liberals a well-connected party family in spite of their relative electoral weakness. Such coalitions are in place in the Netherlands, Denmark, Slovenia, Lithuania, Estonia and Bulgaria.

In fact, network measures of centrality indicate that Liberals parties are even better connected than the Social Democrats. This is essentially due to the fact that the size of these parties doesn’t allow them to govern alone at the domestic level, and they are therefore forced to coalesce with other parties to be in power, increasing their connectedness. Finally, grand coalitions uniting social-Democrats, Liberals and the centre-right, sometimes with other parties, are in place in Finland, Belgium, and the Czech Republic. Coalitions between centre-right and liberals are rather rare, and only observable in Sweden.

Compared to the days of red-green coalitions in Germany, Green parties appear weakly connected, with members taking part in coalitions only in Luxembourg and Finland. The British Conservatives, by deciding to leave the EPP in 2009, have given up on substantial connections in the sense that their partners in the ECR are mostly small and badly connected, with the exception of their Polish (they are not small) and Latvian (they take part in government) partners.

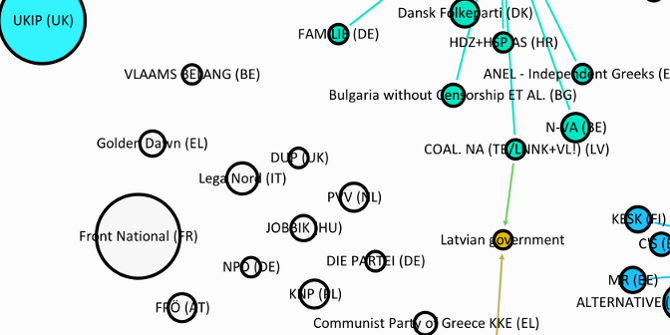

Moving to the Eurosceptic right, in spite of their electoral success, these parties appear clearly isolated, with no link to any coalition government at the moment. This is true both for the parties that failed to form a political group of their own (Marine Le Pen and Geert Wilders did not manage to find partners in a sufficient number of countries), but also for UKIP, whose partners in the “Freedom and Direct Democracy” group are not connected to any relevant party in power. Two exceptions are the Danish People’s Party and the new Alternative für Deutschland, which joined the British Conservatives’ ECR group. The radical left group, which includes Podemos and Alexis Trsipras’ Syriza, also appears isolated, in the upper right corner. Hence, in the absence of the connections and access to power that the mainstream parties possess, the “earthquake” that the media has been talking about is very unlikely to happen.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1xDb1XW

_________________________________

Alexandre Afonso – King’s College London

Alexandre Afonso – King’s College London

Alexandre Afonso is Lecturer in Comparative Politics in the Department of Political Economy at King’s College London. His main areas of research are welfare state reforms, labour market policies, labour migration policies and the role of parties and organized interests in policymaking. Twitter @alexandreafonso

The EU election proved Heads they Win Tails you Lose there is only one Agenda in the EU & that is the creation of a single super state & that ambition overrides any left or right sensibilities. It may take a couple more elections to change the balance to prevent grand coalitions that drive on regardless of the electorates wishes. I wouldnt put it past them to further reduce the voting rights & speaking times of non aligned MEP’s The Eastern MEP’s must feel very at home reminiscing about Brezhnev, Andropov, Chernenko etc

Just one comment – Croatia provides another example of a domestic governing coalition splitting across EP groups, which is not very clear from the networks map. The HNS is part of ALDE, SDP is in the S&D. They ran a joint list in the EP elections, but the elected MEPs joined the party groups that their respective parties are affiliated with. The same thing happened with the center-right opposition: they had a joint list, but split across groups, with one MEP joining ECR, while the others remained in the EPP. This explains why the Croatian coalitions appear in two party groups.