Croatia will hold a parliamentary election on 8 November. Ahead of the vote, Tena Prelec and Stuart Brown take a final look at the election campaign, providing an overview of the country’s party system, the latest polling, and some of the key contextual factors that could play a role in determining the outcome.

Croatia will hold a parliamentary election on 8 November. Ahead of the vote, Tena Prelec and Stuart Brown take a final look at the election campaign, providing an overview of the country’s party system, the latest polling, and some of the key contextual factors that could play a role in determining the outcome.

Croatia goes to the polls on 8 November in the country’s first parliamentary election since joining the EU in 2013. The election will take place against the backdrop of the ongoing refugee crisis, which has had a significant impact not only on domestic politics within Croatia, but also on the country’s relations with its neighbours. The Croatian government’s policy of allowing refugees to pass quickly across its territory has drawn heavy criticism from bordering states: notably Hungary, which closed its border with Croatia in October, and Slovenia, where many refugees were subsequently redirected. The crisis has also added to existing tensions between Croatia and Serbia.

Recent Croatian elections have tended to be dominated by excessively combative campaigning from the country’s two largest parties – the Social Democratic Party of Croatia (SDP), which is currently in government, and the opposition centre-right Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) – and the 2015 elections have continued this trend. Both parties, which contest the elections as part of electoral coalitions – Croatia is Growing for the SDP and the Patriotic Coalition led by the HDZ – have fought an increasingly confrontational campaign, largely dodging key political issues in favour of personal attacks on each other.

The latest opinion polling points to a narrow lead for the coalition led by the HDZ, albeit by a much narrower margin than it enjoyed earlier in the year. Nevertheless some seat calculations have suggested that the race is virtually a dead heat, with either side capable of emerging in front. Although the SDP’s coalition won a resounding victory in the last election in 2011, securing a majority in parliament, the previous election in 2007 was an extremely close contest, with the HDZ’s coalition, led by former Croatian Prime Minister Ivo Sanader, managing to make up several percentage points in the final weeks to finish ahead.

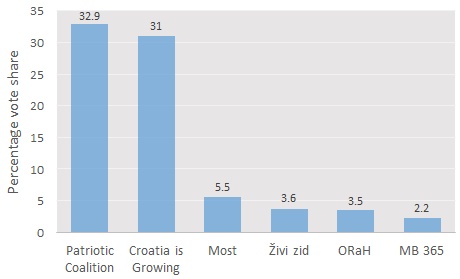

Chart: ‘Poll of polls’ for the 2015 Croatian parliamentary elections

Note: This chart is intended for illustrative purposes and is not an attempt to predict the outcome of the election. It applies equal weighting to the published opinion polls conducted by the Ipsos Puls agency and Promocija Plus in the last month of the campaign. For more information on the electoral coalitions/parties see: Patriotic Coalition (led by Croatian Democratic Union – HDZ); Croatia is Growing (led by Social Democratic Party of Croatia – SDP); Živi zid (ŽZ); Bridge of Independent Lists (Most); Sustainable Development of Croatia (ORaH); MB 365.

Given the tight nature of the polling, it remains impossible to predict how the final results might play out. This is particularly the case in light of the surprise win for Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović in Croatia’s presidential election held at the start of the year. Defying the projections of opinion polls, Grabar-Kitarović, representing the HDZ, became the country’s first female President, narrowly ousting the SDP’s Ivo Josipović. Whether this represented the first step in a general shift to the right for the country will only be known following the parliamentary vote.

The SDP and the HDZ

Despite the country’s accession to the EU in 2013, Croatia’s Prime Minister, Zoran Milanović, has largely failed to live up to expectations following the SDP’s victory in 2011. The Croatian economy has been mired in a long recession during this period, with the government’s fiscal consolidation policies proving unable to generate a recovery, albeit with some modest growth of 0.8 per cent now expected for 2015 as a whole.

The SDP has also had to deal with a number of internal conflicts since 2011, with Milanović opting to fire the country’s Finance Minister, Slavko Linić, in 2014. Moreover, there is a widespread perception that the government failed to push through necessary reforms aimed at tackling corruption after its election victory – one of the key aspects that won the SDP support in 2011 – and Milanović’s personal standing with the electorate dropped substantially as a result.

Yet the belated and relatively timid upturn in growth has nevertheless come at an opportune moment for the SDP, with Milanović able to claim that the country is beginning to see the fruits of his reforms and that another period in office is required to gain the full benefits from his economic strategy. As such the Prime Minister, bolstered by the campaigning advice of American PR expert Alexander Brown, has presided over something of a comeback, though it remains to be seen whether it will be enough to secure another election victory.

