Spain’s anti-austerity party, Podemos, has announced that it will hold a grassroots referendum among its supporters to determine whether to back a proposed coalition led by the centre-left Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE). Should this last attempt to reach an agreement fail, it is expected that new elections will be held in the summer. Benito Cao writes on the key obstacles that have prevented a deal being reached until this point and assesses how new elections may play out for each of the main four parties.

Spain is going through one of its most turbulent political periods since the formal culmination of its democratic transition in 1978. Since then, with the only exception of the first elected government, the Spanish government has been in the hands of the centre-left Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) and the centre-right People’s Party (PP).

This two-party system has been shaken by the electoral success of two new national parties, the leftist Podemos (We Can) and the centrist Ciudadanos (Citizens). Both parties have capitalised on the discontent of a large sector of the Spanish population with the dominance of the PSOE and the PP – particularly the corruption that they are perceived to have allowed to flourish and from which they often profited. The calls for change increased during the protests of the so-called indignados (outraged) against austerity policies, culminating in the so called 15-M Movement, which began on 15 May 2011.

Since then, the big question has been to what extent that indignation would impact on the national political landscape. An answer was provided in the general election in December, where the vote produced a fragmented parliament, with four parties involved in political calculations to form government: the PP (with 29% of the vote and 123 seats), PSOE (22% of the vote and 90 seats), Podemos (21% of the vote and 69 seats), and Ciudadanos (14% of the vote and 40 seats). The remaining votes went mostly to regional parties, none of which has enough seats to facilitate the formation of a government.

Resolving the deadlock

The result left a complicated situation for all four parties, since none can govern without the support of at least one of the others. Moreover, in a parliament with 350 seats, neither the centre-right combination of PP + Ciudadanos (163 seats), nor the centre-left combination of PSOE + Podemos (159 seats) is enough to form a majority government. The only possible majorities are a grand coalition across ideological divisions including the PP and the PSOE, or a PSOE + Podemos coalition with the support of several leftist and regionalist parties. However, so far these options have been impossible to contemplate given the ‘red lines’ established by different parties.

Pedro Sánchez, the leader of the PSOE, has rejected any pact with the PP led by Mariano Rajoy. Moreover, the PSOE refuses to entertain a referendum on independence for Catalonia – a non-negotiable demand by several nationalist parties, and a significant section of Podemos. For their part, Pablo Iglesias, the leader of Podemos, refuses to enter into any government coalition with Ciudadanos, and Albert Rivera, the leader of Ciudadanos, rejects supporting any government that includes Podemos.

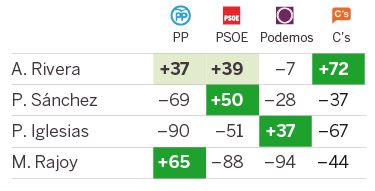

Figure: Approval ratings for the leaders of the four largest Spanish parties

[fusion_tabs layout=”horizontal” backgroundcolor=”” inactivecolor=””]

[fusion_tab title=”Net approval rating among all voters”]

[/fusion_tab]

[fusion_tab title=”Preference by party”]

[/fusion_tab]

[/fusion_tabs]

Note: Popularity of party leaders: net difference between voters (from all parties) who approve of the politician, and those who disapprove. Source: El Pais

The only possible negotiations which do not entail breaking established ‘red lines’ are between the PP and Ciudadanos, and between the PSOE and Ciudadanos. The first attempt to try to form a government was expected to be made by Rajoy, whose party, as he keeps reminding everyone, had the most support by a significant margin. However, when everyone expected him to seek a pact with Ciudadanos and submit himself to the investiture session, he refused to do so.

Rajoy argued that, given the PSOE’s rejection of a grand coalition, he did not have the required support to form a government. This refusal to submit himself to what would have been a barrage of criticism against his recent government was viewed at the time as a political masterstroke, one that shifted the focus onto Sánchez, who now had to face up to the task of succeeding where Rajoy had failed – or, more precisely, refused to fail.

