What consequences will Britain’s EU referendum have for both the UK and the rest of Europe? In a series of papers published as a collaboration between EUROPP and CIDOB (the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs), LSE authors analyse the prospects for three scenarios – a Bremain, a ‘soft’ Brexit and a ‘harsh’ Brexit. Stuart Brown and Tena Prelec assess what would happen if the UK votes to remain. The full papers are available here.

What consequences will Britain’s EU referendum have for both the UK and the rest of Europe? In a series of papers published as a collaboration between EUROPP and CIDOB (the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs), LSE authors analyse the prospects for three scenarios – a Bremain, a ‘soft’ Brexit and a ‘harsh’ Brexit. Stuart Brown and Tena Prelec assess what would happen if the UK votes to remain. The full papers are available here.

A great deal of ink has already been spilled on the question of what a Brexit would mean for the UK and the rest of Europe. But the issue of what would happen if the UK were to vote to stay in the European Union has received far less attention in comparison. In some respects, this is understandable. While a Brexit would entail a radical reshaping of the UK’s relationship with Europe, and potentially have far reaching consequences for the nature of European politics in general, the implications of a ‘Bremain’ appear less momentous at first glance. But what would be the main implications for the UK and the EU should it opt to stay on 23 June?

Changes for the UK’s relationship with Europe

The first area in which there may be substantial changes following the referendum is the nature of the UK’s status within the European Union. The agreement secured by David Cameron in February had four key elements, broadly grouped around the themes of the Eurozone and economic governance, competitiveness, sovereignty, and free movement.

The deal has been sharply criticised by those on the leave side for failing to sufficiently reform the UK’s terms of membership, but other actors have noted the reforms contained within the agreement will nevertheless alter the UK’s status. Open Europe, for instance, state that while ‘the deal is not transformative’, it is not ‘trivial’ and amounts to ‘the largest single shift in a member state’s position within the EU’.

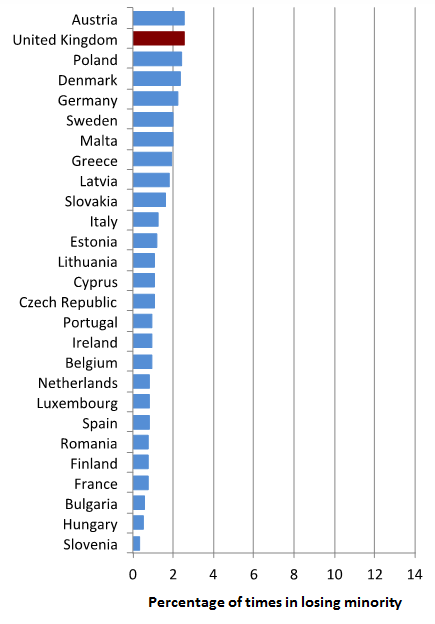

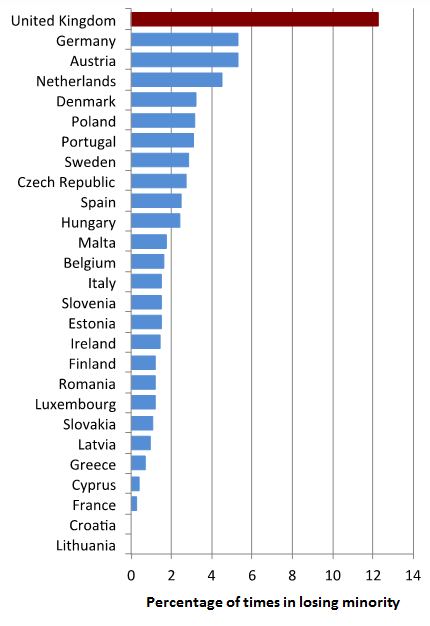

In some respects, the agreement has relevance beyond the substance of its reforms as it can be viewed as merely the latest development in a progressive hardening of the UK’s tone at the European level, over and above the specific details of the deal agreed. This trend can be traced at least as far back as 2010, when the Liberal Democrat and Conservative coalition first entered office. As Simon Hix and Sara Hagemann illustrate, the UK has shown far more willingness to lodge dissenting votes in the Council of the European Union since David Cameron came to power. Figure 1 below shows that while the UK was the second most likely state to formally cast a vote against a winning majority in the Council between 2004 and 2009, the percentage of times in which the UK has done so since 2009 has risen markedly to over 12% of votes.

