The province of South Tyrol experienced violent unrest in the post-war period, before being granted autonomous status within Italy in 1972. As Stephen J. Larin and Marc Röggla note, the province is currently debating the revision of its 1972 agreement by holding an ‘Autonomy Convention’. They argue that although the ability of citizens to participate in this process has been more limited than originally envisaged, the convention is nevertheless evidence of the potential for power-sharing models to transform conflicts and ease tensions in disputed territories.

The province of South Tyrol experienced violent unrest in the post-war period, before being granted autonomous status within Italy in 1972. As Stephen J. Larin and Marc Röggla note, the province is currently debating the revision of its 1972 agreement by holding an ‘Autonomy Convention’. They argue that although the ability of citizens to participate in this process has been more limited than originally envisaged, the convention is nevertheless evidence of the potential for power-sharing models to transform conflicts and ease tensions in disputed territories.

South Tyrol, the northern-most and predominantly German-speaking province of Italy, is one of the most successful cases of consociational conflict regulation in the world. From 1972, the province has enjoyed autonomous status within Italy, following a period of unrest dating back to the 1950s. However, in January this year, the province began an ‘Autonomy Convention’, billed by the Provincial Council as a participatory democratic process to debate and draft a proposal for revising the 1972 Autonomy Statute, in the context of Italy’s current discussions around constitutional reform.

Does this process represent a new type of consociational negotiation, which is normally elitist by design? The preliminary answer is ‘no’, and the Convention, which returned last month from a summer break, seems unlikely to fully succeed on its own terms. But the problems that it faces, and the fact that it has occurred at all, may be evidence of consociational democracy’s potential to transform conflicts. The Convention is the result of ‘normal’, not ‘ethnic’ politics, and power-sharing made that possible.

South Tyrol and its autonomy arrangement

South Tyrol was part of the Austro–Hungarian Empire until it was annexed by Italy at the end of the First World War. The Fascists subjected the province to a campaign of forced Italianisation through the repression of the German language, mass migration of Italian-speakers to the province, and resettlement of the German-speaking population to the Third Reich.

Official assimilation ended after the Second World War, but the dominance of Italian-speakers continued. The 1946 ‘Gruber–Degaspari Agreement’ between Austria and Italy was supposed to protect German-speakers, but a 1948 Autonomy Statute did not implement the agreement properly. Italian was still the dominant language of the public service, the state continued to assist southern Italians to migrate to South Tyrol, and as a minority in the two-province ‘Autonomous Region of Trentino–Alto Adige’, the German-speakers were regularly outvoted on issues that affected them as a group.

This led the South Tyrolean People’s Party (Südtiroler Volkspartei, SVP) to begin agitating for greater provincial autonomy in the mid-1950s, and Austria brought the issue to the United Nations General Assembly in the early 1960s. Throughout the 1960s, German-speaking militants carried out a series of sometimes deadly bomb attacks against symbols of Italian state authority, resulting in mass arrests and allegations of torture.

In 1964 an inter-language-group state commission produced a report on how to revise the Autonomy Statute that served as the basis for a reform package the SVP accepted by a narrow margin in 1969. The so-called ‘Second’ Autonomy Statute, which entered into force in 1972, devolved most powers from the Region to the Provinces and instituted consociationalism in South Tyrol, including measures such as reserved positions, executive and public service proportionality, cultural autonomy, a ‘group right to challenge’ (often misrepresented as a veto), and mandatory bilingualism for all public service employees.

The Statute took twenty years to implement, but Austria declared the conflict settled in 1992, and relations between the province’s three official language groups (69.4 per cent German, 26.1 per cent Italian, and 4.5 per cent Ladin-speakers in 2011) have continued to improve.

The Autonomy Convention

It is widely acknowledged that the Autonomy Statute needs to be updated to reflect the many enactment decrees and other developments that have taken place since 1972 which have amended the Statute in practice. It is also viewed as necessary to respond in some way to successive Italian governments’ push to recentralise the state.

The basic idea for the Autonomy Convention began with now-President Arno Kompatscher’s run to lead the SVP, as a way to legitimate the amendment process. In 2013 it was incorporated as a minor point in the party’s election platform and then ‘Coalition Programme’ with its Democratic Party (Partito Democratico Alto Adige, PD) partner. It gained new significance in 2014 when Matteo Renzi initiated constitutional reforms that are intended to be put to referendum later this year (see Codogno for an argument in favour of the referendum proposition, and Pasquino and Capussela against it).

