Several UK employers and business representatives have expressed concern that the UK’s exit from the European Union could damage the country’s ability to attract skilled workers from the rest of the EU. Matthias Busse and Mikkel Barslund use LinkedIn data to examine whether these concerns are justified. They find support for the view that Brexit has reduced the attractiveness of the UK for recent high-skilled graduates from the EU, but it is far from clear whether the magnitude of this decline will have a significant lasting effect on the UK economy.

Several UK employers and business representatives have expressed concern that the UK’s exit from the European Union could damage the country’s ability to attract skilled workers from the rest of the EU. Matthias Busse and Mikkel Barslund use LinkedIn data to examine whether these concerns are justified. They find support for the view that Brexit has reduced the attractiveness of the UK for recent high-skilled graduates from the EU, but it is far from clear whether the magnitude of this decline will have a significant lasting effect on the UK economy.

Since the beginning of the year, several reports have surfaced of UK companies and employment agencies having difficulty recruiting a sufficient number of foreign (EU) workers, such as fruit-pickers and health care providers. During the referendum campaign, business representatives also stressed the importance of the EU labour pool for the UK economy and voiced concerns that Brexit could potentially stifle this inflow.

Brexiteers argued, however, that a key reason why the UK should leave the EU was precisely to allow the country to regain the ability to curtail the inflow of low-skilled persons from the EU. But by no means did “taking back control” mean to restrict the influx of highly-skilled talent from Europe, as their benefit to the economy was not in dispute in the political debate.

Data from the UK National Statistics Office reveal a slight overall decline in immigration from the EU27 (EU member states excluding the UK) over the last quarters of 2016 and a marked rise of emigration of EU citizens from the UK. There are several reasons why EU citizens, both low- and high-skilled, might be less inclined to seek employment in the UK in the wake of Brexit:

- The feeling of no longer being welcome in the country.

- Concerns about the performance of the UK economy, e.g. relocation of business activity to the EU27.

- Losses in (home country) purchasing power of retained earnings due to unfavourable exchange rate movements.

- Potentially restricted access to social rights in future, including, among other things, the right to long-term residency, access to social benefits, family reunification rights and the exportability of pensions claims.

The above-mentioned stories of labour shortages are concentrated in low- and medium-skill professions. Granted, some high-skilled sectors had also experienced shortages prior to the referendum and competition to recruit international talent was intense. But the question arises to what extent have high-skilled workers changed their attitude towards the UK as an attractive destination for work?

Data from the business-networking website LinkedIn may provide some answers to migration questions, just as it has done in the past (see our previous analyses here and here). LinkedIn features advertisements for job openings and it is possible to track the number of persons living in the EU, for example, who have browsed through UK vacancies on its website. Figure 1 shows the share of those adverts that EU27 citizens clicked on which were from the UK, as a share of all clicked on ads (domestic job listings are excluded from this calculation). We only looked at the behaviour of recent graduates – that is, individuals who had graduated within the previous year – from the EU27 since they are more likely to be willing to move across borders to find a job, and because they are likely to be on LinkedIn.

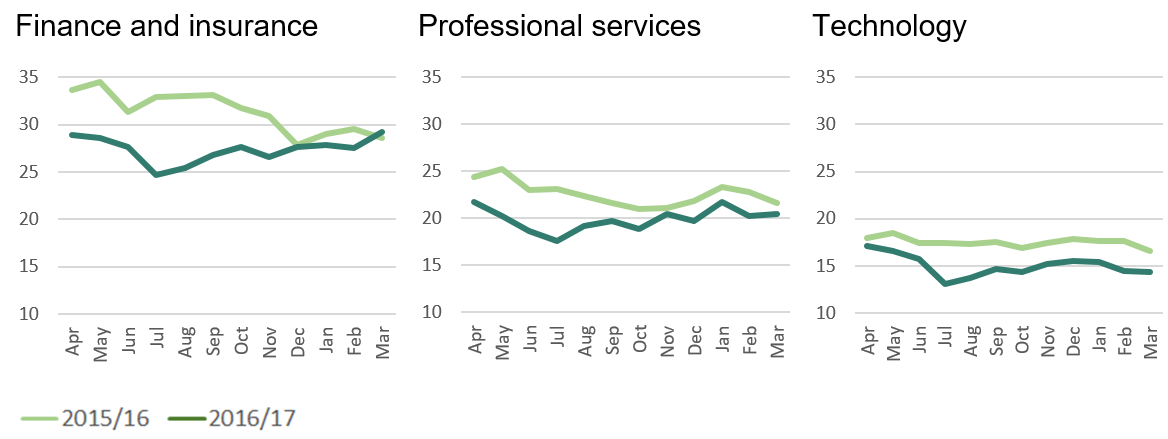

Figure 1: Clicked UK vacancy ads on LinkedIn as a share of all ads clicked on by recent EU graduates, 2015-16 vs 2016-17 (%)

