Midterm elections, such as those due to be held in the United States on 6 November, are often used as a key measure of a government’s popularity. But there is a common perception that even if governing parties suffer poor results in midterms, they are likely to regain some support before subsequent national elections due to the ‘electoral cycle’ effect. Drawing on new research, Stefan Müller and Tom Louwerse illustrate that while this may have been true at one time, recent decades provide little evidence that governing parties will recover from early losses at the end of the electoral cycle.

Midterm elections, such as those due to be held in the United States on 6 November, are often used as a key measure of a government’s popularity. But there is a common perception that even if governing parties suffer poor results in midterms, they are likely to regain some support before subsequent national elections due to the ‘electoral cycle’ effect. Drawing on new research, Stefan Müller and Tom Louwerse illustrate that while this may have been true at one time, recent decades provide little evidence that governing parties will recover from early losses at the end of the electoral cycle.

Next week there will be midterm elections in the United States: President Trump is almost halfway through his term, but the Americans can vote for a new House of Representatives and for about a third of the Senate. These elections are seen as a measure of the president’s popularity. In other countries, too, local or regional elections are used as a measure of the government’s popularity on the national level.

Conventional wisdom is that government parties may lose support at midterms, but then manage to regain some voter support: the ‘electoral cycle effect’. This is based on analyses of midterm elections in the countries where they take place, but the difficulty of such an analysis is of course that local and regional factors also (perhaps fortunately) play a role in local or regional elections. Moreover, it is difficult to compare patterns of this kind between countries, because midterm elections take different forms in different countries. In a recently published research note we therefore investigate the electoral cycle of support for government parties on the basis of opinion polls in 22 parliamentary democracies.

We expected that government parties could initially expect a slight gain in opinion polls during their so-called ‘honeymoon’ period (phase 1 in the figure below). Soon, however, government parties are expected to lose support (phase 2). It is usually not possible to completely fulfil election promises, and voters may punish government parties more harshly for things that go wrong than they reward them for successes. Around the midpoint of the parliamentary period, support reached a low point (phase 3), but in the last quarter of the cycle (phase 4) we expected to see some recovery. This could be because governments plan favourable measures (such as tax cuts) in the run-up to the next elections, but also because voters return to their party.

We tested these expectations on the basis of a statistical analysis of more than 25,000 polls in 171 electoral cycles in 22 countries. The details of our analysis can be found in the research note (also see our additional analyses and replication materials), but in short we look at whether the support for government parties in polls follows the expected ‘electoral cycle effect’ – and in which situations they are the most likely to do. These are our main findings:

Government parties lose support quickly and barely recover

The average government party should not expect a ‘honeymoon’ bounce in the opinion polls: their support quickly decreases. Mid-way through the electoral cycle, the average governing party loses more than four percentage points of support. Contrary to our expectations, we see hardly any gains for government parties in the last part of the electoral cycle.

Figure 1: The electoral cycle

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying research note.

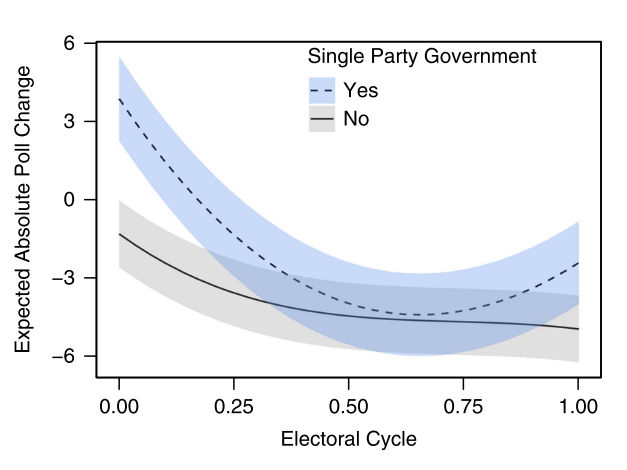

The electoral cycle effect is the strongest under single party government

If we look at the circumstances in which the described electoral cycle effect is strongest, we find that one-party governments follow the expected pattern much more closely. On average, they do have some gains early on, lose support thereafter and recover from these losses in the last quarter of the cycle.

Figure 2: The electoral cycle under one-party governments

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying research note.

Parties in multiparty governments, however, should not expect any recovery at all: they lose support during the cycle and cannot bounce back in the run-up to the next election. Of course, these findings present averages: there are always government parties, also in coalitions, which manage to win towards the end of the cycle, but on average they fare quite poorly.

In recent decades, government parties have not regained early losses

We see only a limited recovery by government parties at the end of an electoral cycle, but in recent decades this partial recovery seems to have disappeared completely. If we break down our analysis by decade, a clear ‘u-form’ can be seen in the 1960s, 1980s and 1990s as we originally expected. In more recent decades, the average governing party loses, but does not recover in the run-up to subsequent elections.

Figure 3: The electoral cycle by decade (click to enlarge)

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying research note.

Some government parties still manage to win back voter support shortly before the next elections, but that appears to be increasingly difficult. From a democratic perspective, this development can be seen as a cause for concern: if the electoral price of governing rises, it becomes less and less attractive to take on government responsibility.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying research note in Political Science Research and Methods

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Stefan Müller – Trinity College Dublin

Stefan Müller – Trinity College Dublin

Stefan Müller is a PhD Candidate in Political Science at Trinity College Dublin and holds a Government of Ireland Postgraduate Scholarship from the Irish Research Council. Starting in January 2019 he will be a researcher in the Department of Political Science at the University of Zurich. His work focuses on the fulfilment of election pledges, parties, public opinion, legislative behaviour and political text analysis. His has been published or is forthcoming in Political Science Research and Methods, Electoral Studies, the Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, the International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, and the Journal of Open Source Software.

Tom Louwerse – Leiden University

Tom Louwerse – Leiden University

Tom Louwerse is Assistant Professor in Political Science at the Department of Political Science, Leiden University, the Netherlands. His research interests include political representation, parliamentary politics, voting advice applications and political parties. He has published in various international journals, including Acta Politica, Electoral Studies, The Journal of Legislative Studies, Parliamentary Affairs, Party Politics, Political Science Research and Methods, Political Studies, and West European Politics.