In April 2015, South Tyrol’s Provincial Council adopted a law to create a ‘South Tyrol Autonomy Convention’. It passed by 18 votes to 17, with all seven German-language, Italian-language, and inter-group opposition parties voting against it. The government is not open to suggestions for improvement, they argued, and the supposedly ‘participatory’ process was already tainted by elitism.

The Autonomy Convention began in January nonetheless, and is scheduled to continue until April 2017, with the option of a six-month extension if necessary. It has three main components: ‘Open Spaces’, the ‘Forum of 100’, and the ‘Convention of 33’. Nine ‘Open Space’ discussion events were held across South Tyrol from 23 January to 5 March. The main objective of these meetings was to give all members of the public the opportunity to speak their mind and offer suggestions on how to revise the Autonomy Statute. In total, around 2,000 people participated in 258 discussions.

The participants differed demographically and politically across venues, but in general Italian-speakers, women, and young adults were under-represented. A wide range of topics were discussed, such as proportionality, the separate school systems that currently exist, place names, immigration, and self-determination. The event held in the Ladin-speaking area focused on issues important to that group, such as guaranteed representation on the Provincial executive. Summary reports of every discussion are available on the Convention’s website.

One group, the ‘patriotic association’ known as the Schützen, carefully coordinated its members’ participation. This significantly affected the character of the events, and encouraged the public perception that the Open Spaces mainly provided a stage for right-wing German-speaking nationalists.

The ‘Forum of 100’ and the ‘Convention of 33’ are each a kind of citizens’ assembly, and their membership is proportionate to the distribution of the three official language groups, gender, and age in the province’s population. The Forum is composed of volunteers selected through a group-segmented lottery. Its main purpose is to deliberate on the Statute and offer suggestions for change to the Convention of 33, the Autonomy Convention’s real decision-making body, which is appointed by the Provincial Council following a ‘corporatist’ model that represents a variety of political and civil society interests.

The Forum has only met three times since April, but is the site of two of the Convention’s major controversies. First, the SVP was accused of registering its members for the Forum without their consent or even knowledge. The SVP denied any wrongdoing, saying that it only wanted to assist its members with online registration, but the main opposition party still lodged a complaint with the local prosecutor’s office. Second, the selection of the eight Forum representatives to the Convention of 33 was widely criticised because the vote was not segregated by language group. All members of the Forum voted on all of the representatives, which critics said gave the German majority control and undermined Italian-language representatives who are not perceived to be ‘really Italian’.

The Convention of 33 also first met in April, and will meet at least twice monthly until the end of the process. So far, it has decided on and begun discussing the five main themes of its deliberation, based in part on issues raised in the Open Spaces: the role and future of the Region; minority protection; the Province’s legislative powers; self-determination; and the relationship between South Tyrol, the European Union, and the European Region Tyrol–South Tyrol–Trentino. It has struggled to find its footing, however, and Luis Durnwalder, the former long-time President of South Tyrol and now one of the government’s representatives in the Convention, has used it as a personal political platform.

Participatory consociationalism? No, but…

On paper, the Autonomy Convention looks like a world-first attempt to use a participatory democratic process to renegotiate a consociational power-sharing arrangement. In reality, it is only a ‘participatory-ish’ consultation.

The Open Spaces and the Forum of 100 are genuine exercises in participation, but they can only make suggestions. The Convention of 33, which is mostly made up of politicians and interest groups, will decide what the proposal looks like. Nothing that the Convention produces is legally binding, though, so it is even possible that the Provincial Council will simply ignore whatever is proposed. And in the meantime, politicians have continued to negotiate Provincial competencies with Rome.

The Autonomy Convention is therefore best understood as a political strategy to legitimise a fundamentally elite-driven amendment process. And given the problems that the process has faced, this strategy seems to be less effective than the government had anticipated. Whatever the Convention’s outcome will be, however, we believe that both the fact and the circumstances of its occurrence are significant.

