Despite being viewed as a key component of European democracy, media freedom varies significantly across EU states. Based on the annual ‘Freedom of the Press’ report produced by Freedom House, Jennifer Dunham assesses media freedom in EU candidate countries. She notes that seven of the eight candidate or potential candidate states considered have press freedom ratings substantially below the EU average, with Turkey and Macedonia in particular experiencing sharp declines in recent years. She argues that the EU should set explicit press freedom requirements for candidate countries and enforce these more strictly during the accession process.

Despite being viewed as a key component of European democracy, media freedom varies significantly across EU states. Based on the annual ‘Freedom of the Press’ report produced by Freedom House, Jennifer Dunham assesses media freedom in EU candidate countries. She notes that seven of the eight candidate or potential candidate states considered have press freedom ratings substantially below the EU average, with Turkey and Macedonia in particular experiencing sharp declines in recent years. She argues that the EU should set explicit press freedom requirements for candidate countries and enforce these more strictly during the accession process.

The European Union has consistently been among the best-performing regions in Freedom House’s annual Freedom of the Press report, which assesses the condition of media freedom around the world. However, the EU’s average score in the report has dropped over the past five years, a result of sharp declines in Hungary and Greece and more modest deterioration in the United Kingdom and Spain.

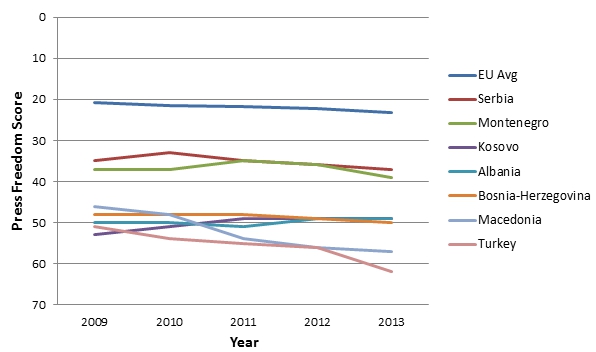

The EU’s score for the report covering 2013 was also pulled down by the inclusion of Croatia, the bloc’s newest member. Croatia’s score (40) was far below the EU average (23.29) on Freedom of the Press’s 100-point scale, with 0 representing the best possible conditions and 100 the worst. Similarly, as shown in the Chart below, seven of the eight EU candidate or potential candidate countries – Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Turkey – score significantly below the EU average (Iceland, with a score of 12, is the exception).

Chart: Press Freedom Score in aspiring EU member states (2009-13)

Note: The Press Freedom Score assigns a value between 0 and 100 (0 being the best possible conditions for a free press, 100 the worst). The vertical axis is presented in reverse order to show the countries with the most press freedom at the top of the Chart. For a full explanation of the methodology see the Freedom of the Press report from Freedom House.

Nations are required to meet certain criteria before they are even invited to begin the accession process. Respect for freedom of expression and the media is deemed to be a “key indicator” of a candidate’s readiness to join the EU; however, there appears to be little in the way of hard hurdles regarding media freedom in the accession process. Chapter 10 of the 35 negotiating chapters addresses “information society and media,” but it focuses on eliminating barriers in the telecommunications market and establishing strong, uniform regulatory frameworks. Media freedom has also been addressed as a small part of Chapter 23, “judiciary and fundamental rights”.

If the EU is to maintain its stellar performance on freedom of expression, it should insist that candidate countries specifically demonstrate adherence to basic standards regarding press freedom laws and practices, while keeping its own house in order so as not to set a bad example for prospective members.

The countries of the Western Balkans feature common areas of concern in their media environments: defamation laws that impose either criminal penalties or high fines; the willingness of politicians and businesspeople to use these laws in an effort to silence critical reporting; weak freedom of information laws; a lack of independence at regulatory bodies; pro-government bias at the public broadcaster; editorial pressure from political leaders and owners at private outlets, leading to censorship and self-censorship; harassment, threats, and occasional attacks on journalists; opaque ownership structures; and manipulation of content via economic pressures.

These characteristics do not exist in a vacuum, but are linked with problems – including corruption, lack of judicial independence, and weak rule of law – that are acknowledged as key factors delaying EU accession. A free, independent press capable of exposing these problems and challenging national and local leaders to address them in the open is essential for any state wishing to enter the EU.

Figure: Map of Press Freedom in Europe (click to enlarge)

Note: For a full explanation of the methodology and the scores see the Freedom of the Press report from Freedom House.

Montenegro

Montenegro, which has made the most progress of any current candidate toward EU accession, has exhibited disturbing press freedom violations in recent years, causing its press freedom score to drop significantly. This is primarily a result of increased hostility toward independent media since Prime Minister Milo Đukanović returned to office in 2012, including negative rhetoric by officials, serious violence against the press, and the manipulation of advertising to punish critical outlets. While numerous press freedom monitors, including Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) media freedom representative Dunja Mijatović, have vocally criticised the worsening situation in Montenegro, the EU has taken a more muted tone, noting, at the March 2014 opening of Chapter 10, “the importance [the EU] attaches to the protection of media freedom and media pluralism.”

