Slovakia held parliamentary elections on 5 March. The ruling Smer-SD party, led by PM Robert Fico, won the largest share of support, but failed to secure a majority. Daniel Kral assesses the results, writing that the election has pushed Slovakia into uncharted waters, as a record eight parties managed to secure representation in parliament, leaving a fractured party system that will make stable governments difficult to form.

Slovakia held parliamentary elections on 5 March. The ruling Smer-SD party, led by PM Robert Fico, won the largest share of support, but failed to secure a majority. Daniel Kral assesses the results, writing that the election has pushed Slovakia into uncharted waters, as a record eight parties managed to secure representation in parliament, leaving a fractured party system that will make stable governments difficult to form.

The Slovak general election on 5 March resulted in a major political earthquake. With a turnout of almost 60 per cent – consistent with the few previous parliamentary elections that have taken place in the country – a record eight parties secured seats in the 150-strong parliament. Notably, a third of the vote was captured by new parties or parties previously outside parliament, including 8 per cent for the extreme far-right party ĽSNS, and 6.5 per cent for the three month old anti-establishment Sme Rodina (We Are a Family) party led by an extravagant businessman. For the first time in modern history, Slovakia faces the realistic prospect of political deadlock.

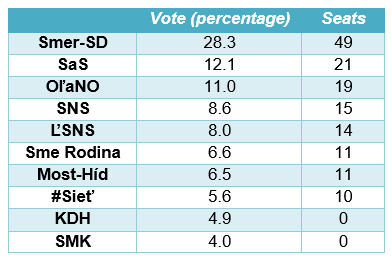

Table: Results of the 2016 Slovak parliamentary election

Note: For more information on the parties see: Smer-SD; Freedom and Solidarity (SaS); Ordinary People (OL’aNO); Slovak National Party (SNS); Kotleba – People’s Party Our Slovakia (L’SNS); We are a Family (Sme Rodina); Most–Híd; Network (#Siet‘); Christian Democratic Movement (KDH); Party of the Hungarian Community (SMK).

The incumbent Smer-SD, led by PM Robert Fico, won a bitter victory, losing 40 per cent of its MPs relative to 2012 and its majority in parliament. Smer’s poor showing, despite large welfare-handouts in the months before March, owes to three main factors. First, lacking a formal election programme two weeks before the election, Smer built the campaign uniquely on protecting Slovakia in the context of the migration crisis. However, since all parties spoke with one voice on the issue, Smer failed to differentiate itself from the competition and show its strength on other issues.

Second, Fico’s use of xenophobic rhetoric, such as promising to monitor all Muslims or to prevent the creation of a compact Muslim community in Slovakia, backfired. Trying to outcompete extremists on extremism, Fico wasn’t able to channel the anxiety he fuelled. Finally, a perfect storm struck Smer shortly before the election, with a general strike of teachers and mass walkouts of nurses demanding higher wages and pointing to the appalling state of Slovakia’s public services. Fico’s refusal to negotiate and his insistence that they have no reason to complain ran contrary to the everyday experiences of voters.

The economically libertarian Freedom and Solidarity (SaS) beat all expectations with its second place, largely owing to its sweeping victory in Bratislava – a traditional bastion of the centre-right. Judged as having the best economic programme by free-market think tanks, boasting experts on welfare, tax, healthcare or education reform, and with its leader, MEP Richard Sulík, voicing coherent views in fluent German in debates on German TV, the party successfully leveraged its expertise. Moreover, both SaS and the socially conservative but otherwise incoherent Ordinary People (OĽaNO), which came third, benefited from a clear rejection of any cooperation with Smer months before the vote.

Indeed, such outright rejection probably harmed the flavourless Christian Democrats (KDH) who for the first time since 1990 narrowly missed the 5 per cent threshold, losing voters to the much more energetic and vocal OĽaNO, and the #Sieť (Network) party of Radoslav Procházka, who had grand ambitions to lead a centre-right government, but barely entered parliament. Most-Híd, the centre-right leaning party representing the Hungarian minority shed two MPs relative to 2012, as it remained ambivalent about Smer and split the Hungarian vote with its competitor, SMK, which attracted 4 per cent.

