The migration crisis has posed a number of challenges for European countries, but what lessons can be learned from previous experiences with large scale migration? Mikkel Barslund, Matthias Busse, Karolien Lenaerts, Lars Ludolph and Vilde Renman present evidence from a study of the integration of Bosnian refugees in Europe following the Balkan wars in the 1990s. They find that with the right integration policies and labour market conditions, it is possible to achieve a high level of integration among refugees within a short period of time.

In 2015, Europe experienced the largest influx of refugees since the Balkan wars in the early 1990s. While arrivals were down in 2016, the security situation in the Middle East and the instability in North Africa and elsewhere mean that Europe will play host to refugees for the foreseeable future. Quite apart from the considerable humanitarian issues at stake, this commands European countries – both out of self-interest and in the interest of refugees – to facilitate wider societal integration. Labour market integration of newcomers plays a key role in achieving this objective.

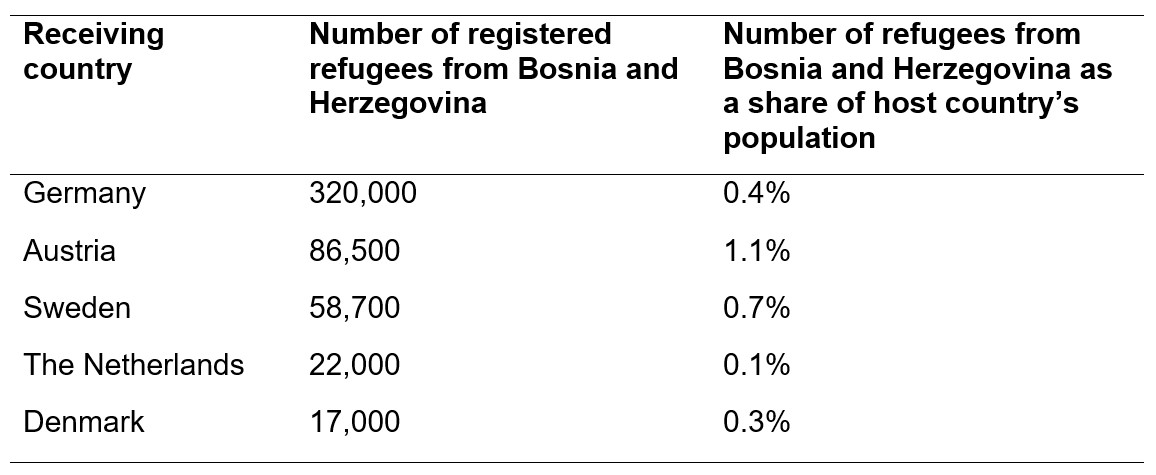

The situation in the early 1990s, when over the course of a brief period of time 1.2 million Bosnians fled the country as war refugees and more than half a million sought refuge in Western Europe, was not so different from the situation today. Moreover, there is significant overlap among countries affected by the two refugee waves. Austria, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden all saw a large absolute and relative influx of refugees in both 2015 and between 1992 and 1995, when the bulk of Bosnians arrived in Western Europe (Table 1).

Table 1: Overview of registered refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992-1995)

Source: Barslund et al. (2016), Valenta and Ramet (2011) and the OECD population database; population data from 1992.

In a recent study, we trace the integration experience of Bosnian refugees from the Balkan wars in those five countries to draw lessons for the current wave of refugees. Integration is a slow-moving process. Looking closely at Bosnian refugees enables us to see past immediate integration outcomes and take a longer-term view.

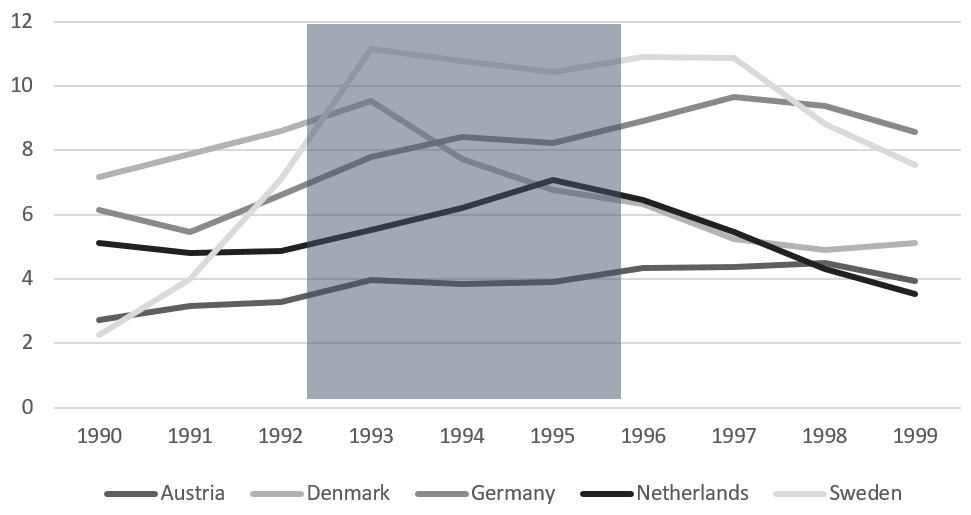

We drew on international published research but, more importantly, also combed through a significant amount of national sources. The five countries also make for a particularly interesting comparison because they differed in important ways when the Bosnians arrived (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Unemployment rates at the time of the Bosnian war