Meanwhile the HDZ has experienced a tumultuous period since 2011, following a major corruption scandal in which a Croatian court found both Sanader and the HDZ as a whole guilty of siphoning off funds from state-run companies. From this low-point, the party’s leader, Tomislav Karamarko, has managed to bring around a revival in fortunes for the party, playing on Milanović’s poor early performance in government, the SDP’s apparent problems in keeping their ranks together, and a general feeling among the electorate that the country is not being governed appropriately. Grabar-Kitarović, who adopted the role of a hardline patriot during her presidential campaign, but has since reverted to more moderate positions, may also have positively influenced the HDZ’s support.

In their own way, then, both the SDP and HDZ have endeavoured to recover from difficult positions by exploiting the faults of their rivals. While the HDZ has capitalised on the SDP’s mistakes in office, Milanović’s electoral strategy has relied in no small part on emphasising the HDZ’s dubious record on corruption. The HDZ was also strongly critical of the government’s response during the initial phase of the refugee crisis, calling for a more hardline approach and the possible closing of borders. In recent weeks, however, Milanović and the SDP appear to have used the issue to their advantage, with the government’s more lenient response chiming with some sections of Croatian society.

In terms of the campaign itself, a significant controversy has centred around the lack of a televised debate. The public broadcaster, HRT, decided to cancel the pre-electoral debate involving party leaders scheduled for 6 November after complaints from minor parties to whom the invitation was not extended, and the subsequent ruling of the state electoral committee that the editorial decision to exclude those parties was questionable. A crucial aspect in the decision, however, was Karamarko’s refusal to take part in a direct confrontation with Milanović.

New challengers

The constant blame game between the two major parties has had a wearying effect on the electorate. Most voters have simply had enough of the antagonistic rhetoric and stark bipolar campaigning that has dominated Croatian politics since the country’s independence in 1991, and it is therefore unsurprising that some support has emerged for embracing a third option beyond the SDP and the HDZ.

At the European Parliament elections in May 2014, the green party ORaH (a splinter party that broke away from the SDP, headed by the former Minister of the Environment Mirela Holy) won a surprise seat. During the presidential elections last December, the anti-establishment party Živi zid (Human Blockade), led by the 25-year-old Ivan Sinčić, also had a good showing, despite lacking any previous political experience.

Both ORaH and Živi zid have failed to build on their success, but a new challenger has emerged during the 2015 election campaign: Most Nezavisnih Lista (Bridge of Independent Lists) – typically shortened to ‘Most’. The party was founded in 2012 by the former mayor of the Dalmatian town of Metković and physician Božo Petrov, but operated solely at a regional level until now. Most’s credibility has been strengthened by the recruitment of Ivan Lovrinović, an economics professor and prominent critic of the Croatian establishment’s policies. Their electoral programme centres on promoting economic growth, while transport, ecology, food security, energy and the reform of the judiciary are presented as key themes.

Polling for the party has varied significantly, but the most recent polls indicate that Most could potentially secure somewhere in the region of eight of the 151 seats in parliament – which would likely crown them as kingmakers. In recent days, both the HDZ and the SDP have expressed their interest in a coalition with Most, but to no avail: the party has repeatedly stated that it will refuse to side with either party in parliament. The newcomers present themselves as a clear third way to what they dub the ‘HDZSDP’, indicating that they do not see much difference between the two mainstream parties. Judging by the comments on their Facebook page, though, it would appear that not all of Most’s supporters agree with this policy: some would like to see them taking part in a government coalition and instigate change from the inside.

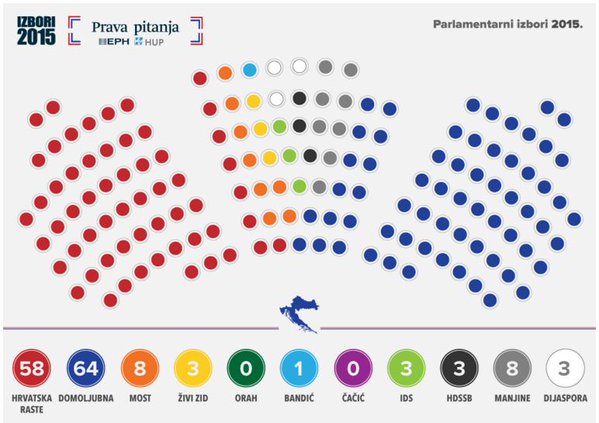

Figure: Predicted seat allocation in the Croatian parliament on 6 November (Jutarnji)

Note: Figure is reproduced from Jutarnji List

The roots of Most are in Dalmatia, a region which was heavily hit by the war in the 1990s and where nationalistic sentiments are still very high: for this reason, there are speculations that the party’s positions are closer to the right than they are to those of the SDP, despite recent skirmishes with the HDZ. Another important consequence of Most’s success could be the potential to wipe out other minor parties if it can mobilise sufficient support, given the five per cent electoral threshold required for representation in parliament. ORaH could well be one of the casualties.