Source: Authors’ own calculations based on LinkedIn data

For example, in April 2015 (light green line), 23% of the job ads which recent EU graduates clicked on were from listings from the UK. To avoid seasonal effects, we compare months of 2016-17 with 2015-16 (April to March). One can see that all points in 2017 are below the previous year. In other words, there is a general decline in the UK’s share which started even before the Brexit shock hit.

What is striking is the stark dip in searches just around the referendum on 23 June 2016. Between May and July, the share of UK clicks in all clicked ads dropped by 16%. However, the subsequent recovery suggests that this was largely a temporary effect, likely due to the high uncertainty of what Brexit means for EU nationals in the UK, for EU newcomers and for the economy as a whole. After the Brexit shock had been digested, the share of UK job ads rose back to the grey dashed line which signifies the level that one would obtain if the growth rates of the previous year are applied. Thus by spring 2017, the share is back on trend and there is little evidence that recent graduates have been permanently put-off by the prospect of the UK leaving the EU.

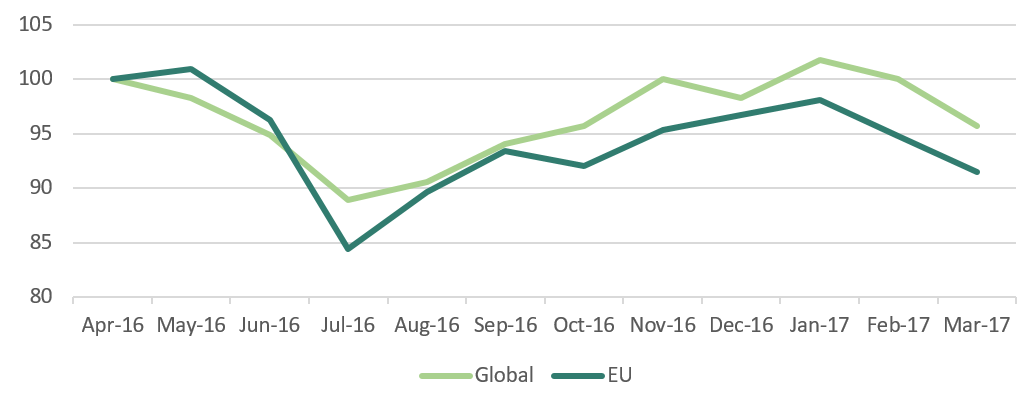

Moreover, looking into specific sectors where the competitiveness of the UK post-Brexit had been of particular concern, interest in UK job ads also bounced back. For the financial and insurance sectors, in particular, a higher share of searches was recorded in the spring of 2017 than in the previous year around the same time (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Share of UK ads in all clicked ads, searches by recent EU graduates of UK ads, by sector, 2015-16 vs 2016-17

Source: Authors’ own calculations based on LinkedIn data

Of course, not all of these movements are necessarily driven by the behaviour of job-seekers since they can also reflect a demand-side effect. Businesses in the UK might have been concerned about the rising administrative burden associated with foreign hires, the general uncertainty of what Brexit will mean for them, exchange rate volatility for exporting firms or even fear of an impending recession. These prospects may have brought recruitment to a temporary halt, thereby causing the share of UK adverts listed among global listings to decline. In LinkedIn data, this could show up as a relative decline in UK ad clicks, simply because there are fewer UK ads posted online. Aside from this demand-side effect, the counterfactual development in clicks on UK ads may have evolved differently than the trend in the past, due to other factors.