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook

Sweden had just entered what was going to be a prolonged economic crisis. Unemployment was high in Denmark too, but the subsequent path was one of falling unemployment rates and high growth for one decade afterwards. The Netherlands as well as Austria were running at or close to full employment, and Germany was entering the period of being labelled ‘the sick man of Europe’.

This situation was reflected to some extent in the approach to the initial reception of the Bosnian refugees. Bosnian refugees received temporary protection at the time of their arrival in all Western European countries. This was mainly a political compromise. For host countries, it was the only way of dealing with the large influx of refugees without amending their asylum systems or overburdening them. The UNHCR had deeper concerns. The organisation wanted to push the issue of burden-sharing of refugees across Europe. In fact, discussions at the time bear some resemblance to those taking place within the EU today. Temporary protection left the door open to involving those Western countries that had not initially experienced an influx of refugees displaced from the former Yugoslavia. This strategy turned out to be largely unsuccessful. An additional concern was whether granting refugees permanent residency upon arrival would institutionalise the widespread ethnic cleansing going on in parts of Bosnia.

Despite the consensus on provision of initial temporary refuge, there were vast differences in the legal and institutional approach to dealing with the influx of Bosnian refugees. Three broad categories emerged within the selected sample of countries. Sweden granted refugees permanent residency and labour market access shortly after arrival. Austria, Denmark and the Netherlands converted the initial temporary asylum with limited access to labour markets into permanent residency and full access to labour markets after a few years. Finally, Germany never intended to host Bosnian refugees permanently and repatriated the vast majority of them as soon as the war ended.

With this background, one may have expected very different outcomes from the integration process. Germany apart, however, the overall story is one of long-term successful integration in the host countries. Differences are most pronounced with regard to the speed of the integration process. Labour market outcomes, measured by employment rates, differ among countries in ways that can be linked to both integration approaches and initial labour market conditions.

Employment rates picked up fast in Austria where in 1998, 64 percent of Bosnian refugees were in employment. For the three other countries, integration had barely begun (Figure 2). Sweden’s double-digit unemployment rate was a factor, whereas the lack of integration in Denmark and the Netherlands – both being close to full employment in 1998 – may reflect a lack of integration measures early on.

Figure 2: Employment rate of former Yugoslav nationals in 1998 in various host countries

Source: Angrist and Kugler (2003) and Eurostat Labour Force Survey

Employment then picked up in all countries, albeit at a different pace. In Austria, medium-term labour market outcomes around ten years after the end of the Bosnian war were already on par with the native-born population. In Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden, Bosnians still participated significantly less in the labour market and showed higher unemployment rates but the gap to the respective native-born population clearly began to close, in particular for the younger age groups.

Recent evidence from Denmark and the Netherlands indicates that educational attainment of young and second-generation Bosnians is on a par with or even exceeds that of the respective native population. More time is needed to assess if the gains in educational achievements of the second generation translate into higher employment rates, but the initial assessment is encouraging. We did not find any evidence on educational attainment of second generation Bosnians in Sweden.

However, for three of the four countries the process of integration seems to have been completed within one generation. This is rather fast and it is well worth exploring further the determinants of these positive outcomes, particularly because such a catch-up is not found for other immigrant groups. One important factor in explaining this catch-up could well be the fact that Bosnians were generally better educated than other refugees. There is some evidence from Germany that the same is the case for the recent Syrian refugees.

Overall, our results point to four interesting findings. Under favourable integration policies and labour market conditions, employment rates can reach those of the native population in little more than a decade (the Austrian case). Granting the right to work quickly upon arrival is important, but failure to do so can be overcome over time (Denmark, the Netherlands). Initial unemployment levels in host countries are important for initial labour market integration (the case of Sweden): a finding which is not surprising, but important given the European debate on distribution of refugees. Finally, second-generation Bosnians, or those who arrived at a young age, perform roughly on a par with native-born cohorts. We deem this to be a sign of a completed integration process.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Mikkel Barslund – Centre for European Policy Studies

Mikkel Barslund – Centre for European Policy Studies

Mikkel Barslund is Research Fellow in Economy and Finance at the Centre for European Policy Studies.

Matthias Busse – Centre for European Policy Studies

Matthias Busse – Centre for European Policy Studies

Matthias Busse is a Researcher in Economy and Finance at the Centre for European Policy Studies.

