What is more in Westminster’s interest – to follow through the result of the referendum by leaving the EU, or to secure the survival of the United Kingdom? Jo Murkens continues his discussion on Britain’s constitutional arrangement arguing that the power-sharing with Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland since 1997 has changed the UK constitution, allowing space for each nation to see itself as politically autonomous. History shows that the Union can be preserved only by building bridges, not by burning them, he warns.

What is more in Westminster’s interest – to follow through the result of the referendum by leaving the EU, or to secure the survival of the United Kingdom? Jo Murkens continues his discussion on Britain’s constitutional arrangement arguing that the power-sharing with Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland since 1997 has changed the UK constitution, allowing space for each nation to see itself as politically autonomous. History shows that the Union can be preserved only by building bridges, not by burning them, he warns.

Can Parliament lead Britain out of the Brexit mess? At the first Prime Minister’s Questions after the referendum, PM David Cameron told parliament that ‘keeping the United Kingdom together is an absolute paramount national interest for our country’. Ironically, EU withdrawal cannot be said to be in the UK’s interest. The next prime minster would be well advised to pay special attention to the different outcome of the referendum in Scotland and Northern Ireland if he or she wishes to keep the UK together.

Constitutionally, the Westminster parliament is the sovereign law-maker of the United Kingdom. It is the sole institution empowered to repeal the European Communities Act 1972, which makes EU law binding in the UK. Parliament also maintains the authority to amend the devolution legislation for Scotland and Northern Ireland, which would be required in the event that the UK withdrew from the EU.

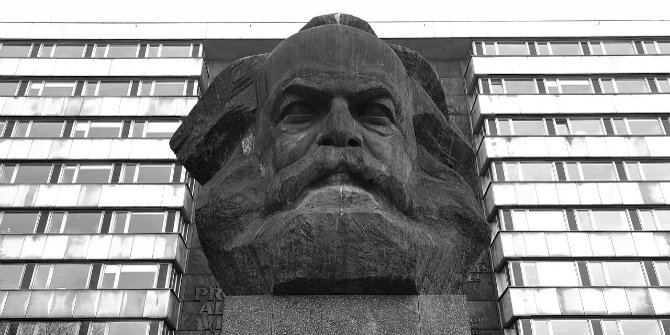

Westminster, London. Public domain.

Politically, however, the days where Westminster can legislate on behalf of Edinburgh and Belfast, and expect to get away with it, are over. The day after the result was announced Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness called for a border poll on a united Ireland. First Minister Nicola Sturgeon immediately talked up the prospect of a second referendum on Scottish Independence.

It is therefore incumbent upon the Members of Parliament to interpret the referendum result. MPs are not delegates who merely implement a decision made by others. If they were, they could not be held accountable for decisions made by parliament. Rather, MPs are representatives. They make decisions by weighing constituents’ views with the long-term good of the union as a whole. That exercise of political judgment explains why they are politically accountable. Before authorising the next prime minister to trigger Article 50, our MPs should be fully conscious that the future of the UK is at stake.

Strictly speaking, our MPs could even ignore the result of the referendum altogether. After all, they had the choice to make it either binding or non-binding. The 2011 UK-wide referendum on electoral reform, for example, contained an obligation on the government to legislate in the event of a ‘yes’ vote. No such provision was included in the EU referendum legislation. Parliament left it non-binding precisely to retain ultimate and independent legislative authority.

Parliament cannot so easily ignore the result, however, as a political matter. A better path would be for MPs to read the indeterminate referendum result in a different way.

MPs must recognise that the UK is split about withdrawal. A slight overall majority of people voted to leave (52-48), but that tally fails to reflect Britain’s established constitutional arrangements. First, the UK is a ‘family of nations’: two nations voted to leave, but two voted to stay. There is, therefore, an alternative argument to the dominant narrative that a majority of people voted to leave. Second, an argument based on ‘the will of the people’ cannot plausibly be invoked to renounce the constitutional doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty. Parliament is sovereign, and it must exercise its legislative power by considering the ambiguous referendum result as well as the long-term integrity of the UK.

We have been here before. In 1764, the British government imposed the Stamp Act (a new form of taxation) on the American colonies. It led to protests and unrest. Confusing the constitutional right to pass a law with the political wisdom to do so, the British government proceeded to make a bad situation worse.

The repeal of the Stamp Act was followed by the Declaratory Act 1766. It re-stated British sovereignty over America by asserting that parliament ‘had hath, and of right ought to have, full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to bind the colonies and people of America … in all cases whatsoever’. The rest, as we know, is history.

Richard Bourke argues compellingly that the British could have continued to include American membership of the Empire through some form of constitutional accommodation. Instead, he notes that ‘successive British governments stoked the mood of intransigence, animated by an overblown sense of imperial pride’. Instead of making political concessions, the government demonstrated its constitutional strength: ‘the more the metropole opted to display its might, the more it undermined its moral authority. Imperial militancy thus led to imperial impotence’.