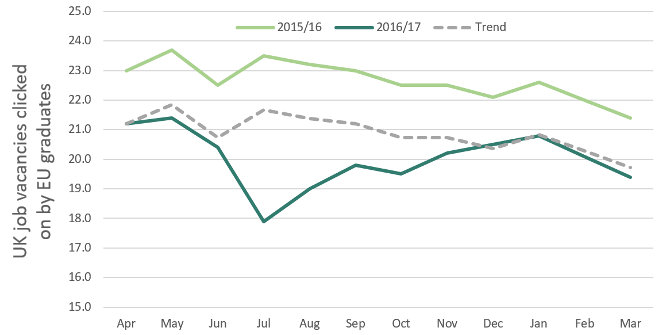

One way to address these issues is to compare the development in job-seeking behaviour of EU and non-EU graduates. The recovery in job interest since the referendum has been more pronounced for non-EU than EU jobseekers (Figure 3). This points to a small permanent impact on high-skilled EU citizens’ interest in UK-based jobs following the Brexit vote. While this comparison is not perfect, since non-EU citizens’ rights are affected by Brexit too – not least the possibility of moving to the continent at a later stage – it does provide some indication of the decline in attractiveness of the UK.

Figure 3: Trends in the share of UK job ads clicked on by recent graduates (EU and global), April 2016-May 2017

Source: Authors’ own calculations based on LinkedIn data

Our interpretation of LinkedIn data supports the view that Brexit has reduced the attractiveness of the UK for recent high-skilled graduates from the EU. It is far from clear, however, that the magnitude of this decline is sufficiently great to significantly affect the UK’s ability to recruit high-skilled individuals or to have a large impact on the aggregate real economy. Of course, this does not change the fact that for individuals directly affected by the Brexit negotiations – whether UK or non-UK citizens – a swift agreement on the future arrangement of mutual rights would allow for more certainty to plan their future, whether in or out of the EU.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Matthias Busse – Centre for European Policy Studies

Matthias Busse – Centre for European Policy Studies

Matthias Busse is a Researcher in Economy and Finance at the Centre for European Policy Studies.

–

Mikkel Barslund – Centre for European Policy Studies

Mikkel Barslund – Centre for European Policy Studies

Mikkel Barslund is Research Fellow in Economy and Finance at the Centre for European Policy Studies.

“by no means did “taking back control” mean to restrict the influx of highly-skilled talent from Europe, as their benefit to the economy was not in dispute in the political debate. “

And

“Brexiteers argued ….. to regain the ability to curtail the inflow of low-skilled persons from the EU “

Absolutely – both.

But neither statement supports the headline – “EU talent is being chased away by Brexit”

If EU “talent” has felt discouraged about the UK, one needs to ask why.

It certainly wasn’t from what Leave campaigners actually said.

But it was irresponsible of people like Nick Clegg and Vince Cable to characterise leaving the EU as “pulling up the drawbridge” – with commentators magnifying this theme.

Constantly bringing up “EU citizens rights in the UK” didn’t help” either – as it fed an impression that their “rights” were under threat – when they weren’t.

The only threat to “EU talent in the UK” is from EU intransigence:

– refusing to reassure UK ciitzens in the UK

– blocking “passporting”, mutual recognition of professional qualifications

– preventing “business as usual” re: free trade

As a highly qualified EU citizen who also holds British citizenship, I can tell you that the rhetoric has put off many EU citizens and the UK is sadly no longer an attractive destination.

The show of xenophobia we’ve witnessed since last year is an absolute disgrace.

…and even if the UK is an attractive destination, not because of the superiority of British business but because of the globalised dimension in which this business is growing, the recruiters, the recruitment managers and the gatekeepers to access the job market are absolutely repugnant to such an extent that it could be called out extreme discrimination on the basis of our EU background.

Most EU talent has been internally relocated with the help of the global companies. Global business and global trade has the same principles…Not in the UK. The UK market expects someone to reset your career history and trivialise the importance of educational background (even if it was gained at the LSE…) by arguing that you are not tested in UK waters…as if the UK private sector is an asset to someone’s career history.

The companies don’t understand that there are EU citizens that are career-driven. They treat us as we owe them a favour by giving us opportunities that are not commensurate with our skills, abilities and most importantly with our work experience.

Exactly because this vicious circle goes on and on, that is why EU talent is actually kicked out from the UK blatantly but of course in the typical process-driven subtle way.

Brexit is the cultural perception gap that is reflected not only in political and ideology-driven terms but most importantly in day-to-day social interactions.

“If EU “talent” has felt discouraged about the UK, one needs to ask why.

It certainly wasn’t from what Leave campaigners actually said.”

They ran a campaign that said European immigrants were pushing down wages, making life more expensive for natives, pushing up unemployment (and that more people were coming including millions of Muslims). That is saying that EU immigrants are making your life worse and we only get a better life by getting rid of (some) of them.