Crucially, whilst Rajoy could afford the risk of going to a new election, Sánchez could not. Rajoy is largely in charge of his own future in the party, and the PP can expect the return of some voters from Ciudadanos. In contrast, the internal tension in the PSOE, with much of the old guard wishing to replace Sánchez, means that he had only one option: negotiate or perish. This was clear to Iglesias, who took advantage of that vulnerability to play hardball in his early engagement with Sánchez, and proposed conditions he knew Sánchez would not be able to accept, given his own ‘red lines’ and those of his party. This effectively left the leader of the PSOE with one card to play, negotiating with Ciudadanos. He did, and after a 200-point reform agreement, Sánchez presented his candidature for Prime Minister to Congress. He failed to get enough support in both investiture sessions – both times rejected by the PP and Podemos.

The unpredictability of how voters will respond if they have to return to the polls continues to keep everyone busy, and might tip the balance in favour of a last minute political compromise. However, the final result is hard to predict. The different parties are trying to read the mood of the people with every step of the negotiations. The main issue is that no one wants to be the first to cross a ‘red line’; but if no one does, Spain will have fresh elections in June.

Whilst the PP and Podemos initially appeared to be willing to go to another election, their political calculations have altered following the agreement between Sánchez and Rivera. Sánchez is now in a much stronger position to negotiate with Iglesias, who can no longer assume Podemos will profit from an early election at the expense of the PSOE. Iglesias has been forced to moderate his approach or risk an election that could severely punish Podemos. Indeed, a recent opinion poll indicates that Podemos would be replaced by Ciudadanos as the third most voted party. In the meantime, Rajoy continues to play his favourite game of waiting for others to fail and be ready to pounce when that happens.

How the whole saga will end remains to be seen; if no one is able to form a government by 2 May and Spain goes to another election, Sánchez’s ability to play the only card he had might just allow him to retain the PSOE’s leadership and get back some of the votes lost to Podemos. In that event, the 200-point agreement between Sánchez and Rivera could become the blueprint of the next Spanish government.

However, if the PP remains ahead of the PSOE and Ciudadanos displaces Podemos as the third political force, the next government will almost certainly be a coalition between the PP, with or without Rajoy, and Ciudadanos. Thus, whilst we are none the wiser as to the name of the next Spanish Prime Minister, there is one clear winner from the last two months of negotiations: Albert Rivera. In any case, and whatever the outcome of the current political deadlock, these are undeniably interesting political times in Spain.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Carlos Delgado (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/20y7F6y

_________________________________

Benito Cao – University of Adelaide

Benito Cao is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Adelaide.

Only problem with your article is to base it in a newspaper polls.

How you should know, in Spain, polls are highly biased for what party newspaper support.

Last elections has been a good example , with El Pais giving to Ciudadanos and Rivera results as large as two times what they got in real vote. AnywayEl Mundo, Abc or any other follow same line.

Your article would had been more accurate had you compared with what they published days before last elections.

Also, something is systematically ignored on Spanish media. Basques and Catalan parties have 25 seats. Enough votes to allow any combination of above mentioned parties -but PSOE+CC- to have a majority. A good insight would has been to analyze why none of Spanish ‘national’ parties wanted to negotiate with ‘national’ -not regional- Catalan or Basques parties.

I know polls are always biased, so I totally take that point. But, as a matter of fact, I had already written this article before that poll came out, with essentially the same line of argument, based on my understanding of Spanish political culture. When the poll came out, I thought it would make sense to add that to the piece since it was still time to do so. In any case, I don’t actually believe it is possible to predict with accuracy what will happen in the coming weeks -with or without polls. I am simply offering my interpretation of the situation, and I think Albert Rivera is the only clear winner from this period of negotiations. Whatever happens next, the status of Rivera and Ciudadanos has been greatly enhanced. There are still several possible outcomes, but after this period of negotiations I cannot see a single realistic outcome that does not include Rivera and Ciudadanos, with or without fresh elections.

