Bulgaria is holding parliamentary elections today, after the government led by Plamen Oresharski resigned in July. Kyril Drezov gives a final overview of the campaign and the main parties competing in the election. He argues that while much will depend on which of the small parties overcome the four per cent electoral threshold, there is every likelihood of another hung parliament emerging from the vote, as happened in the last Bulgarian election in 2013.

Bulgaria is holding parliamentary elections today, after the government led by Plamen Oresharski resigned in July. Kyril Drezov gives a final overview of the campaign and the main parties competing in the election. He argues that while much will depend on which of the small parties overcome the four per cent electoral threshold, there is every likelihood of another hung parliament emerging from the vote, as happened in the last Bulgarian election in 2013.

Bulgaria is facing another early election less than year and a half after a previous early election in May 2013. After a long summer recess the election campaign picked up around mid-September, but remained fairly dull and uninspiring until the end, with the leading parties trading accusations of financial versus social irresponsibility before a sceptical electorate.

Many of the reasons for early elections this year are similar to the reasons that brought about early elections in 2013, notably unpopular governments and mass protests in both cases. Another similarity is that public interest in the coming election has not increased compared to last year’s: latest opinion polls predict around 50 per cent electoral activity, which is essentially the same as in last year’s parliamentary elections (51 per cent).

However, there are also pronounced differences. In 2013 the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) benefited from widespread expectations – even among non-BSP voters – that its return to power would correct the worst abuses of the then ruling Citizens for Bulgaria’s European Development (GERB). Now, after the dismal experience of the BSP-propped government of Plamen Oresharski, which set new lows in terms of subservience to oligarchic interests, there is widespread resignation amongst the public that the two major parties differ very little as far as abuse of power goes.

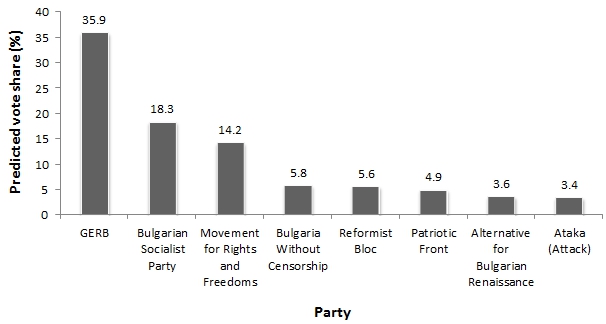

This explains why the dismal failure of a BSP-supported government has not led to a groundswell of support for GERB. Opinion polls in September give GERB on average around 35 per cent of the vote, which is halfway between their worst result in parliamentary elections last year (30.5 per cent) and respectively their best result in 2009 (39.7 per cent). Similarly, opinion polls for the same month give BSP around 20 per cent of the vote, which demonstrates a decline compared to their share of the vote in 2013 (26.6 per cent), but is still better than a notably worse performance in the 2009 parliamentary elections (17.7 per cent). In other words, even after Oresharski’s debacle the electorate has not warmed to GERB too much, and neither would it look to punish BSP too harshly. The September polls give both parties a modest increase compared with their results in the European Parliament Elections in May this year, when GERB gained 30.4 per cent of the vote and BSP obtained 18.94 per cent.

Chart: Vote shares in a recent Gallup opinion poll ahead of the 2014 Bulgarian parliamentary elections

Note: Figures are from a Gallup opinion poll on 22 September which asked the question: “If the elections for the National Assembly were happening now, which party would you vote for?” The Bulgarian Socialist Party runs as part of an electoral alliance, the Coalition for Bulgaria, which includes several parties: the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), Party of Bulgarian Social Democrats, Agrarian Union “Aleksandar Stamboliyski”, and Movement for Social Humanism. For more information on the other parties see: Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB); Bulgaria Without Censorship; Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS); Alternative for Bulgarian Renaissance (ABV); Reformist Bloc; Ataka (Attack); Patriotic Front. Chart is provided for illustrative purposes and is not an attempt by the author to predict the outcome.

For all the public scepticism towards GERB and BSP as tried and tired establishment parties, these two parties are certain to set the tone of government and opposition after the 5 October elections. However, the latest opinion polls outline the possibility of a parliament with five to eight parties (there were only four after the 2013 elections – GERB, BSP, Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS) and Ataka (Attack). This would make the task of forming a government even more difficult, and may lead to minority government and new elections.

GERB’s triumphalism

Throughout September most opinion polls gave (GERB) a solid lead of 10 to 15 per cent over runner-up Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP). In the media, party leader Boyko Borisov repeatedly blamed the previous BSP-dominated administration for bringing the country close to financial catastrophe, and appealed to the voters to give GERB a solid majority as the only way to save Bulgaria from disaster. Thus GERB clearly staked its campaign on being better on the economy, compared with the BSP’s electoral focus on social justice (which built upon increases of social spending under Oresharski).

Borisov also made a far grander show of being supported by the European People’s Party, compared with the BSP’s relative desertion by their colleagues from the Party of European Socialists. GERB’s campaign ended on 3 October with a prominent display of a letter of support from German chancellor Angela Merkel.

For all the bravado about past achievements and European support, Borisov and GERB remained largely silent about the one issue that mostly tarnished their image in the previous early elections: the heavy-handed patronage politics of GERB’s last administration. Many voters, especially outside the capital, dread the GERB clientele’s likely return to influence after the October elections.

