The recent scandal surrounding Russian state-sponsored doping highlighted deep rooted issues affecting international anti-doping procedures in sport. Slobodan Tomic argues that the key problem lies in the failure of the current anti-doping regime’s institutional design to specify hierarchies of accountability. To match powers with responsibilities, he suggests that we should avoid framing the reform as a debate over the role of one stakeholder – the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) – and instead consider the wider picture, while clearly defining the role played by individual states.

The discovery of a state-sponsored doping scheme for Russian athletes, and the controversy surrounding the use of Therapeutic Use Exemptions by athletes, are simply the latest scandals that have precipitated talk of reforming the system for tackling doping across world sport, and of reforming its chief regulator, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). The ongoing debate over the issue regularly includes exchanges assigning blame for recent scandals, as well as a multitude of ideas for improving the present system, but the question of the accountability architecture of the anti-doping regime has barely been raised.

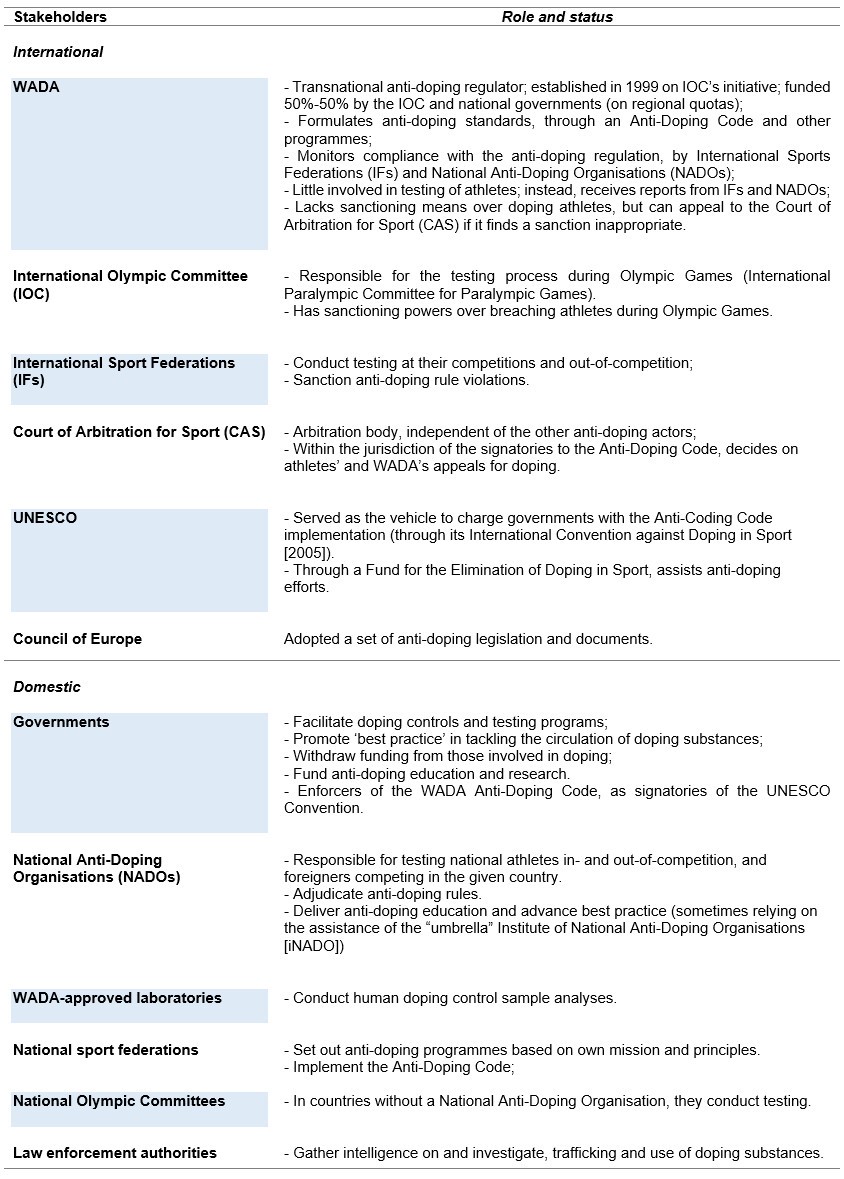

Talks of future reform have included the possibility of replacing WADA with another body, within or outside the International Olympic Committee (IOC). However, several questions are still outstanding: would this new body need additional powers? How would resources be increased to support the inspection of athletes? Furthermore, WADA is not the sole, but only one in a multitude of stakeholders in the international anti-doping regime, as illustrated in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Network of stakeholders in the anti-doping regime

Source: Adopted from WADA’s website. Table compiled by the author.

Since the state does not represent the (sole) locus of authority and the stakeholders’ relationships are fragmented and interdependent, this regime is a polycentric one. As such, it suffers from inherent coordination difficulties, with serious enforcement as well as legitimacy challenges. Yet, despite these ‘inherent’ difficulties, the key problem in the current anti-doping regime lies in the failure of its institutional design to specify the accountability hierarchies among stakeholders. In short, as highlighted in an oft-cited paper, who is to be held to account in the pursuit of anti-doping policies, to whom, for what, by what standards, and with what effects?

Should governments, who fund WADA with a 50% contribution, hold the latter to account for the outcomes of anti-doping policy, or should it be the IOC, which initiated the creation of WADA in 1999 and which provides the other 50% of WADA’s budget? Or should this be an ’umbrella’ international organisation such as UNESCO or similar? Should WADA be held accountable at all for those failures that are beyond its powers and control? Regrettably, the legislation defining the institutional design of the anti-doping regime is silent on such issues.

