Once negotiations over the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) are completed, the agreement will need to be approved in the European Parliament before it can enter into force. But would TTIP be able to secure enough support in the current parliament? Pieterjan Vangerven and Christophe Crombez present an analysis of the recent decision to postpone the debate on a resolution on TTIP in the European Parliament on 10 June. They note that the vote on the postponement indicates the centre-right to be supportive of TTIP, the left and far-right to be opposed, while the centre-left is deeply divided. Nevertheless, the ideological basis for MEPs’ voting behaviour suggests that negotiators should be able to achieve an agreement that attracts support from sufficient numbers of MEPs who abstained in the 10 June vote.

Once negotiations over the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) are completed, the agreement will need to be approved in the European Parliament before it can enter into force. But would TTIP be able to secure enough support in the current parliament? Pieterjan Vangerven and Christophe Crombez present an analysis of the recent decision to postpone the debate on a resolution on TTIP in the European Parliament on 10 June. They note that the vote on the postponement indicates the centre-right to be supportive of TTIP, the left and far-right to be opposed, while the centre-left is deeply divided. Nevertheless, the ideological basis for MEPs’ voting behaviour suggests that negotiators should be able to achieve an agreement that attracts support from sufficient numbers of MEPs who abstained in the 10 June vote.

On 10 June the European Parliament (EP) was scheduled to vote on a resolution on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). Such resolutions on trade agreements are non-binding, but often indicate what agreements the EP is willing to approve in the end.

However, EP President Martin Schulz decided to postpone the vote due to the large number of amendments proposed. More time was needed for the EP’s international trade committee to assess the amendments, and for Schulz’s own political group of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) to overcome its internal divisions on the issue. The EP subsequently decided to postpone the debate on the resolution as well, with MEPs who favour TTIP voting for postponement, presumably to avoid the chaos and uncertainty that could result from a debate on hundreds of amendments. In the end, the vote took place on 8 July.

The vote on the postponement was highly political, and the EP was deeply divided. Of the 401 MEPs who participated in the vote, 183 (46 per cent) voted in favour of postponement, whereas 181 (45 per cent) opposed it, and 37 (9 per cent) abstained. As a simple majority sufficed, the debate was indeed postponed. A coalition of Christian-Democrats (EPP), Conservatives (ECR) and Liberals (ALDE) won the close vote and the result suggests that eventual approval of TTIP is far from certain.

But what determined the stances taken by MEPs during the vote? Was voting behaviour shaped by their ideology or nationality? Moreover, what conclusions can be drawn with regard to the eventual vote on TTIP when the negotiations are concluded and the agreement is placed before the EP?

Party groups and the 10 June vote on TTIP

Typically ideology is found to drive voting behaviour in the EP rather than nationality. Since free trade with the United States can be expected to affect member states quite differently, it would not be surprising, however, to find that nationality played an important role in the vote on TTIP as well.

When we look at the numbers our first observation is that only 53.5 percent of MEPs (401 of the 750 MEPs at the time of the vote) participated in the vote – far below the average EP participation rate of close to 90 per cent. Thus, analysing who did not vote can be as worthwhile as studying who voted in favour or against. Those who expressed their preferences in this close vote are not likely to change their views on TTIP. The MEPs who abstained, did not vote or were absent will thus make the difference in future votes.

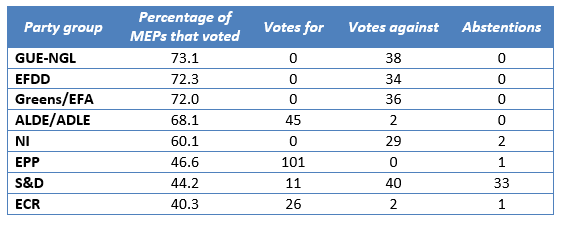

Table 1 shows that participation was especially low among the three largest political groups (EPP, S&D and ECR), with participation rates in the 40s. This is quite unusual: the EPP and S&D typically have among the highest participation rates. We will return to the analysis of participation rates below. For the moment it suffices to keep in mind that participation was extraordinarily low among MEPs from the main centre-right and centre-left pro-integration groups.

Table 1: Participation rates and votes by party group

Note: NI refers to MEPs that are not part of any official group. For more information on the groups in the Parliament, see: European United Left–Nordic Green Left (GUE-NGL); Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD); The Greens–European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA); Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE); European People’s Party (EPP); Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D); European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR).

Turning to the way MEPs voted, Table 1 also illustrates that political groups displayed a large degree of internal unity, except for the S&D. The MEPs to the left of the S&D (Greens/EFA and GUE-NGL) and to the right of the ECR (EFDD and the mostly extreme-right non-attached NI) voted against, except for two abstentions amongst the NI MEPs (two Greek Golden Dawn MEPs who remain non-attached after the more recent formation of the extreme-right ENF group).