Karolien Lenaerts – Centre for European Policy Studies

Karolien Lenaerts – Centre for European Policy Studies

Karolien Lenaerts is a Researcher in Economy and Finance at the Centre for European Policy Studies.

Lars Ludolph – Centre for European Policy Studies

Lars Ludolph – Centre for European Policy Studies

Lars Ludolph is a Researcher in Economy and Finance at the Centre for European Policy Studies.

Vilde Renman – Centre for European Policy Studies

Vilde Renman – Centre for European Policy Studies

Vilde Renman is Administrative and Research Assistant at the Centre for European Policy Studies.

The premise that European refugees legally migrating into another European country (i.e., people of similar cultural/historical background) is somehow the same as non-European economic migrants illegally entering Europe (i.e., people of dissimilar cultural/historical backgrounds), is a farce. There is no valid connection that can be made. There is no historical reference where mass uncontrolled migration of people of dissimilar cultural backgrounds has been successful; it is just a allusion/delusion. On the contrary, historically speaking, mass uncontrolled migration of people of dissimilar backgrounds has led to violence (ex., European settlers into the Western Hemisphere, Ottoman Turks entering Byzantine Greece, English into modern day Australia, Americans into the Kingdom of Hawaii, etc…).

People like to point to the Potsdam Agreement that had ethnic German refugees to leave other parts of Europe and to migrate into Germany. However, this involved people of similar backgrounds.

This article is logically invalid, and it can only be made valid by removing the key variable of “historical context”; which by doing so makes this article a fraud.

Seriously Bosniaks are a white people nation, you dont need that much brain power to figure out some things you know. You should read Bosniaks history to understand some things, from Bosnian kingdom (900-1463) to todays independent Bosnia. Bosniaks come from a kingdom and they have a legacy,

Also their name is Bosniak (Bosniaks in plural).

Simply an academic suspension of disbelief, whether intentional or thru negligence.

If these Bosniaks had illegally migrated to (for example) Saudi Arabia or Syria or Pakistan or Iran or Iraq or Bangladesh, and the Bosniaks then demanded all forms of unearned/undeserved benefits, would the integration have been successful? No! Would the Bosniaks bringing their European values/religion/culture to those countries not result in clashing with the locals of the above mentioned countries? Yes! So why is the opposite expected when the roles are reversed and the new wave of economic migrants arrive in Europe?

Bosnians were being ethnically cleansed in part because they were seen by Serbs as non Christian and non European (Muslims supposedly descended from Ottoman Turks)

As a Bosniak girl with Serbian grandmother, I can assure you, you’re wrong. It was all about the power.

Yes but I understand that this was the reason used to incite violence by those who wanted power?

Bosniaks aren’t dependents of ottomans.Bosniaks are one of the oldest peoples in all of Europe.Our history predates the Greek and Roman civilizations by thousands of years.We are Illyrian not slavs.The name Bosniak or Bosnia comes from Illyrian word Bosona meaning the land of water.Our mythology is based on thousands of years worth of cultural heritage.There is a reason archeologists call this part of the Balkans the Old Europe..Our ancestors are the Butmir and Vinca cultures.IGENEA and the Human genome project confirmed this in their study.Ancient Danubian culture.Bosnians are 50%Illyrian at some place over 65% 20%teuton (germanic) 15%Celtic and less then 10%slav.We speak a slav language because the migrated here in the late 6th century and destroyed our state Illyria and abolished our native language.We have lived in whats today Croatia,Serbia,Montenegro,Kosovo,Slovenia,and parts of Albania and Macedonia long before those countries even existed.Our ancestors had their own religions that were later slavanized and christianized.The Bosnian church was a separate entity and were called Heretics by both Orthodoxy and Catholic churches.Its combined pagan and christian religions.When Islam came it was something close to what they all ready believed thats why the massive conversion to Islam.Today Bosnians aren’t migrants or decentness of Ottomans but an Authentic people in Europe a Native population of the Balkans.Our lands were stolen and just as 20 or so years ago what is left of it was tried to be taken away from us too.Istra in Croatia was Histra Dalmatia was Dalmatae Bosnia was Bosona Montenegro was Zeta Serbia was Arša Kosovo was Dardania Parts of Albania and Macedonia were Albanoi and Bassania.We are a people of Europe that has never attacked anyone a people in Europe with 0 crimes under our belts a people that has kept ancient European traditions to this very day.Look at the Genetics study of European peoples and you will see that we are one of the oldest in all of Europe in the same class as Basques

To the author:That you are comparing people from the Middle East to Bosnians dislpays that you do not have any knowledge about the difference between the cultures. I am a Bosnian and I see that you do not know or refuse to know what you are talking about.Look at the map please and take notice that Bosnia and Herzegovina is in he Eastern Europe. As human being or a woman a woman I am free to say or do anything except for a theft, murder and stuff like that. I can choose any kind of life that I want to.I can be a feminist as well and openly talk about it. Please stop embarrassing yourself in this way.