Figure 1: Percentage of times EU states are in the losing minority in Council decisions (click to cycle through years)

[fusion_tabs layout=”horizontal” backgroundcolor=”” inactivecolor=””]

[fusion_tab title=”2004-2009″]

[/fusion_tab]

[fusion_tab title=”2009-2015″]

[/fusion_tab]

[/fusion_tabs]

Source: Hix and Hagemann

Of course, the nature of Council decision-making requires that these figures are placed in appropriate context. Council decisions are made in a climate of consensus, with many agreements not going to a formal vote. As such, the extent to which there has been a genuine shift in Britain’s EU policy since 2010 is debatable. It may be the case that the government simply wishes to signal its opposition to policies for the benefit of its domestic audience.

And it would hardly be surprising if the UK’s approach to EU policy issues at the European level changed in the aftermath of the referendum. The UK has long been one of the strongest supporters of enlargement, for instance, and has frequently expressed support for the accession of Western Balkan states and Turkey to the European Union. However, given the prospect of Turkish citizens being granted the right to move to the UK has been raised as a particular concern by leave campaigners, this position will be exceptionally problematic for the government to maintain.

Ultimately, the nature of the referendum result could have an impact on the extent to which the UK will continue to be regarded as an ‘awkward partner’ within the EU. A sizeable vote for remaining in the EU could, in theory at least, provide the British government with more of a mandate to take a leading role in European decision-making. Alternatively, a narrow vote to remain would likely tie the government’s hands further and raise unprecedented levels of scrutiny as to the UK’s involvement in future integration.

Changes within British domestic politics

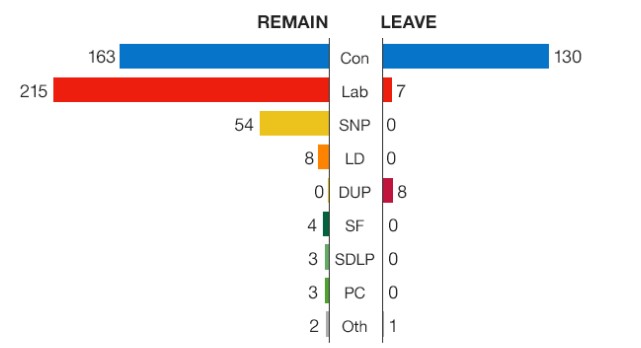

The UK’s referendum is of relevance not only for Britain’s relationship with the European Union, but also for domestic politics. The campaign is already having a profound effect on the discourses and policies of the main parties, most notably the Conservative Party, which is deeply split over the issue. Figure 2 below illustrates broadly how MPs split on the issue as of May.

Figure 2: Stances on the EU referendum as expressed by UK Members of Parliament

Note: The table records only the declared intentions of MPs, as of May 2016. Source: BBC

There are at least two major issues that the Conservatives would be obliged to face in the aftermath of a remain vote in the referendum. The first is how the party’s leadership should deal with the sizeable split that now exists among MPs. The second issue will be the prospect of a leadership contest before the next general election, with David Cameron already announcing his intention to step down before 2020.

Given the heated nature of the referendum, it is almost a certainty that this leadership contest will be dominated by the issue of Europe – and loose polls of some of the Conservative party membership, such as those carried out by the website Conservative Home, now show highly polarised positions toward pro-remain and pro-leave leadership candidates. Regardless of the result on 23 June, the Conservatives will be facing a period of political upheaval and it is difficult to determine how this will play out in the long-term.