Following four years in the political wilderness, the nationalist SNS ended in fourth place. No longer perceived as extremist, it probably has the best coalition potential. Indeed, SNS appears moderate compared to the biggest shock of the election, the breakthrough of the far-right ĽSNS, whose members glorify the war-time Slovak puppet Nazi state and, in some cases, deny the Holocaust. However, an exit poll revealed that its voters were overwhelmingly concerned with corruption and social issues. It is not widespread radicalisation, but desperation with mainstream parties which drove 8 per cent of the voters to embrace the extremists. Perhaps most worryingly, ĽSNS emerged as the most popular party among first time voters, just as its Hungarian counterpart, Jobbik, has been found most popular among Hungarian university students.

The success of the anti-establishment Sme Rodina party, which boasts conspiracy-espousing figures and organisers of the large but ineffective protests in the wake of the Gorilla scandal, further underscores the disenchantment of voters with established parties.

Possible scenarios

All parties that made it to parliament as well as the president, Andrej Kiska, who plays a largely ceremonial role in government formation, excluded any discussions with the far-right ĽSNS. Further complicating government formation is the reluctance of all centre-right parties, not just SaS and OĽaNO, to prop up a Smer-dominated government. Indeed, Smer needs the support of at least three of the smaller parties to secure a majority, which would be ideologically heterogeneous, conflictual, and most likely unstable. There is little appetite among all concerned to experiment with this alternative.

In a gesture of statesmanship, the unlikely new leader of the centre-right, Richard Sulík, vowed to lead a broad coalition that would exclude Smer, the extremist ĽSNS, and the anti-establishment Sme Rodina. There are obvious problems with this option. Relying on the slimmest majority possible, with 76 out of 150 MPs, serving a full term would likely be a Herculean task even in democracies where allegations of buying MPs to vote a certain way are not fresh in recent memory. Indeed, the previous attempt at a broad centre-right coalition after the 2010 general election lasted only 18 months. And to rely on tacit support of the unpredictable Sme Rodina would be a highly risky tactic.

The greatest hurdle for Sulík in the immediate term is to achieve a reconciliation of the nationalists with the Hungarians. While SNS hinted that it is willing to cooperate, Most-Híd faces a fundamental dilemma. Forming a government with the nationalist SNS may alienate its core Hungarian constituency, while being the stumbling block to a possible centre-right coalition may weaken its appeal among centre-right voters. In quickly excluding a coalition with Smer, Most-Híd made addressing this dilemma unavoidable.

It is possible that both Fico and Sulík will fail to forge a majority in parliament. Lacking a political culture allowing minority governments to rule over the longer-term, the president may appoint a caretaker government and call early elections within six months, which would overlap with Slovakia’s rotating presidency in the EU Council. No Czech governments since 2002 have served a full term, and Slovakia is perhaps becoming more Czech in terms of weak and unstable governments, even as the current Czech government looks set to finish its full term.

Implications

The election reflects Smer’s continued weakening on the back of a profound disillusionment with mainstream politics. The first big warning sign for Smer was Fico’s major defeat in the 2014 presidential run-off by Andrej Kiska, a non-partisan political underdog. In search of solutions to address perceived incompetence and widespread corruption – to a large extent nurtured by Smer during its eight years in power – a significant part of the electorate is desperate for quick fixes to Slovakia’s deep-rooted problems. Indeed, the retreat of the liberal pretense in Slovakia, just as in Hungary and Poland, has been primarily voter-driven.

Furthermore, as a result of the election, political discourse is no longer centred around the existence of a Smer and an anti-Smer bloc, but now includes a new dimension on containing the extremists. Ignoring the representatives of more than 200,000 voters who chose ĽSNS may fuel disillusionment not just with mainstream parties, but with the overall democratic process. It is crucial that the moderate parties study what worked and what didn’t in other European countries, for example in neighbouring Austria, whose far-right has traditionally had a much bigger presence in parliament.

Overall, the election spells the dawn of a new political era. In the first half of the 2000s, the dominant centre-right faced weak opposition, and was able to push through radical reforms that created big winners and losers. Riding the wave of reform fatigue while reaping the economic fruits of reform, Smer established its dominance, as the centre-right imploded. After the most recent election, the whole political scene looks fundamentally fractured. Indeed, weak, unstable or caretaker governments will hardly be able to decisively address the urgent concerns of the electorate, heralding possible further strengthening of the fringes, or the re-emergence of a strong Smer in the wake of chaos.

While many questions still remain and the dust is yet to settle, one thing is clear: Slovakia has entered uncharted waters.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1R77eQc

_________________________________

Daniel Kral – University College London

Daniel Kral – University College London

Daniel Kral is an alumnus of UCL’s School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES) and a forthcoming author who writes on East European politics and economics. He tweets @DanielKral1