What has motivated Romanians to hit the streets in numbers unseen since the 1989 Revolution? Mihnea Stoica presents new survey evidence showing a breakdown of the protesters’ incentives. He concludes that the topic of corruption has developed into one of the main political cleavages prompting political action.

What has motivated Romanians to hit the streets in numbers unseen since the 1989 Revolution? Mihnea Stoica presents new survey evidence showing a breakdown of the protesters’ incentives. He concludes that the topic of corruption has developed into one of the main political cleavages prompting political action.

The last few days have seen massive protests all around Romania, triggered by the government in Bucharest attempting to decriminalise certain corruption offenses through an emergency ordinance, an act which was seen by many as something approximating a personal favour for Liviu Dragnea, the president of the Social-Democrat Party (PSD), given his conviction for electoral fraud almost two years ago.

After having their first candidate for Prime Minister rejected by President Klaus Iohannis in December last year, the current civil unrest seems to be the second major challenge for the Social-Democrats in just two months after winning the national elections with a very comfortable majority. His criminal record kept Dragnea away from becoming Prime Minister, but instead he made it very clear that, de facto, governmental decisions would be taken by him at the party headquarters, thus leaving Prime Minister Sorin Grindeanu with nothing more but a de jure position in the newly formed cabinet.

Despite his initially uncontested position both within the governmental decision-making process and within his own party, Liviu Dragnea is now facing pressure from both sides. It becomes clearer by the day that the more street protests continue, the more the government will dedicate time to explaining its initial decision, thus putting all other matters lower down its agenda, including the national budget.

Romanian parliament building, Credit: Les Haines (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Romanian parliament building, Credit: Les Haines (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

The PSD’s strongest asset in winning the elections was precisely the economic measures that it promised to implement and that would primarily benefit those in a difficult economic situation. Not being able to carry out such a promise would seriously upset the party’s core electorate, a situation that might rapidly become intolerable for members of the cabinet, who are either stuck with communicating on anti-corruption measures or who are not communicating at all. Even after Prime Minister Grindeanu publicly announced that he would take measures to cancel the effects of the initial decision, hundreds of thousands of Romanians still took to the streets to show their lack of trust in the government.

The other major problem of the PSD leadership stems from inside the party, as quite a number of young and prominent members showed their disapproval with the actions of the government and directly accused Dragnea of jeopardising the party, especially when it comes to efforts at connecting with young voters. The first one to resign from the PSD was former minister and MP Aurelia Cristea, who became popular once she introduced the law banning smoking in public places, an initiative widely supported by the progressive and young electorate.

MEP Sorin Moisa, another left-wing politician very much appreciated for his professionalism, announced his resignation as well. Florin Jianu, the government’s business and trade minister, also resigned from his position in the cabinet and Mihai Chirica, the social-democrat mayor of Iași (one of Romania’s major cities) declared that he would join protesters if the government did not change its mind about decriminalising corruption offences. The PSD therefore shows signs of what one might call two shades of red, with protests allowing progressive profiles to surface in a party that has constantly been accused of being strongly conservative.

Interestingly enough, the opposition has not managed to capitalise too much from the disarray that the street protests generated for the PSD. Both the National Liberal Party (PNL) and the Save Romania Union (USR) seem to be experiencing difficulties in drafting a coherent communication strategy – other than just holding up placards with the word “Corruption” in the building of the Parliament whenever they see a member of the cabinet passing by in the corridors.

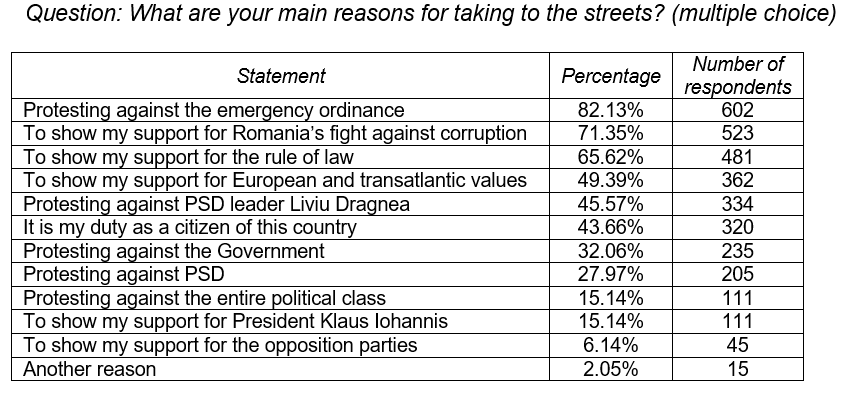

Their intention to fully identify themselves with the protesters might also be risky, since those on the street are also demanding a renewal of the entire political class. An online survey conducted by the Department of Communication, Public Relations and Advertising of the Babeș-Bolyai University, together with Kieskompas B.V., shows that only around 6% of those who prostest take to the streets to show their support for the parties in opposition. Most of them have declared that they protest primarily against the ordinance (more than 82%) and to support Romania’s fight against corruption (71%).

Table: Survey responses from protesters in Romania

Source: Department of Communication, Public Relations and Advertising of the Babeș-Bolyai University/Kieskompas B.V. (N=733)

The protests show that the topic of corruption has developed into one of the main political cleavages which prompt political action – either in the voting booth or on the streets. It might very well be that the legitimacy of the Grindeanu Government has been irrevocably compromised and that any future action, regardless of its nature, will face resistance or at least distrust.

The solution lies within the PSD, which will most probably reshuffle the cabinet, but it remains to be seen how the party will choose to present itself after the turmoil it has been going through. A young and progressive team might represent a dangerous choice for Liviu Dragnea, since it would put at risk his already shaky authority. But keeping a conservative leadership might further emphasise the differences between the two shades of red, with the risk of breaking up the PSD.

Regardless of how the events evolve, Romanian politicians might have learned the hard way that their actions are not legitimised only by elections once every four or five years, but that they constantly need to communicate with the citizens they represent.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Mihnea Stoica – Babes-Bolyai University

Mihnea Stoica – Babes-Bolyai University

Mihnea Stoica is a Research Assistant at the Department of Communication, Public Relations and Advertising of the Babes-Bolyai University in Cluj-Napoca, Romania. He holds an MSc in Comparative European Politics from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and has worked as an MEP adviser at the European Parliament. His research interests revolve around political communication, focusing mainly on populism, Euroscepticism and the far-right.