Would UKIP emerge stronger from a remain vote?

One of the more interesting questions in terms of the effect a remain vote might have on the UK’s party system is the potential impact on UKIP. In the Scottish independence referendum in 2014, the relatively narrow win for the ‘No’ side was followed by an almost immediate spike in support for the pro-independence Scottish National Party (SNP), who subsequently won a record 56 (out of 59) Scottish seats in the 2015 UK general election. Some of the factors underpinning this electoral success were particular to the electoral situation within Scotland, but the notion that UKIP could experience a similar upturn in support following a remain vote in the EU referendum has nevertheless been the subject of some speculation among political commentators.

In practice, there are reasons to both support and reject this perspective. On the one hand, the referendum is creating a highly polarised atmosphere around the issue of Europe which UKIP, as the only major party with a united front in supporting a leave vote, would be well placed to capitalise on. This position would be made substantially stronger if the Conservative Party, following a victory in the referendum for David Cameron, declined to appoint an overtly Eurosceptic leader to lead the party into the next general election.

There are, however, also some important differences with regard to the Scottish example that may limit the potential for UKIP to experience a similar rise in support to the SNP. Even following a highly contentious referendum campaign, it is unlikely that the issue of Europe will retain the same degree of salience that independence held in Scotland following the 2014 referendum, where the entire party system has largely become polarised around the single issue of independence.

Moreover, there is a degree of division on the leave side which was entirely absent in the case of Scotland, given the split that currently exists between Vote Leave and Leave.EU/Grassroots Out. With this stated a close remain result would undoubtedly present a clear opportunity for UKIP to capitalise on popular feeling among those on the leave side.

The generation gap and a second referendum

A final aspect that is worth considering in relation to the effect of a remain vote on British domestic politics is the question of whether the referendum would genuinely settle the issue long-term. A substantial increase in support for UKIP could, as occurred in Scotland, raise the prospect of a second referendum – albeit this would actually be the third referendum held by the UK on Europe following the 1975 referendum. Indeed, Nigel Farage has been open about this possibility, noting that a narrow remain win could make it extremely difficult to avoid holding a further referendum on the topic.

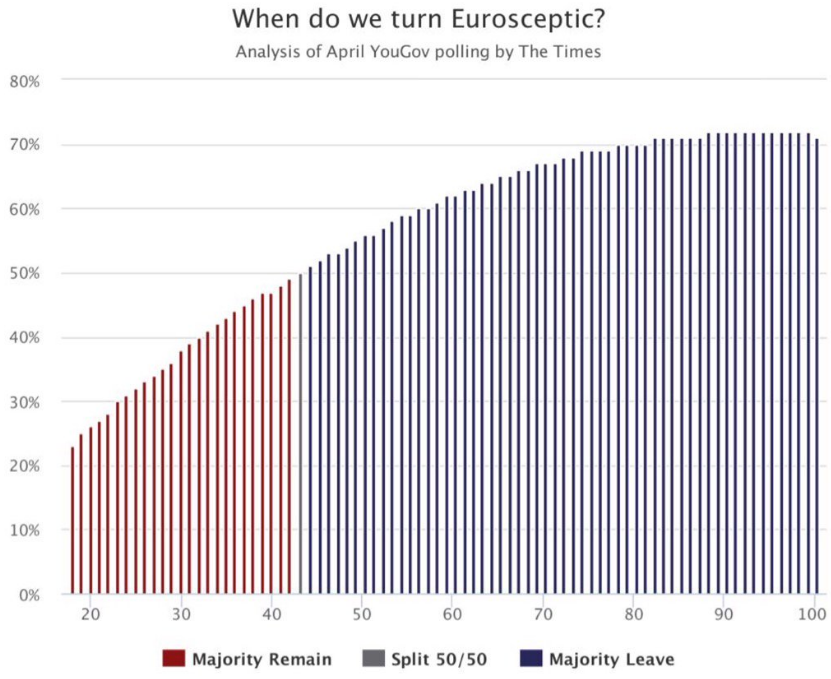

One aspect of relevance in this sense is the clear divide in views that exists within the UK between younger and older citizens. Polling by YouGov, illustrated in Figure 3 below, demonstrates a clear trend between the age of citizens and their opposition to the European Union, with older citizens far more likely to favour a vote to leave in the referendum.

