Quantitative Easing (QE) – the unconventional form of monetary policy by which a central bank creates new money electronically to buy financial assets, thus helping to increase private sector spending and lower inflation – has been used by the European Central Bank (ECB) in the past. It is widely expected that an extension of the current QE programme will be announced during the ECB Governing Council meeting today, 10 March. What are the implications, and what are the risks? Eddie Gerba and Corrado Macchiarelli argue that the most effective way to deal with the root of the problem would be to accelerate the resolution of Non-Performing Loans (NPLs).

Quantitative Easing (QE) – the unconventional form of monetary policy by which a central bank creates new money electronically to buy financial assets, thus helping to increase private sector spending and lower inflation – has been used by the European Central Bank (ECB) in the past. It is widely expected that an extension of the current QE programme will be announced during the ECB Governing Council meeting today, 10 March. What are the implications, and what are the risks? Eddie Gerba and Corrado Macchiarelli argue that the most effective way to deal with the root of the problem would be to accelerate the resolution of Non-Performing Loans (NPLs).

There are high expectations that during today’s meeting (10 March 2016), the ECB’s Governing Council will extend its Quantitative Easing Programme. ECB chief Mario Draghi has in the past reiterated his readiness to adopt additional measures should the inflationary objectives not be reached by the upcoming meeting. With the Euro Area core inflation rate well below 1%, further monetary expansion now looks as the inevitable outcome. Different options are available, including the increase in the amount of monthly purchases of assets, currently set at €60 billion per month, but there are also significant risks involved, which we have recently outlined in a note to the European Parliament.

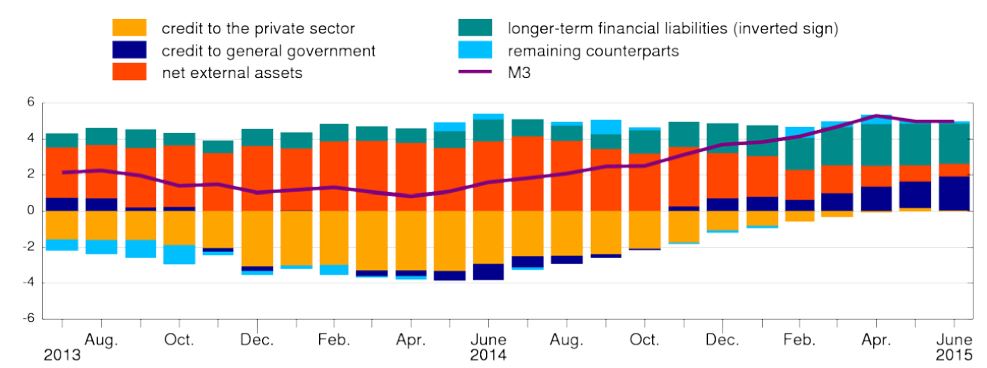

We evaluated the impact of the current QE framework on economic activity so far, in particular, bank lending. We observed a sharp downward trend. Even though bank lending in EA is slowly increasing, the level is still well below the level that would be needed to generate an improvement in the real activity. As shown in the figure below, the largest share of the growth in the money supply (M3) over the past year and a half is accounted for by an increase in credit to the public sector, and not credit to the private sector, which is the one required in order to generate economic growth.

Figure 1: Contribution of the M3 counterparts to the annual growth rate of M3 (percentage)

Source: European Central Bank, July 2015

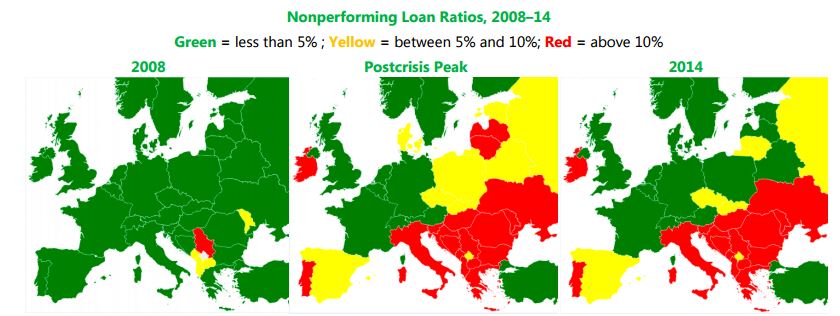

Since lending to the private sector has been pointed out as the key factor for reviving growth in Europe, the question remains to why the costs of borrowing remain high for firms and households. Recent studies by the IMF and BIS show that the reason behind the low levels of private sector lending is the vastly growing volume of non-performing loans (NPLs) across the continent. For the EU as a whole, NPLs stood at over 9 per cent of GDP at the end of 2014, or 1.3 trillion EUR. This is more than double the level recorded in 2009. The volume is especially high for the peripheral Eurozone countries, such as Portugal, Italy, Greece and Cyprus (Figure 2), and for small and medium-sized enterprises.

Figure 2: Non-performing loans in Europe

Source: Aiyar et al (2015) / International Monetary Fund

NPLs remain very persistent in the Euro Area, where the write-off rates for banks remain much lower than for US or Japanese banks. According to Aiyar et al., the reasons for that can be traced back to limited tax deductibility of provisions, weak debt enforcement and ineffective bankruptcy procedures that discourage write-offs and increase the cost of recovering assets provided as collateral for loans. Additional reasons are rigid accounting rules that hinder timely loss recognition and a lack of a sizeable market for distressed debt in Europe.

Likewise, a recent BIS study shows that the impact of monetary policy rate on bank profitability declines with the level of interest rates and the slope of the yield curve. The results of the paper imply that unusually low interest rates and an unusually flat term structure erode indeed bank profitability.

Bridging those two arguments, it means that the zero lower bound interest rate and QE, which intends to flatten the yield curve, risk increasing the volume of NPLs, eroding bank profitability even further, reducing credit-to-GDP ratios, and therefore putting at stake any opportunities for contemporaneous or future growth. This, however, would largely depend on the future stance and design of QE and any accompanying measures.

We conclude that the most effective way to deal with the root of this problem would be to accelerate NPL resolution, which would allow bank liquidity to be released. This could be achieved if:

- The ECB and national regulators tighten bank supervision;

- Structural reforms making bankruptcy more efficient and making it easier to collect debt are adopted;

- Markets for distressed assets are developed.

Other options of increasing the macroeconomic effectiveness of monetary expansion would consist in a joint monetary-fiscal stimulus, as well as direct lending of central banks to non-bank institutions or banks for a longer period of time (e.g. the so-called LTROs, long term refinancing operations providing cheap loan schemes for European banks).

Other possible options include extending the list of eligible collateral, increasing the pace of monthly purchases from the current 60 billion EUR, extending the deadline of QE beyond March 2017, or other similar twists to the current QE set-up. The latter measures, however, would not lead to a recovery of euro area economies – all they can do is to alleviate the current scarcity problem and buy time.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image: ECB head Mario Draghi (Wikimedia Commons). For further analysis and details, see the authors’ paper on the Monetary Dialogue website of the European Parliament.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1QLPDaX

_________________________________

Eddie Gerba – LSE

Eddie Gerba – LSE

Eddie Gerba is Research Fellow in Macroeconomics at the LSE European Institute.

Corrado Macchiarelli – Brunel University London and LSE

Corrado Macchiarelli – Brunel University London and LSE

Corrado Macchiarelli is lecturer at Brunel and a Visiting Fellow in European Political Economy at the LSE European Institute.