Croatia held a parliamentary election on 11 September, its second election in the space of a year following the country’s previous election in November 2015. Tena Prelec and Stuart Brown write that the results were a blow for Croatia’s Social Democrats, who had hoped to win the largest share of support but ended up in second place behind the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ). The elections have left a fragmented picture and may once again make it difficult for a stable governing coalition to emerge.

Croatia held a parliamentary election on 11 September, its second election in the space of a year following the country’s previous election in November 2015. Tena Prelec and Stuart Brown write that the results were a blow for Croatia’s Social Democrats, who had hoped to win the largest share of support but ended up in second place behind the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ). The elections have left a fragmented picture and may once again make it difficult for a stable governing coalition to emerge.

Contrary to expectations, Croatia’s Social Democrats (SDP) failed to win a majority of votes in the 11 September parliamentary contest. SDP leader Zoran Milanovic, who had previously served as PM from 2011 until the start of this year, led an increasingly confrontational campaign, heightening nationalistic and ‘anti-neighbourly’ rhetoric and pushing the party to the right. The hope was to gain more support from the centre ground, but the strategy backfired, with the party alienating its own electorate. Many former SDP voters appear to have turned their backs on the SDP by casting their preference for one of the minor parties or by not turning up at polling stations: turnout was significantly lower (by 8 percent) than at the last elections in November 2015.

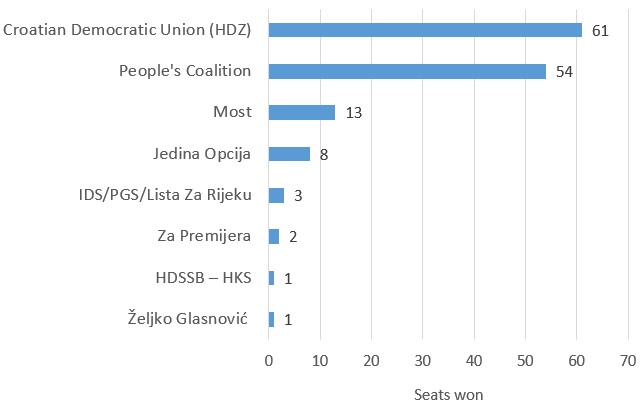

The best result was achieved by the most sizeable right-wing party, the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ). Unlike the SDP – which led the so called ‘People’s Coalition’ that also included the Croatian People’s Party – Liberal Democrats (HNS), Croatian Peasant Party (HSS) and Croatian Party of Pensioners (HSU) – the HDZ ran on its own this time, securing 61 mandates as opposed to the left-leaning coalition’s 54.

Figure: Seats won at the 2016 Croatian parliamentary election

Note: Figures from nacional.hr. For more information on the parties, see Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ); People’s Coalition (led by the Social Democratic Party of Croatia – SDP); Jedina Opcija Coalition (including Živi zid – ŽZ); Bridge of Independent Lists (Most); IDS/PGS/Lista Za Rijeku (see Istrian Democratic Assembly – IDS); Za Premijera (led by Milan Bandic); HDSSB – HKS.

The result is even more striking considering that the HDZ had been discredited by a recent scandal involving their former party leader, Tomislav Karamarko. In a series of events which triggered the end of the fragile and short-lived Orešković government, Karamarko had to resign in June this year after the weekly magazine Nacional revealed that his wife had received €60,000 to counsel a lobbyist for the Hungarian firm MOL, which has a strong presence in the national energy company INA. This is not the first time that the HDZ has been involved in corruption scandals: the most high-profile one involved former PM Ivo Sanader, who was accused of receiving ten million euros in bribes during the earlier stages of the INA-MOL deal.

The new HDZ party leader Andrej Plenković arguably succeeded in the arduous task of giving a new face to the party in the space of just a few months. Plenković, a former lawyer and diplomat who is currently still a Member of the European Parliament, has been characterised as someone who does not fit with the (traditionally nationalist) image of the party. He has avoided inflaming the debate to a large extent, but has also failed to sideline some of the most controversial personalities within the HDZ, such as the Minister of Culture Zlatko Hasanbegović (who is accused of being an Ustaša apologist). This difference in style was the only real differentiation in the two main contenders’ campaigns, which were fought on broadly similar programmes.

The third strongest contender, Most Nezavisnih Lista (Bridge of Independent Lists), obtained 13 seats – down from 19 in November 2015, while the coalition Jedina Opcija (Only Choice) led by the anti-establishment party Zivi Zid (Living Wall), made a strong showing collecting eight seats. The regional party IDS in Istria confirmed their presence in the territory by obtaining three seats; the populist mayor of Zagreb, Milan Bandić, obtained two seats; while the Croatian Democratic Alliance of Slavonia and Baranja (HDSSB) and the independent candidate Željko Glasnović obtained one seat each. The high number of votes cast for newly-established minor parties has been a recurring phenomenon in recent years, going back to the European Parliament elections in 2014, where the environmental party ORaH came third with nearly 10 percent of the vote.

Many Croatian voters are clearly looking for an alternative to the binary option they have been presented with until recently, but as yet they have still to find a party that can seriously challenge the HDZ and SDP for power. The outcome is an increasingly fragmented party system which will once again present major challenges for the formation of a stable government capable of pushing through the reforms the country urgently needs. The economy has only recently shown some timid growth after six years of stagnation, but much of this growth has been attributed to tourism along the country’s Adriatic coast and unemployment remains at very high levels.

For now, Plenković has excluded the possibility of a grand coalition and wants to lead the negotiations for the formation of the government. MOST has already set out a list of requirements for its participation in government and negotiations are once again likely to be a fraught affair. A ‘Spanish scenario’ might however be avoided: after initially hinting at the need for a stable government – and therefore potentially to a grand coalition – Milanović has announced that he will not be standing in the next elections for the party leadership. By doing so, he has also implicitly conceded victory to the HDZ, though he refuses to extend his congratulations to Plenković before the latter apologises for remarks which were made during the campaign.

It is an open question, however, how stable a new HDZ-led government will be, as any coalition options will lead to only a slim majority in parliament. The only point everyone concurs on is that the disengagement of Croatian voters, evident in the low turnout, is an alarm bell pointing at deep disaffection in the way politics is currently conducted in the country.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image: HDZ leader Andrej Plenković, credits Comite des Regions (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2cGUTAr

_________________________________

About the authors

Tena Prelec – LSE / University of Sussex

Tena Prelec is an Editor of EUROPP. She is a doctoral researcher at the University of Sussex and keeps an active involvement in the LSE’s research unit on South Eastern Europe, LSEE.

Stuart Brown – LSE

Stuart Brown is the Managing Editor of EUROPP and a Research Associate at the LSE’s Public Policy Group. He recently published a book on the European Commission, The European Commission and Europe’s Democratic Process (Palgrave, 2016).