Why does the European Commission at times propose legislative drafts that provoke Member State opposition, that introduce strikingly high or low standards, or that actively contradict each other? Miriam Hartlapp, Julia Metz and Christian Rauh present findings from a study of 48 legislative drafting processes. They argue that while the Commission is often thought of as a unified actor, there is substantial disagreement within the Commission over the nature of legislative proposals. They write that studying this conflict is key to understanding the policies the institution proposes for Europe.

Why does the European Commission at times propose legislative drafts that provoke Member State opposition, that introduce strikingly high or low standards, or that actively contradict each other? Miriam Hartlapp, Julia Metz and Christian Rauh present findings from a study of 48 legislative drafting processes. They argue that while the Commission is often thought of as a unified actor, there is substantial disagreement within the Commission over the nature of legislative proposals. They write that studying this conflict is key to understanding the policies the institution proposes for Europe.

The European Commission is at the core of the European Union’s political system and its quasi-monopoly on the initiation of legislation provides significant leverage over EU policy. Within its five-year terms, each Commission proposes up to 2,000 binding legal acts and thus crucially shapes the rules that govern the daily lives of more than 500 million European citizens.

Despite this centrality in EU governance, little is known about its internal position formation processes and inconsistent pictures of Commission agency dominate public and academic debates. The Commission, seen as a monolithic actor, is depicted as being either a technocratic body that adopts policies it deems to be efficient and effective problem solutions or an inherently political bureaucracy that constantly seeks to increase its competences vis-à-vis national governments.

These perspectives do not explain why Commission proposals sometimes give rise to formidable opposition from the member states and other stakeholders, such as those on the European Research Council. They also fail to explain why the Commission sometimes introduces strikingly high or strikingly low standards on closely related issues, as in the case of consumer policy, or even introduces proposals that actively contradict each other in substance, as occurred with the posting of workers and liberalisation of services directive.

Our book Which Policy for Europe? Power and Conflict inside the European Commission takes issue with monolithic conceptions of the Commission and challenges the unitary actor assumption. Chiefly, we assess how the policy position of an individual Directorate-General inside the Commission is formed with regard to a specific legislative proposal and how we can explain a Directorate-General’s policy choices. In addition we also analyse how deviating internal positions are coordinated and how we can explain the assertiveness of a Directorate-General in influencing the final Commission proposal’s substance.

Frequent internal conflict

We have analysed 48 legislative drafting processes that fall into the intersection of social and common market policies, research and innovation policies, and consumer policy adopted during the Prodi and Barrosso I Commissions (1999-2009). For each legal act, we reconstruct the complete position formation process inside the Commission, mainly relying on first-hand insights drawn from 150 structured interviews with Commission officials who had direct involvement. We find that while the outside view usually presents consensual decision-making in the College of Commissioners – obviously this makes sense to strengthen the Commission’s position vis-à-vis the Council and Parliament – the inside view on the process of position formation tells quite a different story.

First, far-reaching policy choices are often taken at the Commission’s administrative level, rather than at the political level of the College of Commissioners. Second, inside the Commission intense interactions and substantial conflict are the norm rather than the exception. This makes position formation a time-consuming process (on average 25.6 months) and offers multiple entrance points for external interests, such as member states, organised interests, or experts, as well as for other affected services.

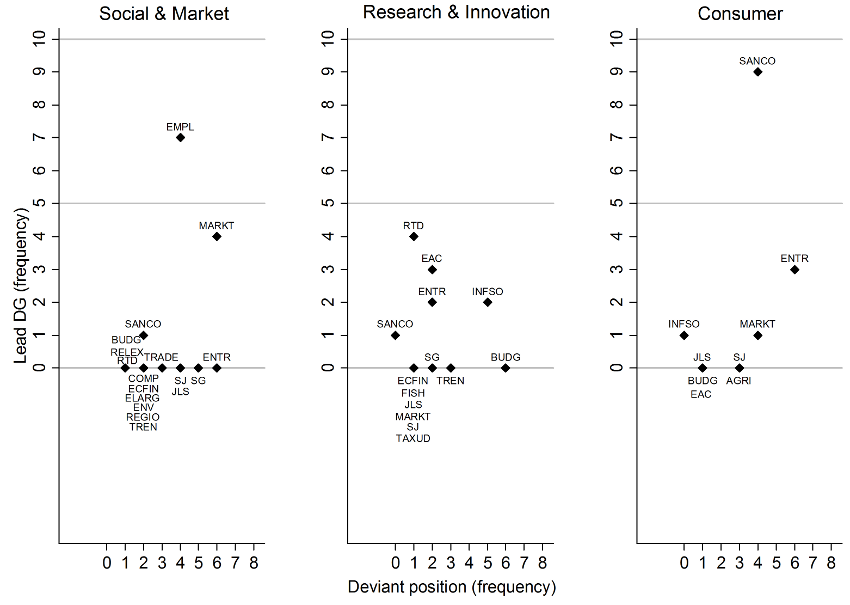

In fact, in more than three quarters of the analysed cases we found substantially deviating positions between different administrative units inside the Commission. Typically, three to four Directorates-General disagreed and did so across rather stable conflict lines, as the Figure below shows. For example, legislation in the area of social and internal market policies often evoked conflict between the Directorates-General for Employment (EMPL), for the Internal Market (MARKT), and for Enterprise and Industry (ENTR).

