The UK held a referendum in 2011 on adopting an Alternative Vote (AV) electoral system for general elections, which was rejected by a substantial majority of the British public. Chris Hanretty assesses how AV might have affected the 2015 UK general election. He notes that while the Conservative Party opposed AV during the referendum, the latest seat projections suggest they would have been in line to gain more seats than under the current first past the post system.

The UK held a referendum in 2011 on adopting an Alternative Vote (AV) electoral system for general elections, which was rejected by a substantial majority of the British public. Chris Hanretty assesses how AV might have affected the 2015 UK general election. He notes that while the Conservative Party opposed AV during the referendum, the latest seat projections suggest they would have been in line to gain more seats than under the current first past the post system.

In 2011 the Conservative Party campaigned against the Alternative Vote. They believed that the system would benefit centrist parties like the Liberal Democrats, who would receive “second preferences” from both Labour and Conservative voters. In 2015, the Conservatives would very much like to benefit from the “second preferences” of UKIP voters. They hope to turn those second preferences into first preferences – but were the Conservatives wrong to oppose AV, and would this electoral system have benefitted them were it in place for this election?

To answer this question, I’ve looked at the British Election Study (BES). The BES asks voters to take each party in turn, and say how likely it is on a zero to ten scale that they would ever vote for this party. This question – known in the trade as a propensity-to-vote question – can be turned into a preference ordering, so that the party with the highest score is ranked first, the party with the next-highest score is ranked second, and so on.

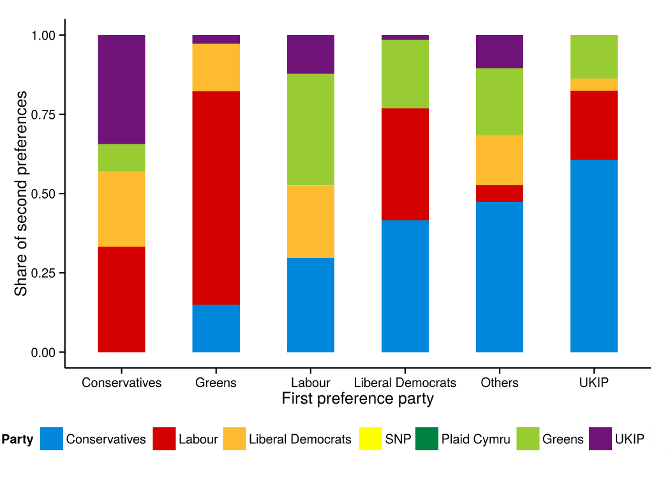

We can then examine the second preferences of supporters of different parties, supporters located in different countries, and supporters in seats held by different parties. Here, for example, are the second preferences of supporters of different parties averaged over English respondents in Labour-held constituencies:

Figure: Second preferences of supporters of different parties in Labour-held constituencies in England

Source: British Election Study

Source: British Election Study

The chart shows that those who give their first preference to UKIP are more likely than supporters of any other party to give their second preference to the Conservatives. On the left, the vast majority of Green supporters give their second preference to Labour. We can produce graphs similar to this for voters in Scotland in Labour-held seats, or voters in England in Conservative held seats. There are some differences – UKIP voters in Labour-held seats are much less likely to give their second preferences to the Conservatives than are UKIP voters in Conservative-held seats. But armed with these second preferences, we can approximate what might have happened under AV.

(Technical note: I’m going to ignore the problem of third, fourth, and fifth preferences, and assume that the remaining preferences of, say, UKIP supporters who give their second preference to the Greens are similar to the second preferences of those who start off with the Greens).

When we use these second preferences in this way, what do the results look like?

- Conservatives: 311 (281 seats in forecast)

- Labour: 244 (267 seats in forecast)

- Liberal Democrats: 26 (26 seats in forecast)

- SNP: 47 (51 seats in forecast)

- Plaid Cymru: 2 (4 seats in forecast)

- Greens: 1 (1 seats in forecast)

- UKIP: 0 (1 seats in forecast)

In this exercise, the Conservatives do end up benefitting from AV. Of the 228 seats won by the Conservatives after the first round of voting, fully 128 are the result of vote transfers from UKIP supporters. These transfers would gift the Conservatives the keys to Number 10. The losers from AV are the Marmite parties – UKIP, the Scottish National Party, and Plaid Cymru. Labour loses – but primarily because it is pipped to the post by the Conservatives in a number of seats.

It’s impossible to know whether voter and party strategies would have remained the same if the electoral system had changed. The UKIP threat might have been pre-empted, leading to a more centrist campaign on certain issues. After all, a world in which the AV referendum succeeds is a world in which the Liberal Democrats are a far more successful governing party. As with other attempts to work out the effects of other electoral systems, we can only give indications of likely outcomes – a parliamentary majority has to take the plunge in order to find out how it would really work.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: Figures are accurate as of 5 May 2015. This article originally appeared at the LSE’s general election blog and gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: CGP Grey (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1KhmSAl

_________________________________

Chris Hanretty – University of East Anglia

Chris Hanretty – University of East Anglia

Chris Hanretty is a Reader in Politics at the University of East Anglia.