The European Commission has published a ‘White Paper on the Future of Europe’ ahead of the Rome Summit schedule for 25 March. According to Iain Begg, the main contribution of the paper may be to push the EU27 to accept the reality of an EU without the UK, but in doing so it sets out scenarios that, had they been plausible options only a year ago, would have been music to British ears.

Last week, the European Commission published its White Paper on the Future of Europe (WP), its attempt to set out the options for the development of the European Union. It explicitly rejects the narrow choice between more or less, offering instead a range of scenarios described as ‘neither mutually exclusive nor exhaustive’. The WP’s opening line comes perilously close to being an epitaph, stating: ‘for generations, Europe was always the future’, oddly reminiscent of David Cameron’s valedictory statement to the House of Commons, ‘I was the future once’.

The overt purpose of the WP is to stimulate debate how to recast the EU. It can, equally, be read as a means of waving goodbye to the UK and moving-on. The document looks forward to the meeting later in March when ’27 Heads of State and Government meet in Rome to mark the 60th anniversary of our common project’ – Theresa not invited.

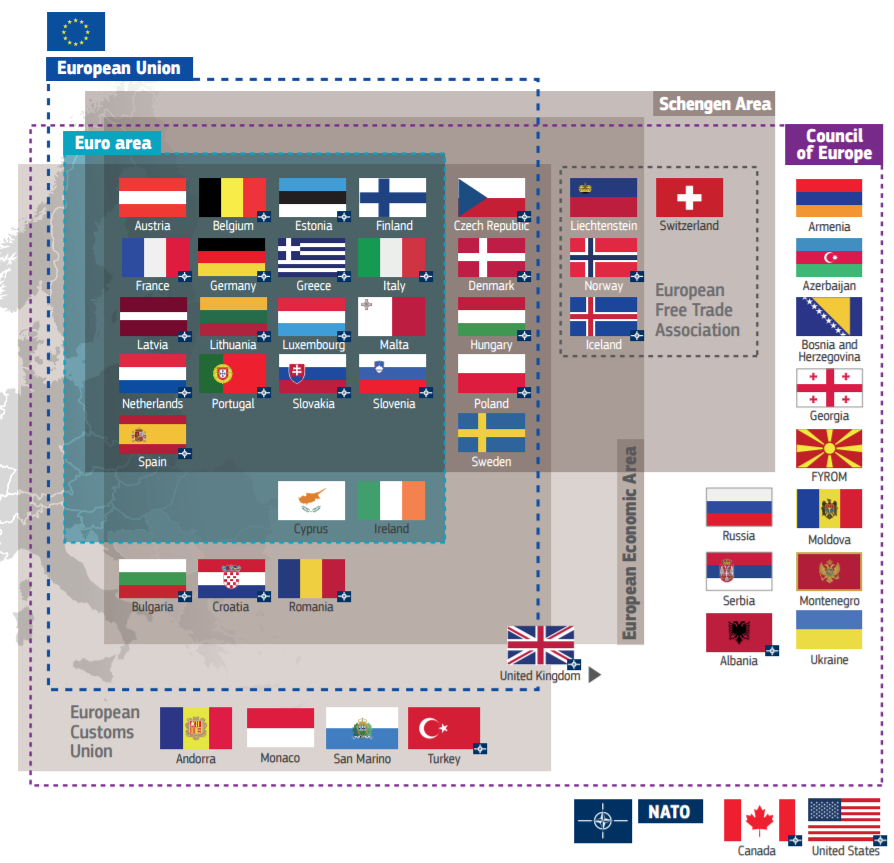

In a clever chart showing who belongs to what (euro area, Schengen, European Economic Area, the customs union), a lonely looking UK is positioned in a corner pointing outwards to membership of only the Council of Europe along with the likes of Armenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Ukraine… and Russia.