Figure: Conflict within the Commission by policy areas (click to enlarge)

Note: The three charts indicate the degree of conflict between Commission Directorates-General in three policy areas. The vertical axis indicates the frequency with which a particular Directorate-General was the lead actor on legislation within the policy area (the higher the number the more active they were). The horizontal axis indicates how frequently each Directorate-General took a ‘deviant position’ (i.e. a position which deviated from the ideal position of the lead actor). Directorates-General which appear on the right of a chart have accordingly challenged the formally responsible department more often in the respective policy area. For a full list of the Directorates-General and their abbreviations see here.

Three ideal types of position formation

In essence, the policy substance of a Commission proposal depends on which Directorates-General and/or Commissioners were involved and who proved to be most powerful. Consequently, interaction inside the Commission needs to feature much more prominently in our explanations of the policies proposed for Europe.

With this stated, what are the different substantial positions, conflict lines and power resources inside the Commission? We have analysed these at length, with the general conclusion being that the Commission neither follows member state interests nor focuses on effective problem solutions all of the time. Rather, different types of agency constantly co-exist inside the Commission. These can be summarised into three ideal-typical process patterns.

First, in a technocratic position formation process, the internal Commission actor’s most important goal is finding the optimal policy solution. Expertise is the bureaucrat’s most relevant source of influence. For example, the extant acquis and ECJ jurisprudence are important sources of legal consistency and external views are welcomed if they offer efficient solutions or templates. However, as sectoral policy-portfolios might differ in their preferred problem solutions, interaction between Commission services may emerge, which then resembles a coordination game where all actors expect common spoils and adjust their positions on the basis of argumentative processes.

Second, this view contrasts with Commission actors who enter position formation with the goal of retaining or expanding their competences and/or budget vis-à-vis the national level or in turf wars with other Commission services. Positions are often best explained by the anticipation of future decision-making in view of aggregate national interests. Stakeholders and interests are granted influence where they deliver support and are deemed necessary to safeguard competence extension. Differing sharply from technocratic processes, interaction resembles a zero-sum game where one Directorate-General ‘wins’ and another ‘loses’, with Directorates-General exploiting all available resources strategically to this end.

Finally, processes are equally political under the policy-seeking type. The difference here is that actors enter the process with ideological goals and use their offices to accomplish them. Policy positions and internal assertiveness result from a pursuit of a normative fit between actor ideologies and the contents of the legislative proposal. This means that stakeholder access follows a so called ‘neo-pluralist’ pattern and that a Directorate-General may mostly care about those member states with an ideologically congruent policy. Conflict is typically overcome by building external and internal alliances held together by the allies’ beliefs and views: for example along close party-political stances among Commissioners or among like-minded services.

Specific processes might share different ideal typical features or might switch from one type to the other in one process. In explaining what mediates between the different process-types, we find that policy context matters: High uncertainty about policy consequences suppresses internal competence-seeking but does not necessarily lead to more technocratic decision-making. On the contrary, uncertainty sometimes made internal actors rely on normative heuristics, thus resulting in policy-seeking processes. A high public salience of the regulated issues, in turn, made both competence-seeking and ideological considerations more relevant. In light of rising public attention on European decisions, we thus expect an increasing potential for more political processes in the future.

Which policy for Europe?

If different process types exist, there are also different leverage points for influencing policy substance. To illustrate the argument, consider the question whether internal position formation contributes to explaining the frequently asserted predominance of market-liberal positions over more interventionist approaches in European legislation. Under the technocratic model, more interventionism can be expected from unbiased expertise, such as from balanced access to the Commission’s expert groups or the creation of more interventionist legal precedents.

Under the competence-seeking model, Commission positions on the market-interventionism dimension may be based on the extent of competence transfers they generate. Thus, restructuring the internal distribution of responsibilities could stimulate departure from the extant acquis. Moreover, reducing the power resources of the lead department could also ensure more balanced EU policies.

Under the policy-seeking model, finally, those aiming at more balanced (in the sense of less liberal) market regulation should mainly focus on the selection of the Commission’s leading personnel and its ideological orientation. This holds particularly for the Commission President who – via the Commission’s Secretariat General – controls the balancing of coordination processes and the assignment of lead departments. Combined with our insight that a policy-seeking Commission is indeed responsive to the public, open political competition for the leading positions in the Commission could thus be a key lever under the policy-seeking model.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1DW5VvN

_________________________________

Miriam Hartlapp – Leipzig University

Miriam Hartlapp – Leipzig University

Miriam Hartlapp is Professor for Multilevel Governance at Leipzig University.

–

Julia Metz – University of Bremen

Julia Metz – University of Bremen

Dr Julia Metz is Senior Researcher in the research area “Governance and Organizational Studies” at the University of Bremen.

–

Christian Rauh – WZB Berlin Social Science Center

Christian Rauh – WZB Berlin Social Science Center

Dr Christian Rauh is a Research Fellow in the Global Governance department of the WZB Berlin Social Science Center.