BSP’s modest recovery

Opinion polls gave BSP far worse figures over the summer (variations around 13-15 per cent), and there was speculation that it may trail behind its previous government partner Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS) in the October elections. BSP was paying a price for supporting the unpopular Oresharski government to the last, and also for a prolonged refusal of party leader Sergey Stanishev to resign after the double blow of electoral failure (in the European elections) and government failure.

On 27July a BSP congress elected National Assembly Chairman Mihail Mikov as its new leader, replacing Stanishev, who chose to remain an MEP and continued as leader of the Party of European Socialists. Mikov was the preferred choice of the party apparatus and outgoing leader Stanishev, but he was also genuinely popular with rank and file BSP members. Unlike Stanishev, who always felt more comfortable on the European level, Mikov projects the impression of feeling genuinely at home with the traditional BSP electorate.

In the run up to the October elections Mikov attempted a return to the BSP’s roots by focusing its election campaign on the need to enhance ‘social justice’, outlining as a priority the reintroduction of progressive taxation (since 2008 Bulgaria has had a 10 per cent flat income tax, ironically introduced when former BSP leader Sergey Stanishev was Prime Minister and Plamen Oresharski was finance minister). Thus under Mikov, the BSP’s influence experienced a modest recovery, as demonstrated by opinion polls, but not enough to catch up with GERB.

Other parties

Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS): Opinion polls give MRF a fairly constant share of around 15 per cent of the vote, which is a reflection of its stable Turkish and Muslim electorate and is close to the 14 per cent it got in 2013. After the collapse of Oresharski’s government in the summer, the DPS unceremoniously ditched the BSP (its traditional coalition partner) and initiated rapprochement with GERB that led to joint tactical voting in parliament by both parties.

In the same period the party also managed to improve relations with Turkey’s ruling party and President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, which have been adversarial at least since 2009. On 12 September the party’s leader Lyutfi Mestan and other DPS activists met with President Erdoğan in Ankara, which sent an important signal both to the party’s traditional electorate and to other political actors in Bulgaria. After the elections DPS is likely to be in opposition, but would work hard to retain some influence over government decisions by using ethnic and religious scaremongering if needed. Tellingly, their leader Lyutfi Mestan concluded his party election campaign with the warning that ‘without DPS it would be impossible to form a stable majority’.

The Reformist Bloc (RB): The Reformist Bloc was formed as a coalition in mid-2013 by seven small right-wing and centrist parties. September opinion polls give it 6-7 per cent, which is essentially the same as it gained in the European elections last May (6.45 per cent). The RB was seemingly in existential crisis and near disintegration in the summer, but has recovered remarkably well with the election campaign. However, it remains organisationally weak and fractious, and its relations with Borisov and GERB have dramatically worsened during the campaign. Thus, despite their ideological similarity, a coalition between GERB and RB does not look likely at this moment.

Bulgaria Without Censorship: This unashamedly populist party was created in early 2014 by popular TV anchor Nikolay Barekov. It gained just under 10.7 per cent in the European elections and September opinion polls give it 5-7 per cent. In the summer, the party was rocked by scandals and defections, but has recovered well by September, not least by outspending all other parties in its media campaign (keeping alive suspicions that it is a lavishly funded oligarchic project to tap popular discontent). Barekov would be ready to support any coalition, for a price.

Patriotic Front (PF): This is a nationalist project of Valery Simeonov, owner of cable television SKAT. He had previously launched Ataka, as a television project at first, and then as political party in 2005, only to fall out with Ataka’s leader Volen Siderov in 2009. September opinion polls give PF 4-5 per cent, so it is on the verge of entering parliament. If it does, the PF could be one of GERB’s more likely coalition partners.

Ataka: The party was near extinction after the European elections, where it gained less than 3 per cent of the vote (compared to 9.4 per cent in 2013). However, it has recovered surprisingly well by early October, with opinion polls giving it just above 4 per cent. If it enters parliament again, Ataka would focus on publicity stunts and is likely to be shunned by GERB, especially if the latter strikes an agreement with the more polished PF.

ABC (Alternative for Bulgarian Renaissance, abbreviation in Bulgarian ABV – the latter stand for the first three letters in the Cyrillic alphabet): This is an off-shoot of the BSP, formed round former president Georgi Parvanov. It is yet another party that hovers just above 4 per cent in recent opinion polls. If it enters parliament, it may also be a potential coalition partner or GERB.

Conclusion

The October elections may lead to widely different political combinations, depending on how many parties enter parliament. At the moment only five parties – GERB, BSP, MRF, The Reformist Bloc and Bulgaria Without Censorship – look certain to enter parliament; three more parties (The Patriotic Front, Ataka and ABC) are hovering close to the 4 per cent threshold, and thus hard to predict. The big question after the election is whether GERB would manage to form a stable coalition and ruling majority.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image: Boyko Borisov, Credit: European People’s Party (CC-BY-SA-ND-NC-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1vE4pqu

_________________________________

Kyril Drezov – University of Keele

Kyril Drezov – University of Keele

Kyril Drezov is Lecturer in Politics and core researcher of the Southeast Europe Unit (SEU) at the University of Keele. He is an expert on Bulgarian, Macedonian and Balkan politics.