The leadup to Spain’s European Parliament election campaign has been dominated by questions over the future of the country’s Prime Minister, Pedro Sánchez. Paul Kennedy and David Cutts examine what the vote could mean for Spanish politics.

This article is part of a series on the 2024 European Parliament elections. The EUROPP blog will also be co-hosting a panel discussion on the elections at LSE on 6 June.

Pedro Sánchez, leader of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), and Prime Minister since 2018, has endured an inauspicious start to his second term as head of the PSOE-Sumar progressive left-bloc coalition government. Sánchez’s woes come almost a year after the inconclusive general election held in July 2023 at which Alberto Núñez Feijóo’s centre-right People’s Party (PP) obtained more deputies than the PSOE, but was unable to attract sufficient support to form a government despite the backing of Vox and two deputies representing small regional parties in the Canaries and Navarra.

Controversially, Sánchez’s return to office came at a cost: the passage of legislation aimed at offering an amnesty to those involved in holding an unofficial Catalan independence referendum in 2017, several of whom were imprisoned. Sánchez presented the shift in policy – he had previously rejected such an amnesty – as a way of further alleviating a situation which he claimed had already improved significantly under his premiership.

For the PP and Vox, the granting of an amnesty constituted a step too far. It enabled Sánchez to cling on to power by offering clemency to Catalan figures who had acted unconstitutionally, jeopardising the unity of the Spanish state. Moreover, the PSOE had also called on the parliamentary support of Euskal Herria (EH) Bildu, heir to the political wing of the Basque terrorist organisation ETA, which had wound itself up in 2018.

Alongside the political fallout from the amnesty law and the suspension of former minister José Luis Ábalos, who refused to resign over a bribery scandal, the new coalition government, hamstrung by a fragile parliamentary majority and an inability to produce a budget for 2024, has simply struggled to “hit the ground running”. And with recent Galician elections bolstering Feijóo’s leadership of the PP and the growth of Basque nationalists EH Bildu in regional elections only adding to Sánchez’s political problems, it seemed likely the ensuing European elections could place even more strain on the coalition’s tenuous parliamentary majority.

Sánchez’s “step back”

Yet just six weeks before the European poll and in keeping with the current unpredictability of Spanish politics, Sánchez shocked his own party, coalition partners, foes, fellow Spaniards and political observers across the globe. In a letter posted on X, just hours after a Madrid judge had opened a preliminary investigation into the business affairs of his wife, Maria Begoña Gómez, Sánchez announced that with immediate effect he had suspended his public duties, required a five-day break to consider his political future and was considering resigning.

He attacked the source of the complaint, Manos Limpias (Clean Hands), whose leader had not only had links to the far right but had in Sánchez’s words based the claims of corruption against his wife on “alleged reporting” from “overtly right-wing and far-right” news sites. Simply put, Sánchez accused his political opponents of plotting together to engineer his “personal and political collapse by attacking his wife”.

Both the PP and Vox dismissed Sánchez’s “stepping back” from public duties as an absurd political stunt designed with crucial forthcoming elections in mind, presenting it as the stratagem of an autocrat capable of anything to remain in government. It nevertheless soon emerged that Sánchez had kept even his closest political confidants in the dark. So when, after his “period of reflection”, Sánchez announced his decision to remain and fight more vociferously against those “who peddle false information and danger political life and democracy”, his supporters reacted with palpable relief.

The European election campaign

The political fallout from Sánchez’s five days of contemplation has been somewhat predictable. Right-wing opponents have stepped up their personal attacks, despite Sánchez calling for a national debate on “regenerating democracy” and an end to bullying and harassment by the media and courts. Allies on the left have insisted on bold action and reforms of the courts including revamping the mechanism for the renewal of Spain’s highest legal committee (the General Council of the Judiciary) which appoints judges. This body has experienced years of deadlock due to the PP effectively blocking a solution.

Whether Sánchez takes this opportunity to reboot the government remains to be seen, yet his decision to lay bare his emotions and upset at the escalating attacks on his wife appears, at least in the short term, to have resonated with the electorate. Opinion polls, which have been unfavourable to the PSOE within the context of opposition attacks on the amnesty law, have rebounded, placing the PSOE within striking distance of the PP.

In the Catalonia regional elections on 12 May, evidence that support for the Socialists had strengthened since Sánchez’s period of contemplation were borne out in the final results. With 42 seats and nearly 28 per cent of the vote, the Socialists secured a clear victory, obtaining its best result in two decades, thereby striking a blow to the independence movement in Catalonia, which lost its absolute majority in parliament.