I also take your point about calling Basque and Catalan nationalist parties ‘regional’ parties rather than ‘national’ parties. The problem is that when you have to write an article with limited space to explain all the nuances of Spanish politics, in English it makes more sense to call Basque and Catalan parties, regional parties, in the sense that they only present candidates in their regions rather than the whole of Spain. I don’t have a problem referring to the Basque Country and Catalunya, and Galicia (which is where I am from) as nations, but for the purposes of clarity (and brevity) I thought it best to use the expression ‘regional’ parties for those parties that do not compete for votes across the whole of Spain.

Your final comment is not quite correct. Podemos (one of the four national parties) is open to negotiations with Catalan and Basque nationalist parties, albeit only with those on the left (ERC and.Bildu). The reason why the other three national parties (PP, PSOE and Ciudadanos) are not open to such negotiations is simple: they categorically reject a referendum of independence, which has become a key demand in the recent elections, especially by the Catalan nationalist parties (ERC and Democràcia i Llibertat). This is one of the famous ‘red lines’ that neither the PP, the PSOE or Ciudadanos are willing to cross.

Thanks for your answer.

The only choice to form a government is PP+C´s with the Abstention of PSOE. The only problem is that PP has to accept the Citizen´s conditions that is:

1- Reach a agreement using the PSOE and Citizans pact as a base.

2- Rajoy renounce to lead the government (has to be new minister at the government especially young).

In the case, if there is new election according to the polls the results wont be necessary to PSOE to take part.

PP+C¨S with the support of CC and PNV. The PNV will be more favourable to open talks due to danger to lose his power in Basque country by the agreement of PODEMOS and BILDU that are twinned since a long time. According to the polls in Basque Country PP will be decisive in order to be PNV+PSOE government and avoid PODEMOS+BILDU at the power.

The danger is there. PNV will need PP in adition with PSOE. The case of Catalonia is different, The CDC and ERC are starting to break relation due to CDC is losing support election by election while ERC is growing.

1.- Are really PNV and CC able to reach a pact ? Some of ultra-centralist CC’s politics are not so much compatible with them. Would PNV accept a removal of Basque capability to set taxes ? would they accept removal of Diputaciones Forales (ts administrative division). It is not easy.

2.- Your comments about ERC and CDC. They are probably more a ‘wish’ on Madrid’s press than a real fact.

3,. Is actually feasible PP making Rajoy renounce before new elections ?. PP is a highly hierarchical party where all power is in a few hands on its top structure..

The cases of Basque administration divisions are different than the rest because its under constitutional protection so it will be impossible. There is not consitutional majority (70% of support in the parliament) to abolish them thats why they will renounce to demand it. The “cupo·” instead is very different that can be deal.

In PSOE -Citizens deal only affects to the “diputaciones de régimen común”.

Actually, is difficult to pressure Rajoy to resign because it needs PSOE for any agreement,and PSOE has rejected to any deal. In the future elections according to the Polls PSOE will be no necessary. Thats why for any aggrement PP will be forced to deal with Citizens and accept their demands.

PNV will be more favourable to reach an agreement (will reduce their demands) if their government is in danger.

My apologies if I am too rough. But to say ‘it is underconstitutional protections’ in Spain means absoluty nothing.

Only 2 examples related to both Catalonia and Basqye Country:

– For Article 2, both are not ‘Regions’ they are ‘Nationalities’

– For Artcile 3 both Basque and Catalan languages are official in their ‘Nationality’

After 38 year, has you ever seen any Law, Act or Administrive resolutions where any of both articles has been recognized to exists, developed or applied ?. Not.. Never. Actually it is how both articles had never existed.

If articles 2 and 3 never has been applied, who can say Basque Administration is protected because they have an Annex in the Constitution ?. They will have it until a majority on Spanish Palament does not decide to not apply it anymore.

And is there any party or parties with 2/3 of mp in the parliament who support the abolish of basque administration?. NO, obviously not.

Does they need to modify Spanish Constitution to not apply articles 2 or 3 ? Not.

Does they need to modify Spanish Constitution to not apply an Additional Provision (what you say it is a consitutional protection)? . A larger not.