How powerful are business interests in lobbying for changes to EU legislative proposals? Andreas Dür, Patrick Bernhagen and David Marshall present findings from an analysis of 70 legislative proposals introduced by the European Commission between 2008 and 2010. They note that contrary to popular opinion, business actors proved far less successful than citizen groups at achieving their desired outcomes in EU legislative decisions. They reason that this may be because with the single market completed in most areas, the contemporary European legislative agenda tends to be dominated by proposals aimed at protecting consumers or the environment.

How powerful are business interests in lobbying for changes to EU legislative proposals? Andreas Dür, Patrick Bernhagen and David Marshall present findings from an analysis of 70 legislative proposals introduced by the European Commission between 2008 and 2010. They note that contrary to popular opinion, business actors proved far less successful than citizen groups at achieving their desired outcomes in EU legislative decisions. They reason that this may be because with the single market completed in most areas, the contemporary European legislative agenda tends to be dominated by proposals aimed at protecting consumers or the environment.

From legislation governing the safety of chemicals (REACH) to the EU’s current data protection regulation, critics of business lobbying warn that corporate interests are highly influential in EU legislative politics. But do business interests really pull the strings in Brussels? In the framework of INTEREURO, a collaborative international study of lobbying in the EU, we took up the question of business power in EU legislative politics. Our findings have just been published in a recent article in Comparative Political Studies – also available as an ungated working paper.

Our result, at first, seems surprising: Business interests are less successful, on average, in achieving favourable policy outcomes in the EU than citizen groups that advocate issues such as environmental protection or human rights. This result rests on highly labour-intensive empirical research. We interviewed officials in the European Commission about a sample of 70 legislative proposals introduced by that institution between 2008 and 2010. These interviews provided us with data about the conflictive issues within the proposals and the positions of interest groups that lobbied on these issues. We also recorded the positions of the Commission, the Council and the European Parliament, as well as the locations of the status quo and the outcome of the decision-making process. In total, we found 112 conflictive issues and 1,043 non-state advocates lobbying on these issues.

We used these data to calculate a measure of lobbying success, built on the idea that lobbyists are more successful the more they manage to pull the outcome closer to their ideal points, relative to the status quo. The larger the distance to the status quo, and the smaller the distance to the outcome, the more successful an actor should be considered (and vice versa).

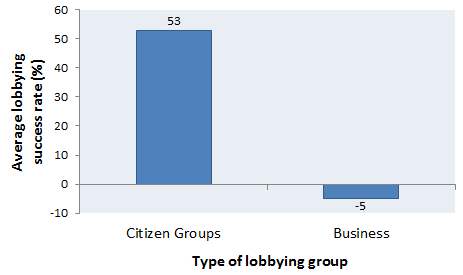

We then analysed variation across actors with respect to this success score. Controlling for a variety of factors such as media attention, the actors’ endowment with relevant information, the distance between the actors’ ideal positions and the European Commission’s position (and in some variations also distance to the Council majority and distance to the majority in the European Parliament), and the number of actors pulling in the same direction, we found that business actors are, on average, less successful than citizen groups. An illustration of our results is shown in the chart below.

Chart: Average lobbying ‘success’ for citizen groups and business actors in the EU’s legislative process

Note: The chart is based on subtracting the percentage of citizen groups/business actors that ‘lost’ in their attempts to influence a given legislative proposal from the percentage of groups that ‘won’ (based on the authors’ ordinal success ‘score’). In this case, 65% of citizen groups ‘won’ and 12% ‘lost’, while only 39% of business actors ‘won’ whereas 44% ‘lost’. For full calculations see the authors’ longer paper.

While at first sight this finding may be surprising, the fact that business influence on EU legislation is limited actually makes sense. Contrary to citizen groups, business interests often lack a “natural ally” in contemporary EU legislative decision-making. With the single market largely completed, much of the EU’s contemporary legislative activity is about regulating the European market. In the mature European polity, proposals aiming to protect consumers or the environment tend to dominate the legislative agenda.

On these proposals, business actors – often unanimously – defend the low regulation status quo. By contrast, citizen groups, the European Commission and the European Parliament all tend to support these proposals. Beyond substantive grounds, the European Commission has an incentive to advance these proposals as doing so gives it the opportunity to strengthen or at least preserve its position vis-à-vis the other EU institutions.

With business actors thus confronting coalitions of citizen groups, the European Commission and the European Parliament, it is not surprising that they often tend to lose. In fact, what we see is that nearly all of the proposals on the EU’s legislative agenda get approved eventually. On most of these, we see a shift away from a low-regulation status quo favoured by business interests towards a high-regulation state favoured by citizen groups.