Meanwhile the former mayor of Zagreb, Milan Bandić, has entered the race as an independent candidate and will be hoping to mobilise support around a similar platform of opposition to the SDP and the HDZ. In a typically populist manner, he has summed up his views on the mainstream parties by observing that “it does not make any difference whether we die of black death or of cholera: it is better not to die at all”. Former President Ivo Josipović, former Prime Minister Jadranka Kosor, and former university dean Josip Kregar have also joined forces in a new party, Forward Croatia. Both are hoping to obtain one parliament seat.

It is also worth noting the Istrian Democratic Assembly (IDS), a long-standing regional player in Croatian politics. The left-leaning, largely Italian bilingual peninsula of Istria has always had a distinct identity and it remains the wealthiest region in Croatia. All three parliament seats for Istria are expected to be won by the IDS.

The diaspora

One final important element in the elections is the role of the Croatian diaspora. With an extremely tight contest predicted, the significance of the diaspora is likely to increase. Although there are numerous Croatian communities presently living across Europe and elsewhere around the world, the bulk of the diaspora is located in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Traditionally, the Croatian diaspora in Herzegovina has been strongly supportive of the HDZ and their votes could be crucial in swinging the outcome of the vote. If the HDZ does win the elections, it is to be expected that voices calling for a third entity within Bosnia and Herzegovina will increase, as for the Croatians living in the country there will then be a stronger connection with the ‘kin-state’. This would not be good news for Bosnia: next month marks 20 years after the Dayton agreement and the country is still sharply divided along ethnic lines.

Who will win?

While the razor-tight polling makes concrete predictions impossible, Karamarko’s Patriotic coalition will undoubtedly go into the election as the favourite. The HDZ has an extremely solid voting base, especially in the eastern region of Slavonia, in Dalmatia and among the diaspora. The party’s capacity to mobilise supporters was apparent in a gathering organised on 5 November in the Zagreb Arena, attended by over 20,000 Croats from the capital and beyond. During the meeting, Karamarko embraced the opportunity to further deride his opponents, stating that “I would really like to know whether they are able to summon up as many people”.

While much has been made of the SDP’s use of American PR experts, the right, though perhaps less sophisticated, arguably has equally effective publicity methods at its disposal. Recent features in the widely-read female magazine Glorija have presented Karamarko with his second wife Ana getting married and cradling their newborn. Ana has recently been accused of taking part in her husband’s controversial energy deals with Russian and Finnish firms, but these accusations have effectively been countered by the carefully crafted image of a stable family.

However, even if the HDZ’s coalition does manage to win the most support in the election, it is highly unlikely that any coalition will manage to secure the majority of seats required for the formation of a government. Negotiations will then begin and it is safe to predict that certain natural alliances will form in the aftermath: Istria’s IDS are expected to side with the SDP’s coalition, while the diaspora seats will most likely end up with Karamarko’s Patriotic coalition. Meanwhile Slavonia’s regional party, HDSSB, has already announced that it is ready to support the winning government formation in exchange for the Ministry of Agriculture. The big unknown is Most: if the newcomers really manage to obtain the kind of support indicated in some of the latest polls then much will depend on how they choose to play their cards.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1NiiEIQ

_________________________________

Tena Prelec – LSE / University of Sussex

Tena Prelec – LSE / University of Sussex

Tena Prelec is an Editor of EUROPP. She is a doctoral researcher at the University of Sussex and keeps an active involvement in the LSE’s research unit on South Eastern Europe, LSEE.

–

Stuart Brown – LSE / University of East Anglia

Stuart Brown – LSE / University of East Anglia

Stuart Brown is the Managing Editor of EUROPP. He is a Research Associate at the LSE’s Public Policy Group and a Senior Research Associate at the University of East Anglia.

“The left-leaning, largely Italian bilingual peninsula of Istria has always had a distinct identity and it remains the wealthiest region in Croatia” – was the intention here to say that Istra (why always use italianiazed form of Istria?) is predominantly ethnically Italian, or that Italian language is most widely spoken second language other than Croatian?

Also, Slavonia is not a northwestern region of Croatia, as it actual lies in the Eastern part of the country. That should be self-evident.

In other news, Most, Živi zid (Human wall rather that Human Blockade as you put it) and Orah will most likely steal some of the votes from both the SDP and HDZ, but due to wide ideological heterogeneity present in all the parties except for Orah, they are posed to face serious internal debate on the ideological front. This will make them a weak potential coalition party, regardless of what party they decide to side with, and will make any future government unstable as none of the two major parties are likely to win majority.

I think they will not be on the political scene for too long, although I do recognize the need for a viable alternative to the current bipolar party system.

Hi,

thanks for your comment and for pointing at the oversight about Slavonia – duly corrected.

‘Human Blockade’ is the translation to be found on Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_Blockade). We would have translated it as ‘Living Wall’, or indeed ‘Human Wall’ as you say but went for the most widespread use.

Again, ‘Istria’ (rather than ‘Istra’) is the standard English language spelling: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Istria

Bilingualism in Istria: we were of course referring to the fact that Italian is the most spoken second language.

Regards

Tena