On 3 December, Danish voters rejected a proposal from the government to change its status from being exempt from EU Justice and Home Affairs to a new position where it could ‘opt-in’ on legislation on a case-by-case basis. Sara Hagemann notes that the debate surrounding the referendum in Denmark was largely about ‘trust’ in the political system. Hence the ‘No’. Nevertheless, she stresses that the rejection is an ultimate dismissal of a Danish wish to participate in EU cooperation in an area which is set to define the Union in the future. It also comes at a politically sensitive time for the EU. Because of EU-sceptic pressures at home, other governments have to carefully consider whether to make Denmark a ‘case in point’, and decide what the consequences of an opt-out really are.

On 3 December, Danish voters rejected a proposal from the government to change its status from being exempt from EU Justice and Home Affairs to a new position where it could ‘opt-in’ on legislation on a case-by-case basis. Sara Hagemann notes that the debate surrounding the referendum in Denmark was largely about ‘trust’ in the political system. Hence the ‘No’. Nevertheless, she stresses that the rejection is an ultimate dismissal of a Danish wish to participate in EU cooperation in an area which is set to define the Union in the future. It also comes at a politically sensitive time for the EU. Because of EU-sceptic pressures at home, other governments have to carefully consider whether to make Denmark a ‘case in point’, and decide what the consequences of an opt-out really are.

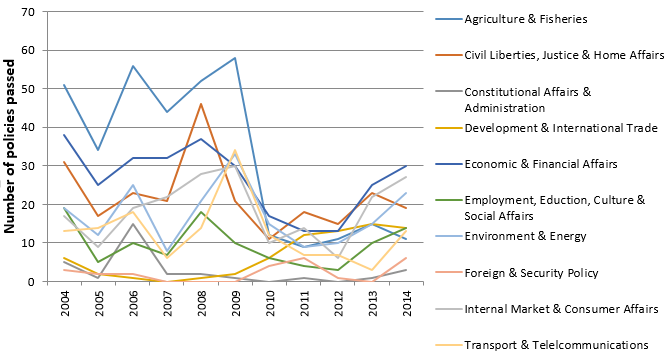

On Thursday 3rd December Denmark voted ‘No’ in a referendum on the question of whether to join its EU partners in the area of Justice and Home Affairs (JHA). JHA is of huge political importance as it covers issues such as asylum policies, police cooperation, border controls, data protection, bankruptcy rules, and much much more. It is also one of the areas with most policies passed by the governments at the EU level every year (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Policies adopted by the EU governments in the Council of the European Union per policy area (2004-2014)

Denmark has had an opt-out from this area since it first rejected the Maastricht treaty in a public vote in 1992. At the time, the Danish ‘No’ halted the ratification process for the whole Union, and the Danish government had to negotiate a set of opt-outs, which in addition to cooperation in justice and home affairs also include exceptions from the Euro and any EU common defence policies. The opt-outs meant that the government could return to the Danish public with a modified proposal of the Maastricht treaty in a second vote. That second vote resulted in a ‘Yes’ to the treaty, and hence allowed for the ratification process to continue.

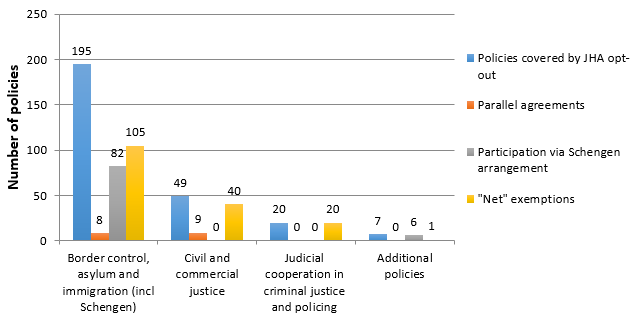

The rest of the EU could therefore move forward, and Denmark got a solution which took the pressure off the government domestically, and seemed to work for it in Brussels too: While not having the right to vote in areas within its opt-out, Denmark has been present in all JHA negotiations throughout the years, and has secured ‘parallel agreements’ with its EU partners on a number of occasions where it wished to apply important EU acts to Danish circumstances too.

It has also been able to transpose EU law directly into Danish law where policies were agreed at an intergovernmental level, allowing the Danish parliament to consider them as a version of international agreements rather than supranational policy-making by the EU institutions. (There are only three instances where the EU considered parallel agreements with Denmark not to be in their interest, and hence rejected a Danish request for participating in EU legislation).

In other words, Denmark’s opt-out has meant a status of ‘restricted member’ in negotiations, rather than an ‘outsider’. This is bound to change after last week’s vote.

Figure 2: Danish opt-outs and special arrangements in JHA

Snowball effect?

The ‘No’ last week did not draw headlines outside of Denmark to the same extent that it did in ’92, as there is no treaty or major political decision at stake for the rest of the EU member states this time. Indeed, there are no immediate changes for the remaining 27 members, and they may – at first – consider the rejection by the Danes rather ‘harmless’ at a time where the political agenda is busy enough as it is.

However, the consequences of the Danish ‘No’ could turn out to be considerable as EU leaders have to decide what to do with Denmark – should it be definitively excluded from all Justice and Home Affairs cooperation, including arrangements such as ‘parallel agreements’?

The main concern other EU governments have when making this decision is that they are themselves increasingly under pressure from EU sceptic parties and lobby groups at home. If the Danes have been able to sit in on JHA negotiations so far, and subsequently pick and choose between policies they did want to participate in, then why shouldn’t other countries be able to do the same? Allowing Denmark to continue in Europol, for instance, after an ultimate rejection of EU cooperation in such a defining area of EU affairs would send a signal that you can vote ‘No’, but still be able to get what you want.

That sort of fragmentation is detrimental not only to EU cooperation at a time where governments generally seek ways to cooperate more not less in order to address the many challenges in Europe today, such as those related to the refugee crisis, Eurozone governance, economic growth, and terrorism. But it is also a real challenge for governments’ own survival in a domestic political environment which has not been so polarised since WWII (the French regional elections offering a case in point).

Governments are hence aware that Denmark could set a precedent for any other countries that may seek to secure opt-outs or parallel deals in the future – whether within existing areas or under new initiatives (enhanced Eurozone or Schengen). And then there’s of course the dominant question of what deal the UK would get if it was to leave the Union. David Cameron will find the Danish dilemma particularly hard as it is in the UK’s interest to keep a door open on this question – but any ambiguity regarding the consequences of a ‘No’ would bolster the arguments of the leave campaign in the UK, and hence threaten the position of his own government.

EU leaders may therefore find it necessary to make Denmark a test case and show that there are real consequences of opting out of EU politics, whether partly or entirely.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1QgcShi

_________________________________

Sara Hagemann – LSE

Sara Hagemann – LSE

Sara Hagemann is Assistant Professor in European Politics at London School of Economics and Political Science and ESRC Senior Fellow in the UK in a Changing Europe programme (from January 2016).