What lessons can be drawn from history? The power-sharing arrangements with Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland since 1997 have changed the UK constitution. Legislative powers have been transferred from the Westminster Parliament to assemblies in Cardiff and Belfast, and the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh. Although the Westminster parliament retains the right to pass laws for any part of the UK, the reality is that those regions see themselves as politically autonomous.

In 1766 the priority of the British government was to secure the empire. In 2016, the priority for the next prime minister ought to be to secure the United Kingdom. Asserting the constitutional right of Westminster to withdraw Scotland and Northern Ireland from the EU ignores the reality that Westminster is no longer politically capable of enforcing that right. The more Westminster asserts its strength, the more it will lose its authority. The Union can only be kept together by building bridges, not by burning them across the English Channel.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article was originally posted on Open Democracy and it gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/29htKoK

_________________________________

Jo Murkens – LSE Law

Jo Murkens – LSE Law

Jo Murkens is Associate Professor in Law at the LSE. He was previously a researcher at the Constitution Unit, UCL, where he led the research on the legal, political and economic conditions and consequences of Scottish independence.

The result of the referendum is not ambiguous, the majority of the people voted to leave the EU.

To say that because the majority of people in certain geographical areas of the UK voted to remain makes leaving the EU unconstitutional is wishful thinking, not fact.

It was not THE majority of people, it was a majority of those who took part in the referendum. Those who are abstained from using their right to vote may well be mainly leavers, equally they main be remainers. Nobody knows. Thus to say the THE majority wish to leave is speculative at best, inaccurate by all accounts anyway and thus a minefield for parliament. They are on safe ground if they refuse to pass the necessary Act but insist on a new and better planned and informed referendum or simply say ‘No!’.

Absolutely spot on. We must be part of the bigger picture.

What a ridiculous heading. So by virtue of this heading the UK is already lost! 52% do not want to be part of the EU and so by definition if we remain then the UK is lost. For Christ’s sake grow up. I found no need to read the anymore than the heading as frankly this is simply a waste of everyones time.

I am always astonished by those who comment on something they have not read.

“I found no need to read any more than the heading as frankly this is simply a waste of everyone’s time” My word you must miss so much by believing that reading a headline means you know the whole story, Rupert Murdoch relies on people like you.

This article is an enlightening history lesson about the law in the country and I am grateful for it.

Clive, thank you for admitting that you didn’t even read the article. If only more people could be so honest while trolling.

OMG The ‘newly offended’ calling others trolls for expressing an opposing view. My god how childish.

The result of the EU Referendum was as follows :

To leave : 37.5%

To remain : 34.7%

No vote : 27.8%

So 62.5% of those entitled to vote expressed no desire to leave the EU.

65.3 % expressed the wish for the UK to leave the EU.

True there was a slight majority in favour of exit from EU. However. since it has been made crystal clear that the leave argument was built on a pack of lies. plus the fact that the unity of this Kingdom has to of paramount importance. I agree that parliament has to look at the bigger picture.

A very good article. I cannot believe the UK parliament has so far paid so little attention to the likely break up of the UK. I cannot imagine any other country in the world that would face the break up of its territorial integrity with the indifference that the UK parliament appears to be doing at present. This is indeed of paramount importance and should lead to Parliament vetoeing Brexit. Especially as it was both a 2-2 draw between the 4 UK nations and basically a draw also on the popular vote (52-48).

Technically there are 5 territories involved, not just four. England and Wales voted to leave, however Scotland, Northern Ireland and Gibraltar voted to remain.

I think we can rely, as in 1764, on any Tory government to automatically do the wrong thing (from it’s own point of view. The plain fact is that the UK is made up of constituent parts. Two (three?) of these parts, one of them overwhelmingly unanimously, voted to stay in the EU. For Scotland (and N.I. and Gibralter) to be removed from the EU against the popularly expressed will, would be a blow from which the UK would never recover. So the Union is doomed, no matter which course Westminster pursues. They can either make it clean and easy or dirty and prolonged. I am hoping for the former, but on past form, fearing the latter.

Scotland has 5 million people. Northern Ireland has under 2 million people. England has 55 million. It suits UK federalists to treat the 4 nations of the UK as equal – however, in a democracy where each person has one vote, England will always be far more important than the other 3 countries, even combined. This imbalance towards England is a price the 3 smaller nations pay to be part of the United Kingdom – and despite some complaining it appears one all 3 are willing to.

I live in Yorkshire, and we have more people than Scotland. If the country as a whole had been 52 Remain, 48 Leave, Yorkshire would still have been Leave. But there would be no legitimacy, in the eyes of this Leaver, for the English regions to demand we Leave the EU nonetheless if London and the Celtic nations had kept us in. Again: One person, one vote.

