The Greek government is still attempting to negotiate a long-term solution to the country’s debt problem, but what are the lasting implications of the 2015 Greek parliamentary elections for politics in Greece? Alexia Katsanidou and Simon Otjes present a new model for understanding the Greek party system. They argue that with the country’s economy becoming so closely linked to the issue of Europe, politics within Greece can no longer be understood along traditional left-right lines. Instead parties are now distinguished on the one hand by their stance toward the country’s bailout programme, and on the other by a cultural dimension which incorporates their stances on immigration and other socio-cultural issues.

The Greek government is still attempting to negotiate a long-term solution to the country’s debt problem, but what are the lasting implications of the 2015 Greek parliamentary elections for politics in Greece? Alexia Katsanidou and Simon Otjes present a new model for understanding the Greek party system. They argue that with the country’s economy becoming so closely linked to the issue of Europe, politics within Greece can no longer be understood along traditional left-right lines. Instead parties are now distinguished on the one hand by their stance toward the country’s bailout programme, and on the other by a cultural dimension which incorporates their stances on immigration and other socio-cultural issues.

Most of the coverage following the Greek elections on 25 January has focused on the new government’s attempts to negotiate a deal over the country’s debt – with a provisional four month extension of the existing bailout programme being announced on 20 February. The elections were also significant, however, due to the profound changes which have taken place in the Greek party system since the previous parliamentary elections in 2012.

The result of the elections initially puzzled many observers given the nature of the new governing coalition. The government that emerged consisted of Alexis Tsipras’ Coalition of the Radical Left (Syriza) and the Independent Greeks (ANEL), a nationalist, populist party. This raised the question as to why a party of the radical left would choose to cooperate with a radical right-wing populist party. The key to understanding why this occurred is to appreciate the changing nature of the Greek political space.

In the literature on European party systems, one model currently dominates. It has been put forward most eloquently by Hanspeter Kriesi and co-authors in a 2008 book which identifies two separate dimensions within a party system. First, there is an economic dimension that separates the left from the right. This dimension concerns issues such as privatisation, budget cuts and welfare state reforms. Second, there is a cultural dimension that separates parties favouring national demarcation (closed borders, less EU integration) from parties favouring European integration and open borders.

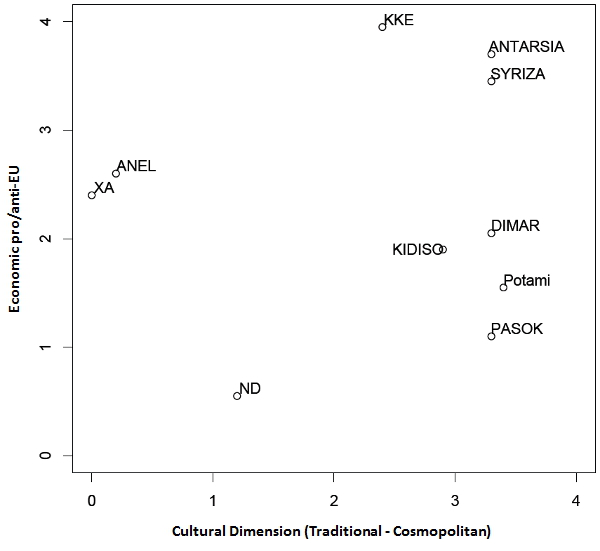

However, this model clearly fails to describe the Greek policy space. Instead, we have developed an alternative two-dimensional model of the Greek party system, with a dimension that concerns cultural issues (immigration, security) and a European dimension that concerns both economic and EU integration questions, as shown in the Figure below. The model is based on a Mokken scaling procedure of the policy positions of Greek political parties in the Voting Advice Application Choose 4 Greece.

Figure: Model of the Greek party system

Note: The Chart uses a scoring system between 0 and 4 for each dimension. The cultural dimension is not related to the economy, but instead indicates whether a party is traditional/authoritarian on socio-cultural issues (low score) or more liberal/cosmopolitan on these issues (high score). A higher score on the economic pro/anti-EU dimension indicates a party is anti-memorandum (and therefore anti-austerity). The parties are: Coalition of the Radical Left (Syriza); New Democracy (ND); Golden Dawn (XA); The River (Potami); Communist Party of Greece (KKE); Independent Greeks (ANEL); Panhellenic Socialist Movement (Pasok); Movement of Democratic Socialists (KIDISO); Democractic Left (DIMAR); Anticapitalist Left Cooperation for the Overthrow (ANTARSIA). For details of the methodology see the accompanying article by Simon Otjes and Tom Louwerse.