An outside expert on divided territories might expect that the Convention was precipitated by a negative change in the relationship between South Tyrol’s three official language groups that requires the Autonomy Statute to be amended. This is not the case. Both the Autonomy Convention and its challenges are the result of ‘normal’ rather than ‘ethnic’ politics. South Tyrol is still socially and spatially segregated, but the Convention was conceived and implemented by a faction of the SVP, along with the PD, as a small part of a strategy to reposition the parties within provincial politics and address the constitutional reform process. Nothing more.

It is also important to understand that even a ‘participatory-ish’ process like this would have been impossible in the 1960s, and still difficult to imagine as late as 20 years ago. Now, however, two generations after the Second Autonomy Statute, none of the three official language groups sees the mere prospect of the Statute’s amendment as an inherent threat to their security, and no one is afraid to talk about it.

Few Italian-speakers participated in the Open Spaces, but even if they rejected the Convention process, we would expect to see some kind of protest if it were perceived to threaten their group. Many people are unsatisfied with how the Convention has played out, and some blame its problems on the nationalist fringe, but nobody could credibly blame ‘ethnic conflict’ if it fails.

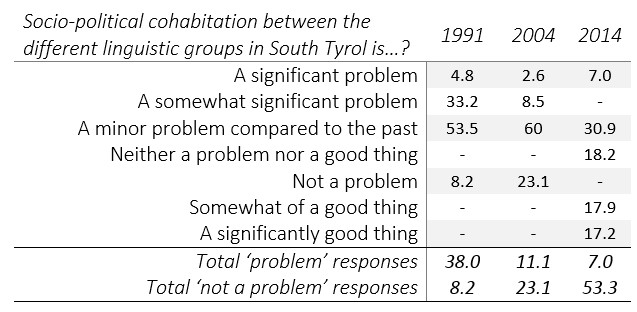

There is a clear and striking progression in attitudes about ‘socio-political cohabitation’ between the three official language groups in surveys performed by the Province’s statistical institute (ASTAT) from 1991 – one year before Austria declared the Autonomy Statute fully implemented – 2004, and 2014, summarised in the table below.

Table: Views on ‘socio-political cohabitation’ in South Tyrol (1991-2014)

Note: The 2014 survey used a different set of possible answers. Dashes (‘-’) indicate that an answer was not part of the survey in the given year. The authors have added the totals to help clarify the trend across surveys. Don’t know responses have been removed from the results.

Furthermore, a significant majority of those surveyed (71 per cent in 2004 and 73.6 per cent in 2014) said that they expect the relationship to either stay the same or improve in the future. Günther Pallaver has also provided more evidence of changing attitudes which is available here.

Several factors have contributed to this progress, but the most important is consociational power-sharing, which has transformed the conflict by desecuritising the relationship between each of the language groups in South Tyrol. It is, we think, an example of what John McGarry calls the ‘consociational paradox’: that institutional accommodation of rival groups and an extensive period of cooperation between them can transform the relationship over the long, multi-generational term. This is the silver lining on the clouds over South Tyrol’s Autonomy Convention.

For more information on South Tyrol’s history and autonomy arrangement in English, see the Autonomy Arrangements in the World website, The South Tyrol Question, and Tolerance Through Law. A comprehensive bibliography of English-language literature on South Tyrol is available here.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics or EURAC. Featured image: CC0 Public Domain.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2emM4Rr

_________________________________

Stephen J. Larin – EURAC

Stephen J. Larin – EURAC

Stephen J. Larin (@sjlarin) is a political scientist and Senior Researcher with the Institute for Minority Rights at the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano (EURAC), Italy. His research focuses on the relationship between majority nationalism and minorities such as migrants and sub-state nations. He is co-editor with Bruce J. Berman and André Laliberté of The Moral Economies of Ethnic and Nationalist Claims (UBC Press, 2016), co-editor with Per Mouritsen of “The Civic Turn in European Immigrant Integration Policies”, a special journal issue accepted by the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, and editor of The Politics and Law of Plurinational States: Contemporary Developments, which will be published by Peter Lang as part of its ‘Diversitas’ series.

Marc Röggla – EURAC

Marc Röggla – EURAC

Marc Röggla (@MRggla) is a trained lawyer and Researcher with the Institute for Minority Rights at the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano (EURAC), Italy. His research focuses on minority autonomy, protection, and media. He is one of two coordinators of EURAC’s administrative and advisory role in South Tyrol’s Autonomy Convention, and a EURAC representative in the European Association of Newspapers in Minority and Regional Languages (MIDAS).