The British electorate is generally portrayed as being more fragmented on the left than it is on the right, with Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the SNP and the Greens, among others, all competing for the same voters. Ahead of the UK’s upcoming general election on 8 June, John Connolly reassesses this picture using British Election Study data. His analysis suggests that a large group of voters on the left who are both anti-EU and anti-immigration could be drawn back toward Labour if the UKIP vote collapses.

The British electorate is generally portrayed as being more fragmented on the left than it is on the right, with Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the SNP and the Greens, among others, all competing for the same voters. Ahead of the UK’s upcoming general election on 8 June, John Connolly reassesses this picture using British Election Study data. His analysis suggests that a large group of voters on the left who are both anti-EU and anti-immigration could be drawn back toward Labour if the UKIP vote collapses.

UKIP campaigners, 2013. Credits: Jennifer Jane Mills (CC BY 2.0)

In September 2016, following the UK’s decision to leave the European Union, the findings of a joint analysis of the British electorate by Opinium and the Social Market Foundation (SMF) were reported in The Guardian. The analysis broke down the British public into eight hypothetical groups based on the political values of each group’s members. The findings were interpreted as troublesome for Labour’s aspirations and the political left in Britain more generally, as the left emerged as more fragmented than the political right and therefore harder to unify around a set of campaign issues.

The accompanying article noted that “three times as many voters now regard themselves as centrist or to the right of British politics as those who see themselves on the left”. However, support for this statement was based on findings that put 45% of people in the political centre, 30% on the right, and 25% on the left. As such, it would have been just as true to say that “almost two and a half times as many people regard themselves as being centrist or on the left as those who regard themselves as being on the right.”

Less questionable was the report’s claim that challenger Jeremy Corbyn is perceived as being more to the left than his main opponent, Prime Minister Theresa May, is perceived to be to the right. However, perceived political proximity is only one of many factors that determine electoral choice. The surprising level of support for candidate Bernie Sanders throughout the 2016 presidential primaries perhaps shows how such perceptions can be quite ephemeral, especially if a campaign message resonates.

The various groupings of the British electorate were relatively subjective. One group, projected to be the largest at 26%, had the moniker “Common Sense,” and was composed of members with “more traditionally Conservative views”. Another conservative group was dubbed “Our Britain”, with members being described as “ethnic nationalists.” These two groups, according to the report, were the largest at 26% and 24% of the British public respectively. The other groups on the political right were Free Liberals (7%) and New Britain (6%). The groups identified as on the political left were Democratic Socialists (8%), Community (5%), and Progressives (11%). One centrist group was identified called Swing Voters (7%), leaving a residual of 6% that did not fit into the framework so that, strictly speaking, there were actually nine total groupings of the electorate identified.

The underlying message is that since the left is more fragmented across issues like immigration and the EU, it will be harder for Labour to put together a winning coalition, compared to a Conservative Party that can readily tap into the two largest blocks of the electorate. But putting aside the problems of mapping the groups to specific parties, how accurate is this depiction of the British electorate as we look toward the general election on 8 June?

Mapping the British public’s views

To explore these issues further, I conducted a latent class analysis of British Election Study (BES) data. The data was compiled just after Brexit last year and was based on responses from around 30,000 participants to a series of questions concerning democracy satisfaction, attitudes toward austerity and income redistribution, respondents’ political positions on a left-right scale, and attitudes toward immigration and the EU. This procedure removes a large part of the subjectivity involved in this kind of electoral breakdown and provides an objective way of deciding the best number of groups. Furthermore, it allows for the use of party identification in predicting group membership.

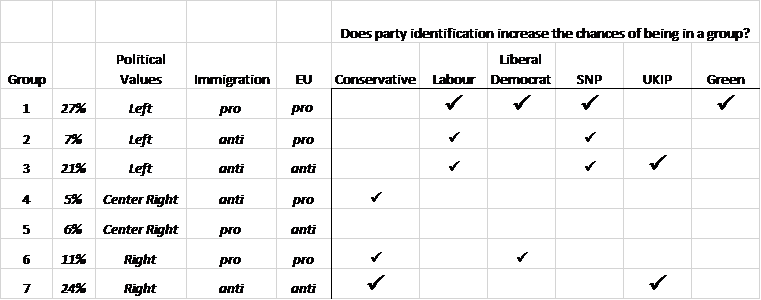

Seven groups of the electorate were identified through this method. These included three groups on the left. The first and largest of these was both pro-immigration and pro-EU, with significant proportions of Labour, Liberal Democrat, SNP, and Green Party identifiers. The second was anti-immigration but pro-EU, while the third was both anti-immigration and anti-EU, with a particularly high proportion of UKIP identifiers, but also including those SNP identifiers who do not share the party leadership’s commitment to the EU. The first of these groups was actually projected to be the largest of the entire electorate (27%), while the third was also substantial (21%).

On the right, there were two small groups, both somewhat centrist in political values, but who differed sharply on both attitudes toward immigration and attitudes toward the EU. This left two other groups that were more conservative but that also differed sharply on the same issues, the largest of which (24%) was both anti-immigration and anti-EU. The overall picture is shown in the table below.

Table: Groups of British voters according to latent class analysis of British Election Study data

Source: Compiled by the author using British Election Study (BES) data

There is little evidence from this picture that one side of the political divide is necessarily more fragmented than the other, although it is true that the largest group on the left is composed of members with divided party loyalties; in short, there is more party competition on the left. While the picture therefore in one respect reiterates well-publicised challenges facing the Labour Party in building a winning coalition in the near term, it also points to opportunities in the long run. Most notably, a large group exists of individuals with left values whose members have been drawn toward UKIP in recent years. These members could constitute rich pickings for Labour if the issue of immigration comes to recede in importance and the dust finally settles on Brexit.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

John Connolly – University of Texas at Arlington

John Connolly – University of Texas at Arlington

John Connolly is a Data Scientist in the Office of Information Technology in The University of Texas at Arlington. He holds a PhD in Political Science.