The author attempts to make out that the referendum result is not binding. Infact, constitutionally and politically, there is an unanswerable case that it is. The 2015 Conservative manifesto promised that the British people should decide on the question of EU membership ; the party was subsequently elected on that promise. Government ministers and other MPs, at the time the legislation passed through parliament, made clear the decision of UK voters in the referendum would be considered binding. The author also claims “Parliament is sovereign”; no, the British people are sovereign. Politicians are our servants, not our masters. Politicians refusing to implement the choice of the British people would be an unacceptable reversal of the way thins should be, provoking a constitutional crisis like this country has not seen. Thankfully it seems most MPs do not desire to overturn the result.

Even if your overriding concern is keeping the United Kingdom together, it is probably the case that Brexit makes such a brakeup less likely, though immediate post-vote analysis may suggest otherwise. True, in Northern Ireland there have been rumbles about a border poll, but there is no evidence there is widespread demand for one. The British and Irish PMs have made clear there will still be an open border in Ireland after Brexit. Yearly surveys show Nationalist sentiment in NI is declining, especially among Catholics.

Scotland (and, to a similiar extent, Wales) shows how Brexit makes the breakup of the UK less likely, especially in the long term. Remember, the SNP will do anything to further the cause of independence – and they advocated Remain in the referendum. Why? Because, while Brexit may indeed lead to a 2nd indy referendum, it is hardly the best case scenario for the SNP. Firsly, the deal on offer to Scotland – leaving a 300 year old union in order to join with Brussels, perhaps having to accept the Euro and austerity because of it’s budget deficit – is hardly attractive. It is hard to stir populist passion when Brussels is what you’re offering. Secondly, with Scotland’s oil sector now making a loss, the Scottish budget deficit is now the largest in Europe. Some in the SNP are saying independence

Over the long term, it will become less and less attractive for Scotland or Wales to jump out of the UK and back into the EU. This would mean leaving the UK internal market, far more important to both nations that the EU (infact, Scotland exports more to the rest of the world than the EU). It is likely that the British opt outs, for example the Euro, would no longer apply. It is also likely that feelings of Britishness will rise, while European identity will recede, further weakening Scottish / Welsh nationalism.

The problem for Scottish nationalists is that no one can conceive a scenario in which they could win a referendum. It’s true a majority in Scotland voted to remain in the EU on the very advantageous terms on offer to the UK, but if asked whether they would vote for independence on the basis of any terms Scotland may be offered by the EU a yes vote is doubtful. Leaving aside the oil revenue problems, the euro, Schengen and borders, would they willing pass from a Union which gives them 2 billion a year to one which invoices them for 3.5 billion?

@xerxes xu

I don’t think you can honestly cailm to make a like-for-like comparison here

essentially, you have 2 sets of circumstances

1) where Scotland (and Northern Ireland) are giving more legislative and fiscal autonomy within a federalised Britain dominated by England, they will still remain minnows/vassals of Westminster

irrespective of what the relationship between Britain and the EU will be, that’s essentially the current situation

whatever money that England disburse towards Scotland is first taken out of Scotland’s pocket

England may decide to top it up, but it comes at something else expense (no sovereignty, limited legislative autonomy …)

2) Scotland regains its sovereignty (that it gave up when signing the Act of Union), and notional full control over its legislative and fiscal powers

and decide to apply for EU membership

sure, it may lose grants from England (though it has to be negotiated re-cleaning of North Sea oil platforms, wind and hydro-electronic power generations, nuclear naval base leasing …), but it will have full decision over how to tax its citizens (more, less, whatever)

re-EU, that’s here things get more complicated in the details, so bear with me

a) euro

every member states “shall strive to meet the fundamentals for joining the European Common Currency”, bar Britain, Denmark and Sweden have opt-outs from joining the euro

the wording is important

it doesn’t say that you must adopt the euro as your new currency from day one or whatever your country fiscal/financial’s situation … no, you must earnestly try to follow the guidelines of good governance that would make you a candidate for the adoption of the euro AFTER you have joined the EU

the member country must first send its application to the ECB, then after monitoring for a period of time, it will send a proposal to the Commission and European Council for its refusal or a timetable for its acceptance

in short joining the EU doesn’t mean joining the euro, only practicing good governance such that in time you might be eligible to join the euro

and frankly, despite all the demonising made over the english pares, the euro, as a currency is quite a good one world-wise

better than sterling ? depending on what metrics you want to use, yes most certainly … and remember that we are talking about currency, not government macro-economic policy

b) Schengen

here is where it’s gonna be more problematic

Scotland may join the european common border agreement, but unless England accepts a EEA-like status with free movement of EU citizen, then a hard border for goods and people will be unavoidable between Scotland and England

because England wouldn’t want to let European citizens move freely into its territory through Scotland

and Europe will not let its markets be flooded with contraband, unsafe goods being shipped to England and carried over Scotland unchecked

and finally, sure, Scotland will have to contribute to the EU budget based on its GDP (rate is 1% for all members)

but if current flows persists, then Scotland is actually a net beneficiary of European funds (just like Northern Ireland) due to its agriculture, older population, and deindustrialisation following the Tatcher years

3) as for Northern Ireland, let’s just say that a convention to allow the progressive reunification of the island, like within a decade, would solve most of the constitutional issues raised by the referendum result