Only a year ago, Romania’s Social Democratic Party (PSD) were in deep trouble over corruption allegations, whose magnitude was exposed after a deadly incident in a Bucharest night club. How did the PSD, then, end up winning the 11 December parliamentary elections? Mihnea Stoica explains that the hesitation showed by the technocratic PM Dacian Cioloș to shake up the country’s administrative system has negatively impacted on the National Liberal Party (PNL) that supports him, thus contributing to the PSD’s comeback.

The Romanian parliamentary elections held on 11 December produced a landslide result for the country’s social democrats (PSD), with a magnitude of victory that was unimaginable less than a year ago. In November 2015, former socialist Prime Minister Victor Ponta resigned due to pressure from street protests that linked high corruption levels to a tragedy in a nightclub which claimed the lives of more than 60 people. The Parliament in Bucharest subsequently established a ‘technocratic’ government – a cabinet that, in theory at least, was formed of politically independent specialists. The government had the aim of taking bold measures to move toward an efficient administration on the one side and to promote progressive social policies on the other.

The situation seemed to favour the National Liberal Party (PNL), which was strongly associated with the new government and which therefore hoped to capitalise on popular enthusiasm for a clean slate that the new ministers were expected to bring along – most of them having had little or no direct connection with party politics before entering office. The PSD was in a particularly delicate situation, for both having lost its government positions and for being depicted as solely responsible for the high levels of corruption in the country which the new government was now expected to eradicate.

In practice, the new cabinet led by former European Commissioner Dacian Cioloș proved to be quite hesitant in shaking up the country’s administrative system – the same system criticised for its high corruption rates. Moreover, the non-political dimension of the technocrat government appeared to be little more than a façade which started showing some serious cracks, especially when several initially independent ministers defected to Union Save Romania (USR) – a newly created political party with an unclear ideological orientation, approximating a catch-all anti-establishment party.

Soon enough, the reflex of political conservation took over. Now, every mistake by the Prime Minister was made at the expense of the PNL, who openly backed Cioloș. And this was not the only troubling reality for the right-wing liberals, as they were facing strong competition from USR. The latter attracted much of the support of dissatisfied young voters, who felt uneasy with voting for either of the two major parties of the establishment, but who would have rather voted for the PNL in the absence of an alternative.

When it came to the 2016 elections, the campaign of the PSD focused much more on the party’s electoral programme, while the campaign run by the PNL was very much personalised around the image of Dacian Cioloș. It was a poorly conceived approach, especially given several changes in the electoral system which shifted to a proportional system that favours parties over faces.

This only amplified the void of debates on matters truly affecting the future of the country. Few public figures have drawn attention to substantive issues, although Deputy Prime-Minister Vasile Dîncu and EU Commissioner Corina Crețu are exceptions to this rule (but were not standing for any elected position in the elections). Therefore, paradoxically, the sources of debate were located outside of the electoral campaign itself.

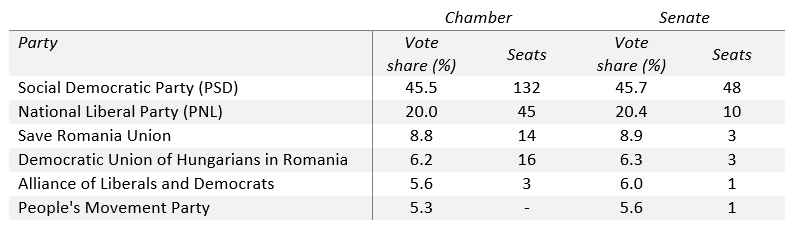

Table 1: Partial result of the 2016 Romanian parliamentary election

Note: These figures are partial results and will be updated. Only parties with seats in parliament are shown.

The final results matched what most opinion polls had predicted. The PNL suffered a second political backlash over austerity measures that had been implemented by the Romanian government prior to the 2012 election (the PDL, which participated in this government, merged into the PNL in 2014). The first backlash was in the 2012 election when the PDL was reduced to almost half its size, but the impact of this was softened by the surprise victory of liberal candidate Klaus Iohannis in the 2014 presidential elections.

In the 2016 elections, the PNL decided to primarily bet on candidates who had been successful back in the heyday of the right in the early to mid-2000s, when the left were forced into opposition. These now ageing liberal candidates created the opposite image of the social democrats, who included on their lists many young people with few connections to the much-condemned political system, far less the former Communist regime. The classic discourse of the right in Romania, which pits ‘Communists vs Democrats’, simply no longer worked in 2016.

But the result of the election is more complex than it appears at first glance. The United Romania Party (PRU), a newly created nationalist populist party (in fact a splinter of the social democrats) was prevented from entering Parliament as its share of the votes did not surpass the 5% threshold. However, this does not mean that the anti-establishment discourse was left without followers. On the contrary, such messages are stronger than ever, even if they emerge from two opposing perspectives. On the one hand, conservative politicians portray the activity of anti-corruption institutions as a dangerous development that should be tempered, while among progressive politicians, mainstream attitudes on issues such as minority rights are a common target.

Therefore, the ideological boundaries that these elections will prove to have highlighted are not so much between parties as they are within them. On the economic axis, the preference of the electorate for left-leaning policies is now a certainty. But if the economic questions have received a clear-cut answer, the exponential increase of the number of left-wing MPs will further develop the ideological debate on the progressive-conservative axis.

The following four years might not provide coherent answers, but these issues will certainly weigh more than they did before. Meanwhile, the PNL is expected to start a painful process of reinventing its political identity. The government’s performance in the next two and a half years before the next elections (which will be those for the European Parliament) are crucial for the fate of the PSD, whose main challenge is now to secure loyalty from its large body of supporters.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: PSD (CC BY SA).

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2gVNvCK

_________________________________

Mihnea Stoica – Babes-Bolyai University

Mihnea Stoica – Babes-Bolyai University

Mihnea Stoica, PhD is a research assistant at the Babes-Bolyai University in Cluj-Napoca, Romania. He holds an MSc in Comparative European Politics from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and has worked as an MEP adviser at the European Parliament. His research interests revolve around political communication, focusing mainly on populism, Euroscepticism and the far-right.

An excellent commentary. From my current base in Bucharest, following the elections, let me add that the ability of the PSD to govern in an unfettered way in the next year will also be constrained by two factors. The first is the ‘cohabitation’ of power with the centre-right President Iohannis. Secondly, the continuing pursuit by at least parts of the judicial system to charge and convict public officials of incidents of corruption. Legal difficulties have been a cloud over the PSD leadership in recent years, and is this conflict is likely to come to a head in the near term.

Mark McElwain (M. Sc. LSE in School of Government)

Thank you, Mark! Indeed, very good remarks!

We will see how these issues will play out for the social democrats.

The table with the seats in Parliament is very confusing. Does it refer to vote share and seats in camera deputatilor or the senate? Awfully low numbers of seats when if I am not mistaken the Romanian parliament chambers are bigger than that ???

Hopefully it’s a little clearer now, but these are basically partial results as the full results aren’t available for a while after the vote.