Some people then went on and attacked or intimidated EU immigrants, which I don’t blame Leave campaigners for, but it happened because of these debates. EU immigrants also now, just because of Brexit, don’t know what their status is in the country. We are also promised that we’ll have a points based visa system (and the only point in a points based visa system is to make it so that some people “fail the test” and don’t get a visa). Obviously that is making people feel less welcome. We are not even discussing here the undertone to the campaign – deep dislike toward immigration, talking all the time about foreigners telling us natives what to do, need I go on.

But you ask why some people feel discouraged about staying in the UK? Go and talk to some of us and see how we feel. It’s very clear. You wouldn’t feel welcome either if you were an immigrant in a country that behaved this way towards you. I am sorry if this sounds emotional but I cannot see how someone could be so out of touch as this.

MN,

I was very careful to copy the article’s HEADLINE which referred to “EU talent”

The Leave issues included;

– large scale migration

– low paid migrants – not “talent”

– wage compression – which is more keenly felt at or near Minimum Wage

“making life more expensive for natives”

Absolutely.

House prices have gone up 5 fold in 24 years. RPI “just” double. So millions of extra people have made housing more expensive (regardless of where they are from).

No Leave campaigner ever said “get rid of” migrants who are already here.

“EU immigrants …., don’t know what their status is in the country”

Perhaps – but only because the EU refuses to protect UK citizens already in the EU.

The UK Govt. (and Leave campaigners) made it clear that those here were welcome to stay.

So any EU people worried should lobby the EU to get on with agreeing reciprocal arrangements.

There is very, very little “deep dislike toward immigration” of “foreigners” – as individuals.

The British travel outside their country way more than (say) the French.

The issue is …. too many SETTLING in a short period of time – and the impacts on house prices, school places, health clinics, transport.

If you (and others) feel “discouraged” – address your complaints to the broadcasters who kept stirring.

They have persistently fuelled “doubt” – despite repeated assurances before and after the Referendum.

“I was very careful to copy the article’s HEADLINE which referred to “EU talent””

Actually you didn’t. The headline is a question, you copied it as a statement saying “EU talent is being chased away by Brexit”. There was nothing careful about that – you completely misrepresented the article by doing so.

More to the point, it’s flat out astonishing that you can’t see why EU migrants would be discouraged from coming to the UK. The Leave campaign consistently, over and over again, hammered the idea that EU immigration was the root cause of hardship for the native population. We had a 41% hate crime rise right after the vote according to Home Office figures. We had Vote Leave publishing lists of EU criminals that they alleged we couldn’t deport because of the EU. We had a consistent (and illogical) conflating of EU migration with Islamic migration and all the Islamophobic rhetoric that goes along with that line of argument. We had senior campaigners like Iain Duncan Smith claiming that the UK would be more likely to experience Paris style terrorist attacks if it stayed in the EU because EU migrants were more likely to be terrorists. We had Farage and his Breaking Point poster. It was hysterical campaigning designed to inflame tensions over EU immigration. It’s to the surprise of nobody that EU migrants saw that and now would rather take their chances in a country that doesn’t have such a monumentally negative discourse around their presence there.

That’s just the campaign, on the policy side we now have an explicit commitment to reduce the rights of EU citizens and make it harder for EU workers to come and live in the UK (they can do it without a visa today, in future they’ll need to have a visa or jump through some other administrative hoop to do so – the government refuses to say anything specific on this point a year after the vote, leaving migrants completely clueless). Then we have the straightforward gaffes, like the Home Office sending EU migrants letters indicating they were about to be deported. Or we have the indirect effects like the fact that Brexit tanked the pound and ensured wages in the UK are now worth substantially less relative to the euro than they were before the vote. Or the fact that there’s a huge degree of uncertainty now hanging over parts of the workforce directly because of Brexit. Or the fact the UK’s image has taken a pounding on the continent.

You can argue all of this is justified if you like, but how on earth can you argue that the UK is likely to be just as attractive to EU migrants after all of this? You’d need to be living under a rock to think that’s actually the case. You can go to France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands or another EU country and face none of this baggage.

Magdalena: All I will say is that I hope you can still see there are plenty of people in the UK who want EU citizens to be here, that the result of the referendum was close, and that the anti-immigration campaigners aren’t a majority. I hope people like you will stay in our country and continue to make it a better place to live in.