Macedonia

The press freedom environment in Macedonia, whose candidate status is stalled due to a long-standing name dispute with Greece, has deteriorated at an even more alarming pace. The score has declined 11 points since 2010 due to growing threats and harassment aimed at critical news outlets by the government of Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski and its media allies. The abrupt 2011 closure of four outlets controlled by Velija Ramkovski, a leading opposition-oriented media owner (he was imprisoned for 13 years in 2012 on charges of tax evasion and money laundering), drastically altered the media landscape.

In 2013, the situation declined even further due to the case of investigative journalist Tomislav Kezarovski, who was kept in pretrial detention for several months and then sentenced to four and a half years in prison on charges of revealing the identity of a protected witness. The government also passed a packet of media legislation in late 2013 that could curb freedom of speech; the laws were amended in January, though they were still criticised by the country’s journalists’ union. Macedonian free press advocates decry the EU’s weak reaction to the ongoing violations in their country, which have been well documented by local and international monitoring groups.

Albania, Bosnia, Kosovo and Serbia

Meanwhile, the other Balkan candidates have shown little progress – or backsliding – over the past five years. The scores for Albania, Bosnia, and Kosovo all hover near the midpoint of the Freedom of the Press scale, while Serbia performs slightly better, at 37. There is evidence that the carrot of EU membership has led some of these countries to attempt at least cosmetic reforms of their media laws to align them with international best practices, but real change is still lacking.

In 2012, Albania enacted reforms to its defamation laws. While the abolition of jail terms was a step in the right direction, defamation remains a criminal offence. As the EU’s latest progress report for Albania found, “Further efforts are required to ensure proper implementation of amendments on defamation and guidelines on setting damages at a reasonable level, in particular through training of the judiciary.” It is also worth noting that these reforms were the product of years of lobbying by, and consultations with, local and international civil society groups.

Similarly, in 2013 Bosnia proposed amendments to its weak freedom of information law that sponsors claimed would bring the legislation into compliance with EU standards. However, the changes, ostensibly intended to protect privacy, received international criticism for severely restricting access to information. Article 8.2 of the draft law, in particular, drew widespread condemnation for its proposal to move large quantities of information out of the public domain, including information on how public funds are spent on social welfare and court decisions in cases not considered to be “of public interest.” Mijatović and media advocacy groups called for the reforms to be rolled back.

Despite 2012 changes in the laws governing Kosovo’s Independent Media Commission and the public broadcaster, Radio Television of Kosovo, the EU still criticises the entities as politicised and lacking independence. Meanwhile, media advocates in Kosovo have little faith that statements from the EU will bring about any meaningful improvements to the widespread problems in the media environment. In Serbia, although the legal framework for the protection of media freedom is broadly in line with EU standards, the media environment remains constrained by political pressures, pervasive corruption, a climate of impunity, regulatory setbacks, and economic difficulties. Implementation of a long-awaited media strategy, proposed in 2011, has proceeded slowly.

Turkey

In Turkey, the decline in the media environment can be viewed in the context of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s drive to consolidate power. In 2013, anti-government protests and leaks indicating high-level corruption resulted in violence against journalists, restrictions on the internet, and firings at several major outlets, causing Turkey’s press freedom score to decline sharply, and its status to fall from ‘Partly Free’ to ‘Not Free’. Constitutional guarantees of freedom of the press and expression are only partially upheld in practice, undermined by restrictive provisions in the criminal code and the Anti-Terrorism Act. The wave of firings highlighted the close relationship between the government and many media owners, and the formal and informal pressure that this places on journalists. Nevertheless, Turkey is an important diplomatic and economic partner for the EU, and the bloc appears willing to overlook Turkey’s shortcomings in the area of press freedom – as well as basic democratic rights and freedoms – to preserve this partnership.

Media freedom requirements for candidate countries

In 2011 and 2013, the EU hosted so-called Speak Up conferences on media freedom in the Western Balkans and Turkey, bringing together international experts, government officials, journalists, and civil society from the candidate countries to discuss the main challenges to press freedom. However, conditions in the countries in question have either stagnated or deteriorated since these conferences were held. Moreover, all of the most recent progress reports describe serious, systemic problems in the candidate countries’ media environments. In February, the EU released further guidelines for “support to media freedom and media integrity in enlargement countries.” These guidelines lay out admirable standards and benchmarks for the candidate countries, but there is no indication that failure to meet them will be an obstacle to EU entry.

The EU cannot accept cosmetic fixes when it comes to media freedom. Instead, it must explicitly require candidate countries to adopt international best practices – in terms of the legal, regulatory, and economic environments for the media – in order to win membership, and enforce these standards when press freedom comes under pressure from within.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Feature image credit: Vratislav Darmek (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1q4EhVP

_________________________________

Jennifer Dunham – Freedom House

Jennifer Dunham – Freedom House

Jennifer Dunham is a project manager for the annual Freedom of the Press and Freedom in the World reports at Freedom House, a U.S.-based independent watchdog organisation dedicated to the expansion of freedom around the world.

Im my humble opion probably could be good idea set it for state members as wel.

Certainly Hungary and Italy would add weight to this idea. I suppose the problem is that while the EU can exert influence on candidate countries (it has something they want – EU membership) once they join the chance of the EU generating real change in member states is smaller.