Figure: Overview of Europe in the Commission’s White Paper

Source: European Commission

The five scenarios presented range from narrowing the scope of the EU to a substantial deepening of its role. Strikingly, given the tradition of aiming for a single model of integration, they include two under which participation in key policy areas would be optional, and only one which would constitute markedly ‘more Europe’. Moreover, the WP is careful not to convey a preference, something that, for connoisseurs of UK practice, is more in line with the consultative approach of a Green, rather than a White Paper.

In lionising Europe’s achievements (and it is striking that throughout the document, the expression ‘Europe’ is used much more often than ‘EU’ or ‘European Union’), the WP cites many in which the UK has played a prominent and sometimes pivotal role: the single market, the research programmes, the Paris climate change deal, international diplomacy and NATO. At first sight, the message could be ‘see what we have achieved’, but to British eyes might also be ‘look at what you helped us achieve…and you risk jeopardising by leaving’.

Much of the first half of the paper is about the challenges and threats Europe has to confront: ageing, security, economic transformation and doubts about the social model. There is also an admission that trust in the EU has waned and that too often there has been a gap between the expectations placed upon the EU and its capacity to deliver.

Several passages emphasise the need to deliver on promises, a theme already evident in Jean-Claude Juncker’s two State of the Union addresses and in the September 2016 Bratislava declaration in which the EU 27 started to map out their future without the UK.

As we all know, having been told so endlessly, ‘Brexit means Brexit’, but an intriguing question is nevertheless how good a fit the various scenarios would be for the UK. One, a retreat to ‘nothing but the single market’ could well appeal to all but the most extreme Brexiteers.

It envisages an EU focused on free movement of goods and capital, but with restrictions on movement of services and people, alongside no common migration and refugee policy. Ironically, the prospect of restrictions on free movement of services might even be too little for those in the UK concerned to curb migration, but still anxious to optimise access to the EU market for the City of London.

Arguably, a majority in the UK would be happy, too, with the scenario entitled ‘those who want more do more’ insofar as it enshrines the principles of what is known as differentiated integration, under which some groups of EU Member States collaborate more intensively, while others do not. It is, manifestly, contrary to the notion of ‘ever closer union’ that elicited so much opposition in the UK during the referendum. Indeed, the section on the way forward reiterates the alternative slogan of ‘unity with diversity’, so often overlooked in UK debate on the EU.

Among the other three scenarios, it is hard to believe that ‘carrying-on’ with its mix of status quo and muddling-through is convincing: surely the one conclusion to be drawn from the years of drift is that something has to change. The UK would feel most uncomfortable with ‘doing much more together’, but then so would several other Member States.

That leaves ‘doing less more efficiently’ which combines some ambitious elements (such as a European defence union) likely to be unappealing to the UK, with a much reduced role in employment and social policy that would be welcome on this side of the Channel.

What should we make of the paper? As a contribution to the debate on the future of Europe it is balanced and, in some ways, astute in highlighting the dilemmas facing the EU. However, it is no more than a starting-point and readers will look in vain for strong signals about where the EU is headed. Further ‘reflection’ papers are promised on social Europe, defence, harnessing globalisation, the future of EU finances and on deepening EMU.

The last is especially intriguing, because it is portrayed as a follow-up to the June 2015 Five Presidents’ report. So far, the follow-up has been relatively limited, but the original plan was for there to be a White Paper this spring specifically on completing EMU. It may be that the unresolved disputes among Euro Area members about contentious issues, such as risk sharing or institutional development, are too far from resolution for firm proposals.

The White Paper’s main contribution may therefore be to push the EU27 and the many interests who shape opinion and policies to accept the reality of an EU without the UK. Yet it is also tantalising in setting out scenarios that, had they been plausible options a year ago, would have been music to British ears. Who knows what might have been?

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: A version of this article appeared at UK in a Changing Europe. The article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

About the author

Iain Begg – LSE, European Institute

Iain Begg – LSE, European Institute

Iain Begg is a Professorial Research Fellow at the European Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science, and Senior Fellow on the UK Economic and Social Research Council’s initiative on The UK in a Changing Europe.