Moreover, the absence of clear accountability arrangements has left the door open for turf battles over the role of the principal among stakeholders. WADA’s efforts have clearly been to establish itself as the main locus of authority in the anti-doping world, whereas the rhetoric and actions of other stakeholders, such as the IOC, demonstrate a similar intention which would then render WADA’s position ‘sub-ordinate’. National governments, on the other hand, have not made such pledges so far, but their role should not be dismissed given the history of major interventions of national officials in previous crises in the anti-doping world (for example, during the creation of WADA in 1999).

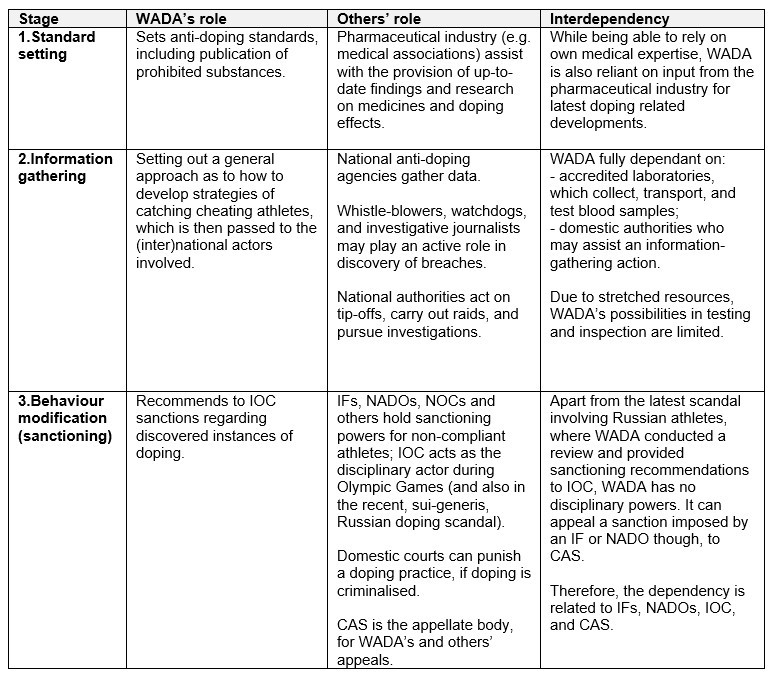

While skilled ‘turf battling’ may increase an actor’s legitimacy to claim de-facto leadership, under a high degree of polycentrism this can increase the gap between the real regulatory possibilities and the perceived duty to solve problems that arise. Consider the range of international and domestic stakeholders in all three phases of the regulatory process – in standard-setting, in data collection, and in enforcement – that WADA is dependent upon (Table 2).

Table 2: WADA’s interdependencies across the regulatory cycle

Note: The three stages are adopted from Hood et al. Information gathering mostly consists of collecting and testing urine and blood samples. Human intelligence gathering is a much smaller component, although growing in importance. Table compiled by the author.

Whereas the low rate of positive tests of athletes (often around 1%) suggests a failure in the anti-doping system, it should not be forgotten that implementing an anti-doping system is highly complex. It unfolds across national territories, athletes provide ‘whereabouts’ information for out of competition tests, conducted without notice; samples have to be safely transported and tested, then sanctions imposed in the event of an adverse finding.

The whole process is subject to appeal both within the rules of the commissioning organisation and then at CAS. Conflicts of interest are inherent in the system: an IF or an NOC makes important decisions about who and when to test, and what sanctions to impose, but it is not in their interests for their biggest stars to test positive and be suspended from major championships (independent anti-doping processes are yet to be developed). It is clear then that WADA has neither the powers, nor the resources, to effectively drive such a process.

Yet, having portrayed, and probably having established itself over the previous period as the major stakeholder, WADA has become the prime addressee in analyses of the troubling state of anti-doping. Despite general support for the continuation of its work, the impression is also that a wider public finds WADA responsible for the status quo as well as future action in tackling doping. Others, such as individual IOC members, have pushed this notion further, pointing to WADA as the main culprit for the anti-doping regime breakdown. However, these perceived accountabilities are not grounded in the formal design but result from non-formalised stakeholders’ day-to-day muddling through.

Instead of framing the question of reforms as a debate over one stakeholder, further discussion of reforms would benefit from considering the wider picture of the anti-doping regime. The roles and expectations of all stakeholders need to be specified, and appropriate accountability arrangements assigned. This would include defining the role of the state in the transnational anti-doping regime, international organisations’ roles, and scope for action of the other stakeholders such as WADA and the IOC. It would then be possible to match the powers with responsibilities for the overall anti-doping regime (and parts of it).

Interdependences, inherent to polycentric regimes, will by no means disappear, but they will become more manageable. Having clearer lines of responsibility and stakeholders’ roles can improve mutual collaboration and reduce the scope for blame-games, dispelling much of the current unease within the anti-doping world.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Slobodan Tomic – I Trust Sport / UCL

Slobodan Tomic – I Trust Sport / UCL

Dr Slobodan Tomic is a Research Analyst at I Trust Sport, a London based sports governance consultancy, and a Teaching Fellow at the School of Public Policy at the University College London (UCL). He obtained a PhD from the LSE Department of Government.