Yet, reflecting the increasingly polarised politics of Spain, Sánchez remains a marmite figure and a vehicle for the mobilisation of the right. The PP announced that it would hold a rally on the first Sunday of the campaign against Sánchez “for having his government, his party and his entourage under suspicion of corruption”.

Divisions on the left

Going into the European elections, both the PP and PSOE remain dominant within their respective political blocs. While the forces to the PSOE’s left – Sumar and Podemos – remain steadfast in their opposition to a PP-Vox alternative administration, they are far from united.

Disagreement between Sumar and Podemos over a Podemos appointment to one of the five ministerial posts reserved for them in the coalition government led to Podemos breaking away from Sumar. Chastening regional election results in Galicia and in the Basque region where both Sumar and Podemos fielded separate candidates (they will do the same in the European elections to the detriment of both) then followed, exposing Sumar’s weak local organisational structures.

Aside from the split with Podemos, factionalism and discontent within Sumar has only amplified, with the Communist-led Izquierda Unida voicing serious concerns about the party’s direction. Since the 2023 general election, Sumar’s leader, Yolanda Díaz, has struggled to implement an organisational format capable of overcoming disagreements between regional left-leaning parties on institutional appointments.

In the run-up to the European elections, rifts with Izquierda Unida and to a lesser extent other regional forces have emerged over both the selection of candidates and their positions on the European election list. This has somewhat overshadowed Díaz’s attempts to refresh the leadership group and build an outwardly “green” political profile ahead of the European elections that remains distinct from that of the PSOE. Meanwhile, Podemos, which made its breakthrough at the European elections a decade ago, appears in steady decline.

The PP and Vox

On the right, the PP remains in pole position and will undoubtedly frame the European election as a referendum on Sánchez, alleged corruption and the amnesty law to exert maximum pressure on the government’s exiguous legislative majority.

Vox, which since the general election result has also been immersed in its own internal recriminations and infighting, will no doubt double-down on Sánchez but may also seek to exploit Feijóo’s perceived double standard on the amnesty law after it emerged that he privately approved of awarding the exiled former regional President Carles Puigdemont, leader of the separatist Junts per Catalunya (Together for Catalonia) a conditional pardon.

Like other far-right parties across Europe, Vox has been actively courting disgruntled farmers, whose vocal protests at the EU’s environmental transition agenda have affected Madrid and other European cities. If the parties manage to move away from domestic issues, Vox’s ability to position itself as the party best placed to fight for farmers against “bureaucratic Brussels” and its vehement opposition to the 2030 agenda and the European Green Deal – including the Nature Restoration law – could eat into the PP vote.

This is despite the PP similarly opposing many of these key strands of EU environmental policy in Strasbourg. Moreover, clear water between the PP and Vox over support for the United Nations 2030 Agenda for sustainable development (which only the latter opposes) and objections to free-trade agreements, which Vox claims are undermining Spain’s agricultural industry, could also split the right-bloc vote.

Implications for Spanish politics

Given tensions on the left, the so-called progressive challenge to the right on the European Green Deal and climate change is likely to come from Teresa Ribera, Spain’s environment minister, who heads the PSOE’s candidate list. The underlying politics is clear. With Sumar struggling to distinguish itself from its coalition partner, Sánchez is seizing the opportunity to burnish his own party’s progressive credentials and highlight his stature as the leader of the left in Spain.

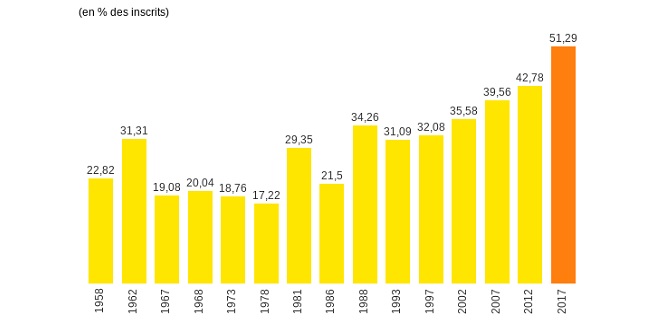

Whether this strategy is effective for the PSOE on 9 June remains to be seen, given the perennial challenge of turning out its vote and the wider potential apathy towards the elections themselves. Nonetheless, given the coalition’s precarious majority and the increasing unpredictability of Spanish politics, what happens on 9 June could have significant ramifications moving forward.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Union