Spain will hold local and regional elections in the coming months, with a general election scheduled for later in the year. Paul Kennedy writes on the state of play in the Spanish party system ahead of the elections, where a surge in support for both the left-wing Podemos, and the centrist Ciudadanos, poses a threat to the country’s two traditional mainstream parties, the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party and People’s Party.

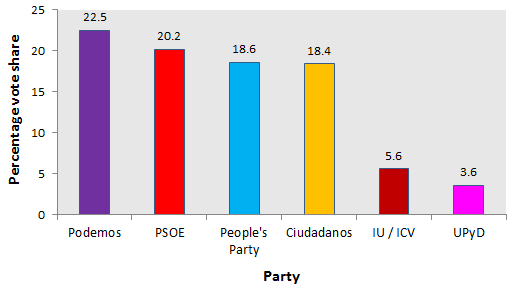

On the eve of the first of a series of key elections due to take place in Spain throughout 2015, the March Metroscopia poll carried out for El País indicates that no less than four parties are separated by just four per cent of the vote (as shown in the chart below). Regional elections in Andalusia on 22 March are followed two months later by local and regional elections throughout the country. September will witness regional elections in Catalonia, followed by the general election, due to be held before the end of the year.

Chart: Predicted vote share in 2015 Spanish general election

Note: Figures are from the March 2015 Metroscopia poll for El País. For more information on the parties/alliances see: People’s Party (PP); Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE); Podemos; United Left (IU); Ciudadanos (C’s); Union, Progress and Democracy (UPyD).

The likelihood of the need for deals between the leading parties following the general election has provided additional justification for the relative newcomers on the Spanish political scene, Podemos (‘We Can’) and Ciudadanos (Citizens – C’s) to delay clarification of their respective policy programmes. Whilst, on the left of the political spectrum, the PSOE and United Left (IU) appear to have most to fear from the rise of Podemos, the breakthrough of Ciudadanos (Citizens) as a significant player on the Spanish (as opposed to the Catalan) political scene has similarly disconcerted Union, Progress and Democracy (UPyD) and the governing People’s Party (PP).

Ciudadanos’s growing salience has been one of the most striking developments over recent months. Founded a decade ago in reaction to the rise in Catalan nationalism, the party increased its representation within the Catalan Parliament from three to nine seats at the most recent regional elections in 2012 and obtained two seats at the European elections held in May 2014. On the centre-right of the political spectrum, its economic programme, under the tutelage of LSE Economics Professor Luis Garicano, emphasises the need for further liberalisation, or what the party has dubbed as ‘sensible change’ (cambio sensato).

The issue of corruption has also figured highly in the party’s discourse as it hopes to attract votes from former supporters of the People’s Party government, whose political credibility has been undermined by numerous corruption allegations. In the above-mentioned opinion poll, Ciudadanos’s Albert Rivera was the only leader of a major political party capable of obtaining a positive ranking (more approval ratings than disapprovals).

Whilst Ciudadanos has been at pains to stress its centrist credentials, Podemos has sought to tone down its leftist rhetoric. Most notably its leader, Pablo Iglesias, has identified his party with social democracy, apparently targeting the electoral space hitherto occupied by the PSOE. Ideological repositioning has not been Podemos’s sole concern over recent months. With an important element of the party’s appeal being based on criticism of the alleged corruption of the political class (casta), Podemos has every reason to ensure that it keeps its own house in order.

Of recent concern has been the revelation that Iglesias’s lieutenant, Juan Carlos Monedero – like Iglesias a politics professor at Madrid’s Complutense University – was paid 425,000 euros in 2013 via a private company he had set up that same year for work carried out in 2010 as a consultant to the governments of Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia and Nicaragua concerning the introduction of a single currency in the region. Opponents have claimed that the money was used to finance Podemos media items. Monedero submitted a related income tax payment of 204,000 euros in January 2015, a sum which included a 15 per cent penalty for late payment.

With respect to the Andalusian regional elections to be held on 22 March, a Metroscopia regional poll published a week before the election indicated a victory for the PSOE, albeit with the party gaining 3 per cent less of the vote than in the previous election held in 2012 (39.5 per cent). The People’s Party, which obtained the highest percentage of the vote on that occasion (40.7 per cent), is forecast to see its vote decrease by 15 per cent. In third place is Podemos (14.7 per cent) followed by Ciudadanos (11 per cent) and United Left (8.5 per cent).

Whilst the Andalusian branch of the PSOE, led by Susana Díaz, has ruled out any post-election deals with the PP or Podemos, it remains to be seen whether the mutual recrimination which brought about an end to the PSOE’s previous agreement with United Left prevents a reprise of the deal following polling day, or whether Ciudadanos, partly aided by its ideological ambiguity, offers the PSOE an alternative partner in government.

Should the PSOE under Díaz’s leadership prove capable of re-establishing its dominance over all other parties, thereby underlining the region’s status as a historic Socialist stronghold, there may well be calls from within the PSOE for Díaz to take over the party’s national leadership, particularly if the current incumbent, Pedro Sánchez, who has enjoyed a mixed record to date, leads the PSOE to a less than satisfactory result at the general election at the end of the year.

A final point worth noting is the relative youth of the majority of Spain’s major party leaders, which could prove a defining feature of the Spanish political scene in this key election year. Youngest of all is United Left’s Alberto Garzón, who is 29, followed by Ciudadanos’s Albert Rivera, who is 35, a year younger than Podemos’s Pablo Iglesias. Whilst the PSOE’s Pedro Sánchez is 43, three years older than Andalusian Socialist leader Susana Díaz, exceptions to the rule are provided by Union, Progress and Democracy’s Rosa Díez, who is 62 and the prime minister himself, Mariano Rajoy, who was born in 1955.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

Is Spain heading for a four party system?

Answers is not.

To have 4 parties is temporary in Spain politics. To be rough, spanish political system is rotten, and a reaction is to have 2 new parties heading on polls.

But Spanish system is designated to have only 2 major parties. For its parties law, how presence in media is designated by another law or how electoral system works. Maybe this time they can have four major parties, but next time again they will ahve onl 2 major parties. Which of them ?, this is what have to be seen.

Also something I will like to add. Have you seen any tranlation of this percentages to MP ? Not. Because at those percentages – using spanish electoral system – a minor variation can be translated on 50 MP more or less for a single party. And because percentages across different spanish territories diverge a lot and electoral system magnifies those differences.

My guess is PP still heads comfortably in expected MP.

I interviewed one of Podemos’ founders, Luis Alegre, last week in Madrid. Our translated conversation can be found at http://fourchat.wordpress.com and he touches on many of the points raised here. Thanks, Eddie.