None of the participating EPP MEPs voted against, with just one of them abstaining. Nearly all ECR and ALDE MEPs voted in favour as well. The Table further shows that the vote divided the S&D down the middle. Almost half of S&D MEPs participating in the vote voted against postponement of the debate on the resolution, even though their group leaders had asked for and obtained the postponement of the vote on it. Fewer than 15 per cent of participating S&D MEPs voted in favour, with the remaining S&D MEPs abstaining. The vote tally thus shows the centre-right supportive, the left and extreme-right opposed, and the centre-left deeply divided.

Explaining the positions taken by MEPs on TTIP

To analyse the vote in more detail and assess what determined the votes of MEPs, we have looked at the impact of ideology and nationality using a simple logit regression model with party group and country fixed effects. We found that party groups all significantly influence voting behaviour, which is not surprising given the vote tallies we presented above. However not all member states significantly affect voting behaviour. This finding may be partially due to the fact that there are fewer observations per member state, but nonetheless this may be a first indication that ideology outweighed nationality. Belgian MEPs were on average significantly more in favour, whereas MEPs from France, Italy, Poland, Romania, Spain and five smaller member states were significantly less in favour.

The impact of an MEP’s party group and member state on their voting behaviour can be further assessed by replacing the party group and member state dummies with continuous variables that measure party group and member state characteristics. We have used information from the ParlGov dataset on the ideological positions of the political groups, both on the left-right and the anti-pro-EU dimensions, to capture the party group effects on MEPs voting behaviour. The data on the locations of party groups are those of the seventh parliament. These may differ a little compared to the eighth parliament, but can be expected to be roughly the same.

To capture the effect of an MEP’s nationality on voting behaviour we also used two variables. The first variable relates to a member state’s trade relations with the US. In particular we use the sum of the imports from and exports to the US divided by the member state’s GDP as the variable measuring the importance of the US as a member state’s trading partner. The second variable measures a member state’s public support for TTIP, as recorded in the November 2014 Eurobarometer Survey.

We first compared yes-votes to all other alternatives, that is, no-votes, abstentions, MEPs who did not vote, and MEPs who were absent. This analysis indicated that the likelihood of a yes-vote increased the more right-wing and pro-integration the MEP’s party group was, and the more important the US was as a trading partner for the MEP’s member state. The marginal effect of the importance of trade is low though when compared to the effect of the ideological preferences. When we compared yes-votes to no-votes only, US trade was no longer significant. The logit regressions thus indicate that party group preferences were more important than member state characteristics for MEPs when voting.

For a more complete analysis we also ran an ordered logit model. In this model we treated MEPs who did not vote or were absent as abstentions. Our results indicate once again that the party group variables determined MEPs’ votes. Both the left-right and pro-anti-EU preferences of the party groups had significant effects on the votes.

Trade flows with the US did not have an econometrically significant effect. Member state public support for TTIP did, however. Since public support did not have a significant effect in the logit models, the effect we obtained in the ordered logit model suggests that public support explains MEPs’ decisions on whether to abstain or cast a negative vote. In the logit models abstentions were excluded or treated as no-votes.

Finally we ran a logit regression model to study what determined MEPs’ decisions to participate or avoid participating in the vote. We found that MEPs from party groups that are pro-EU integration and from member states with high public support for TTIP were significantly more likely to abstain. Trade with the US also had a positive effect on the probability of abstention, but it was economically insignificant. The left-right position of MEPs’ political groups had no significant effect. This result further shows that member state public support for TTIP played a role in MEPs’ decision over whether to participate in the vote, whereas party group characteristics determined whether MEPs voted yes.

In sum our analysis shows that party group preferences explain MEPs’ votes on the postponement of the debate on the TTIP resolution, with MEPs from pro-EU groups on the right more likely to vote in favour. The decision to abstain from voting was driven by member state public support and party group preferences on the EU, however, with MEPs from member states with high support for TTIP and pro-EU party groups more likely to abstain.

These conclusions suggest that even though the vote was extremely close, TTIP negotiators should be able to achieve an agreement that attracts support from sufficient numbers of MEPs who abstained in the vote on 10 June, provided that they compromise to that effect.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Parliament (CC-BY-SA-ND-NC-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1CFFGuz

_________________________________

Pieterjan Vangerven – University of Leuven

Pieterjan Vangerven – University of Leuven

Pieterjan Vangerven is a PhD Candidate in Political Economy at the University of Leuven.

–

Christophe Crombez – University of Leuven / Stanford University

Christophe Crombez – University of Leuven / Stanford University

Christophe Crombez is Professor of Political Economy at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven (since 1994). He is also Consulting Professor at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University (since 1999). His research focuses on EU institutions and their impact on EU policies, EU institutional reform, lobbying in the EU, and electoral laws and their consequences in parliamentary political systems.

Interesting research which ignores one key variable. The vote to postpone the debate was held first thing in the morning on the 10th of June (and not during a regular voting session) and organised at short notice, hence many MEPs simply weren’t out of bed yet.