Figure 3: Age and support for leaving the European Union (April 2016)

Research carried out by James Sloam suggests that the main factor underlying the distinctive stance taken by young voters is their prioritisation of key policy areas: young citizens are mostly concerned with ‘jobs, investment and the economy’ and display a much higher interest in the EU’s role in protecting human rights and fundamental freedoms than older voters. Only one in five voters in the 18-24 age bracket cite ‘Britain’s right to act independently’ as an issue of concern, compared to a third of all adults and almost half of those aged over 65.

Some of these priorities are likely to change with time: as citizens become older and acquire more stability in the labour market, the ‘creation of new jobs’ may become less of a concern. On the other hand, there is also a suggestion that the younger generation has had a more international upbringing, with more opportunities to connect with their peers and to travel across the continent (e.g. through the Erasmus programme). As such, it may be the case that support for the European Union will increase over time, reducing the demand for another referendum. Whether this age gap proves to be a lasting phenomenon that could impact on future referendums is therefore an open question.

Changes for the rest of Europe

While the UK’s referendum will have clear consequences in terms of the country’s relationship with Europe, it will also potentially have a lasting impact on the nature of the European Union itself.

The UK is far from the only country to have experienced a rise in Euroscepticism since the financial crisis and the referendum has been welcomed by other Eurosceptic parties across the continent. These include Marine Le Pen’s Front National in France, who have already published a plan for their own renegotiation and referendum; Geert Wilders’ Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV); the Italian Northern League (Lega Nord); and the Austrian Freedom Party.

What remains unclear is the effect a remain vote might have on these developments. Certainly, a British vote to leave the European Union might be expected to provide a substantial electoral boost to other Eurosceptic parties across Europe, but it is difficult to imagine that a decision to remain will take the heat out of the issue in other countries. The experience of Catalonia following the Scottish independence vote, for instance, suggests that a failed referendum can still act as a source of inspiration in other countries, with the debate becoming focused on the ‘right to decide’ in their own electoral contest.

Ultimately, the precise developments that would take place following a remain vote in the referendum will depend on a number of factors: the margin of victory, the effect on the leadership of the Conservative Party, the response from other parties in the UK, and the wider developments taking place in the rest of the EU. The one thing that does seem certain is that although the scale of the uncertainty that would accompany a remain vote is arguably of a lower magnitude than that associated with a Brexit, the referendum will set the agenda for not only the UK’s relationship with Europe, but also domestic British politics in the coming years. As such, both sides of the campaign are likely correct in their assertion that there is no genuine ‘status quo’ option on the ballot paper on 23 June.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image: Descrier / Flickr.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/24MTefB

_________________________________

Stuart Brown – LSE / University of East Anglia

Stuart Brown – LSE / University of East Anglia

Stuart Brown is a Research Associate at the London School of Economics, a Senior Research Associate at the University of East Anglia, and the Managing Editor of the London School of Economics’ EUROPP – European Politics and Policy blog. He is the author of The European Commission and Europe’s Democratic Process (Palgrave, 2016).

Tena Prelec – LSE / University of Sussex

Tena Prelec – LSE / University of Sussex

Tena Prelec is an ESRC-funded doctoral researcher at the School of Law, Politics and Sociology, University of Sussex, and Editor of the London School of Economics’ EUROPP – European Politics and Policy blog.