The reasoning behind this model is the following: since 2010 one cannot think of economic issues without considering the relationship between Greece and the EU. When Greece entered into its economic crisis and was no longer able to acquire financing from international financial markets, it required two bailout packages. These came with agreements (memoranda) between the Greek government and the Troika (EU, ECB and IMF) that dictated far-reaching budget cuts, acts of privatisation and welfare state reform. This dictated policy set the main lines of the Greek economic programme for the coming years.

What is more, accepting this policy became connected with remaining in the Eurozone and the EU, both in the public debate and at the negotiation table. It also linked support for the memoranda and Greece’s continued membership of the Eurozone to concrete economic measures, normally considered part of the left-right dimension. It was no longer possible to oppose austerity policies without raising the question of leaving the euro or the EU.

This division placed highly heterogeneous parties on the same side of the spectrum. Together with Syriza and the Independent Greeks on the side of those who opposed the memorandum were the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) and the extreme right Golden Dawn (XA). The centre-right New Democracy (ND), the centre-left Pasok and newly established centrist party The River were on the side of those who wanted to respect the memorandum.

The political debate during the election was mainly based on the economy, as people grew tired of continued austerity. The dominant line of conflict was not the left/right line of conflict, but rather a dimension that concerned both economic issues (the privatisations, budget cuts and reforms endorsed by the Troika) and the question of Greece’s role in the EU. From this perspective, a coalition government between the anti-austerity parties Syriza and ANEL not only makes sense, but is the one with the smallest policy distance on this dimension. With 13 seats, ANEL was also the smaller potential coalition partner available to Syriza, which ties in with the so called ‘minimum coalition size theory’ – i.e. by selecting the smaller party, Syriza ensured it would have more room for manoeuvre within the coalition.

At the same time, despite the focus on the economy at present, socio-cultural issues are no less pressing in Greece. Immigration, LGBT rights, and the church-state relationship play a major role in the country’s political debate and the new government will have to propose legislation in these areas. On these cultural issues we do find a type of traditional left-right division, but in Greece in 2015 the left and right divide no longer concerns economic issues (which have all been subsumed in the European dimension) but rather the division between those who favour a traditional, authoritarian and nationalist view of society and those who favour a more libertarian and cosmopolitan society. This comes very close to the cultural integration-demarcation dimension that Kriesi and others have proposed, but is entirely independent of the left-right division.

Cultural issues will be a major source of conflict for the Tsipiras cabinet: Syriza and ANEL stand on opposites sides of the spectrum when it comes to immigration, citizenship, gay marriage and civil rights. The libertarian proposals by Syriza may well be blocked by their coalition partner, as ANEL would not tolerate legislation so far away from the party’s main ideological lines.

This new model is a break from traditional understandings of the Greek policy space, but the growing influence of European actors over budgetary policy in all Eurozone member states may have the net effect of undermining the strength of the economic left/right dimension in party systems. As the EU sets the limits of economic policy across Europe, it becomes increasingly difficult to think of economic issues independent of the question of EU integration.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: (CC-BY-SA-ND-NC-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1LE6BHj

_________________________________

Alexia Katsanidou – GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences

Alexia Katsanidou – GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences

Alexia Katsanidou is a Senior Researcher at GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences. Her recent publications include ‘From valence to position: Economic voting in extraordinary conditions’ (with R. Nezi, 2014) in Acta Politica and ‘Multilevel Representation in the European Parliament ‘(with Z. Lefkofridi, 2014) in European Union Politics. Her research focuses on individual political behaviour and party politics in European and EU politics. She is currently working on changing societies in crisis.

Simon Otjes – Groningen University

Simon Otjes – Groningen University

Simon Otjes is a Researcher at the Documentation Centre Dutch Political Parties of Groningen University. He has published in the American Journal of Political Science, Party Politics and Electoral Studies. His research has examined political parties, party systems and spatial models of party positions in the Netherlands and the European Union.

Interesting. Here at the Centre for Research on Direct Democracy (Aarau, Switzerland), we have used similar methods (based on a combination of exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis and Mokken scale analysis) on the data generated from the users of choose4greece (rather than the positions of the parties as is the case with the above blog). We identify virtually identical dimensions: one economic dimension based on issues such as state control versus privatisation, austerity and Greek membership of the Euro, and one cultural dimension on issues like immigration, multiculturalism, the role of the Church, LGBT rights and drugs policy. Plotting the positions of users who identify with political parties on these two dimensions, moreover, we see that party supporters have similar positions that correspond rather well with those provided in the Figure.