This is exactly what we are witnessing in the case of the EU’s aforementioned data protection regulation. Although not yet finally approved, it seems likely that the regulation will go through in 2015 despite strong business opposition from large companies including Google, Facebook and Microsoft. The result, while probably less far-reaching than the original Commission proposal, is unlikely to be a success for business. Business lobbying in the EU in this and many other cases is of a defensive nature; we see so much of it because business actors face a loss that they try to minimise.

What conclusion can we take away from this research? Overall, the project of European integration has been a major success for European business. Business actors on average benefitted from the liberalisation of intra-European trade. In the current phase of European integration, however, the popular perception of powerful business lobby groups likely overestimates the actual level of influence business exerts on EU legislation. On the whole, business actors now appear to be less successful than citizen groups in achieving their desired policy outcomes.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: (CC-BY-SA-ND-NC-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1A4o8nW

_________________________________

Andreas Dür – University of Salzburg

Andreas Dür – University of Salzburg

Andreas Dür is Professor of International Politics at the University of Salzburg, Austria. He has published a book, several edited volumes and close to 40 peer-reviewed articles on interest group politics, trade policy and European integration.

Patrick Bernhagen – University of Stuttgart

Patrick Bernhagen – University of Stuttgart

Patrick Bernhagen is Professor of Political Science at the University of Stuttgart, Germany. He is the author of The Political Power of Business (Routledge) and of over 20 peer-reviewed journal articles on citizen participation, lobbying and corporate political activity.

David Marshall – University of Aberdeen

David Marshall – University of Aberdeen

David Marshall is a Research Fellow in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Aberdeen. He has published a number of articles on interest group politics in the European Union.

Hi,

It might be I am not fully undestand the methodology, but how do you know that alleged “citizen groups” are not funded by business to represent its interests?

Hi Victor, this is an interesting question. We certainly carried out a detailed analysis on each stakeholder that was identified as important to the decision making process. As a consequence we re-coded a small number of groups that, although superficially appearing to be citizen groups, turned out to have a membership made up wholly or significantly from large businesses. All of the groups we uncovered were within the extractive industries. Interestingly, for two such groups the policy makers themselves were unaware of the groups make-up, so your point is very well taken.

David

Fascinating research project. It much covers the same area than mine: Can you identify differences in industry incumbents and new entrants? – Or cluster business lobbying activities according to industries? (innovation, tec, digital …)

Apart from that, I do feel that such regulatory discourse groups (lobby groups) are not per se negatively impacting policy outcomes for society as a whole: Not necessarily do interests between a “citizen” and a “consumer” diverge. Thus one should look even closet at the positive side of lobbying.

I’ll try to reach out to you via email. I’m a researcher at WU Vienna Department Strategy & Innovation/Energy Strategy Think Tank. And a doctoral student in CH.

Just a thought, based on my own experience of working on the lobbying side:

Businesses are usually using lobbying to block the passage of legislation, to add ‘pork barrel’ amendments, or to influence the overall strategic direction in a particular area. Their interests are often very narrow and technical, and the lobbying process is treated like a negotiation (i.e. you ask for more than you expect).

Citizens’ groups usually amass around a particular issue which requires new legislation. TTIP is perhaps the main exception. A citizens’ group is naturally more likely to be broad base, diverse, tending to reflect a consensus position. Citizens are unlikely to lobby the EU on a large scale unless the issue is something really major, that has media “cut through”.

As a business lobbyist, you are naturally focused on goals where you know your moral case is weak (tobacco, alcohol, sugary drinks, etc.). You may even know that you have no chance in the long term of achieving your stated goal, so you simply try to slow down the passage of legislation by extending the debate. You may be satisfied with some fairly minor concessions, because at the level of a large multinational, these minor concessions could translate into millions of euros of revenue.

Moreover, as a business lobbyist, it is really not in your interest to trumpet any successes. You always want the regulators to feel they have won, even if you secretly know that you have done well out of the deal.

So it’s two totally different games being played, and naturally the score count on the business side looks worse.

Having said all that, I agree that the EU handles business lobbies better than most national parliaments, and the regulatory process is actually pretty fair. Having 28 member states does make it hard for anyone to buy influence at the European level, and the cushty jobs in Brussels actually incentivise bureaucrats to not risk their nice life over a corruption scandal. It’s not a bad system at all.