Political parties are increasingly confronted with high levels of electoral volatility. Nick Martin, Sarah de Lange and Wouter van der Brug write, however, that even in times of increased volatility, connections between party elites and organised civil society matter electorally. Drawing on a new study, they illustrate how these ties can help to stabilise the electorates of parties on both the left and right.

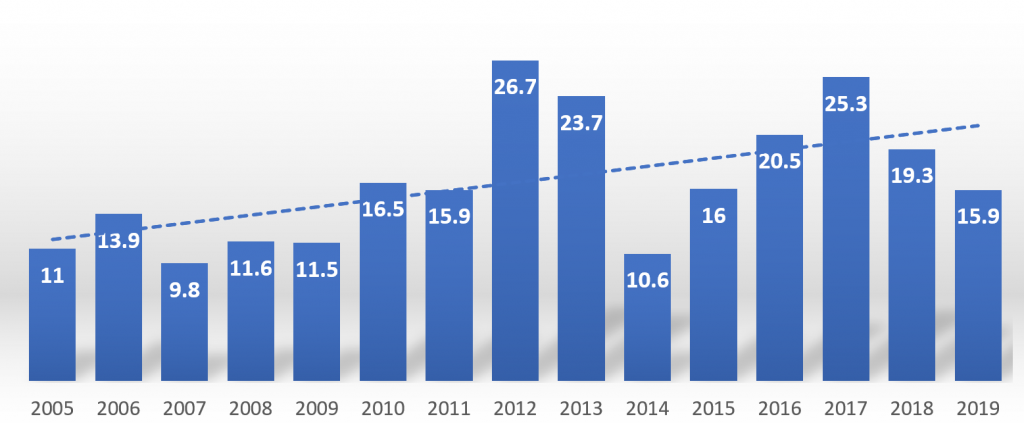

Political parties are increasingly confronted with high levels of electoral volatility (see Figure 1). Since the 1970s volatility has been rising, leading Vincenzo Emanuele to characterise the 2010s as the most electorally volatile on record. However, some parties have a more volatile support base than others. The Dutch social democratic PvdA, for example, gained 12 percentage points in 2003, but lost 19 percentage points in 2017. Other (social democratic) parties experience far greater stability, with fewer of their voters switching to or from other parties. What explains these differences between parties?

Figure 1: Total electoral volatility in western Europe (2005-2019)

Source: Compiled by the authors.

In a recent study, we set out to answer this question by building on the seminal work of Stefano Bartolini and Peter Mair. They argue that parties with stronger ties to society, a phenomenon they define as organisational density, are better able to bond voters, thereby limiting their availability to competitors. Although Bartolini and Mair examine whether organisational density affects party system volatility (i.e. the total number of votes and/or seats that change between parties at an election), they do not investigate whether it also accounts for party volatility (i.e. the absolute change in individual parties’ vote and/or seat percentage at an election).

Exploring whether parties with stronger links to societal organisations experience lower levels of volatility is important, given that volatility and party-society ties vary not only between party systems, but also between parties. Moreover, the availability of datasets on party organisation, such as the Political Parties Database and PAIRDEM, make it possible to study the relationships between parties and civil society using quantitative methods. Hence it is now possible to estimate the relative weight of party-society ties when accounting for party volatility, and comparing its importance to that of other factors, such as ideology and party size.

Parties’ connective density

There are three ways in which connections to civil society may impact on parties’ electoral fortunes. First, connections sustain values shared by parties and groups of voters. Second, connections play a part in mobilising voters on election issues salient to membership groups in civil society. And third, connections may have tangible benefits for social groups such as state funding which further cement voter loyalty. On the basis of these considerations, we suggest that parties with stronger links to civil society are more likely to be stable at the ballot box.

To explore the relationship between parties and civil society, we draw on a new dataset on party candidates provided by the Comparative Candidates Survey (CCS). We develop a measure of party-society connections, which we call a parties’ connective density. This describes election candidate memberships of civil society organisations that are active in what Steffen Blings has called programmatic mobilisation around elections. We expect that the connective density of parties plays a role in stabilising parties’ electoral support, alongside traditional links between parties and society, for example in the form of trade union and party membership. To test our expectations, we analysed data from the CCS on 149 parties at 29 elections between 2005 and 2017 in 14 countries in western Europe.

We find that party membership no longer plays a role in stabilising party support. Even though members of parties probably remain loyal at election time, their numbers have become too small to reduce volatility. Second, the connections of party elites to civil society do play a role in stabilising parties’ electoral support. The more memberships that party candidates have of organisations in civil society the more stable their parties’ support base. Parties whose elites disconnect from civil society pay a price in greater electoral uncertainty for doing so. Third, we find that the effect of parties’ connective density on the stability of their support holds for parties of both the left and the right. Though left-wing party elites are more connected to trade unions and organisations campaigning for civil rights, and right-wing party elites are more connected to business associations and religious groups, the effect of connections on electoral stability is the same.

The connected party of the 21st century

The most important implication of our study is that voters’ and party elites’ membership of civil society organisations matters electorally. Connections to civil society provide pathways for parties to large numbers of voters. Party elites who withdraw from the life of civil society risk more tenuous voter loyalty. In tight elections this can make all the difference to securing the votes necessary to win office or to pass the threshold for representation in parliament.

Parties’ ties to civil society thus help sustain their resilience. Rather than abandoning the arena in which parties and citizens interact, which Peter Mair called the ‘zone of engagement’, parties have strategic incentives to expand that zone. Our analysis suggests that the ways in which parties seek to connect meaningfully with voters is as important now as it was in the age of the mass party. The ‘connected’ political party of the 20th century characterised by large membership, formal organisational ties, and the party newspaper may have declined in significance. However, the evolving characteristics of the newly connected party of the 21st century are critical to our understanding of party competition. Hence, follow-up research should examine competing explanations for differences in the strength of party-society ties in western Europe, including those suggested by the still influential cartel party thesis.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper at Party Politics

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Shutterstock